Waterloo Teeth | The Truth About Wearing Deadmen’s Teeth

This post is dedicated to a by-product that not only came from a battlefield that shares the same name, but also a product that gave the body snatchers a very lucrative sideline.

What am I talking about? Well, Waterloo Teeth, also known as dead men’s teeth of course!

With the consumption of sugar fast becoming a favourite pastime for the upper classes of Georgian Britain, this excessively sugary diet soon changed the once ‘white’ teeth of our ancestors to black stumps of rotting enamel.

Tooth extraction, although painful, was common enough for people to start removing these little old stumps and replacing them with something that would perhaps be a little less smelly and er, black.

But what exactly did people do if they needed to wear false teeth or dentures in the 1800s?

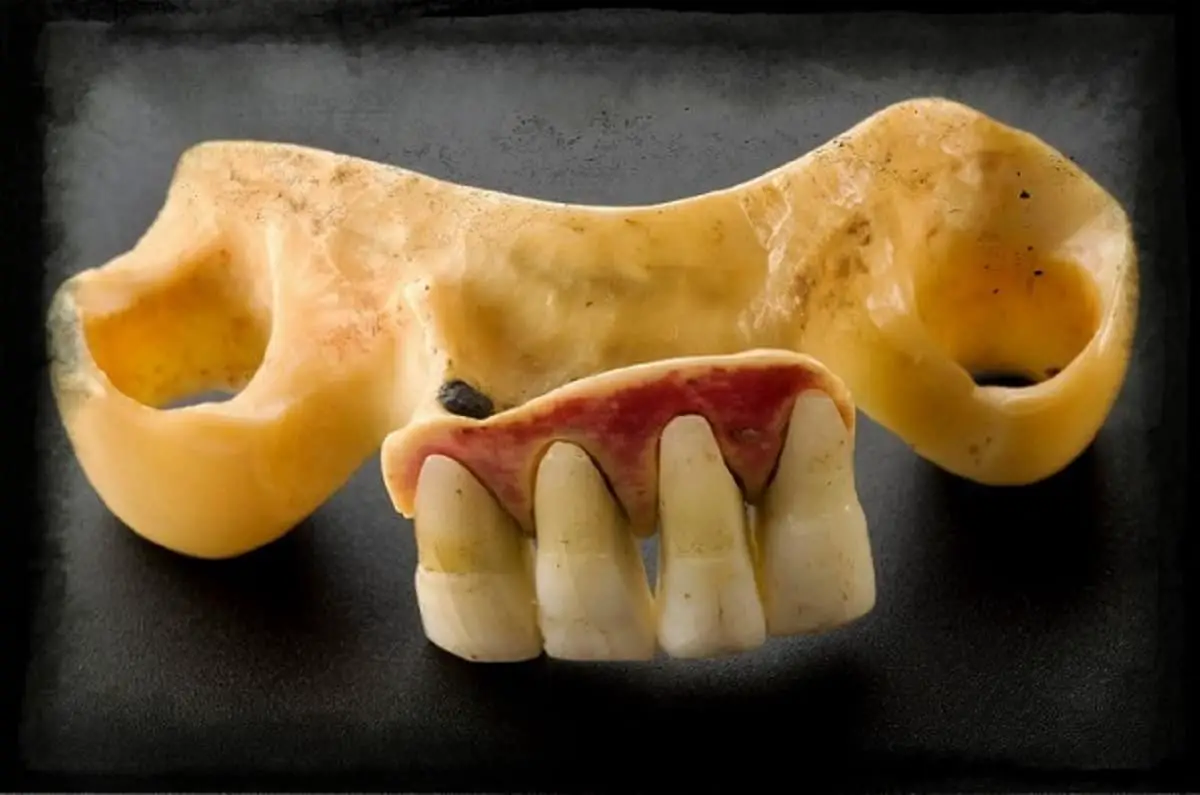

Human teeth, either derived directly from pauper’s mouths or extracted from cadavers by body snatchers, made up a high proportion of false teeth worn in the 19th Century. In 1815, a vast majority of human teeth in dentures had been also removed from dead soldiers on the battlefields of Waterloo. Better known as ‘Waterloo Teeth’, these would be cleaned, scraped, drilled and mounted onto an ivory base before being inserted into the mouths of our ancestors.

Not only would these dentures have been incredibly bulky to wear, but the chances of being able to eat a proper meal with them in place was probably minimal. I personally would have tried quitting sugar, but then I didn’t live in Georgian Britain.

What Are Waterloo Teeth?

The craze in using human teeth to replace rotting stumps in our ancestors’ mouths was a trend rapidly growing in Britain by the 1800s.

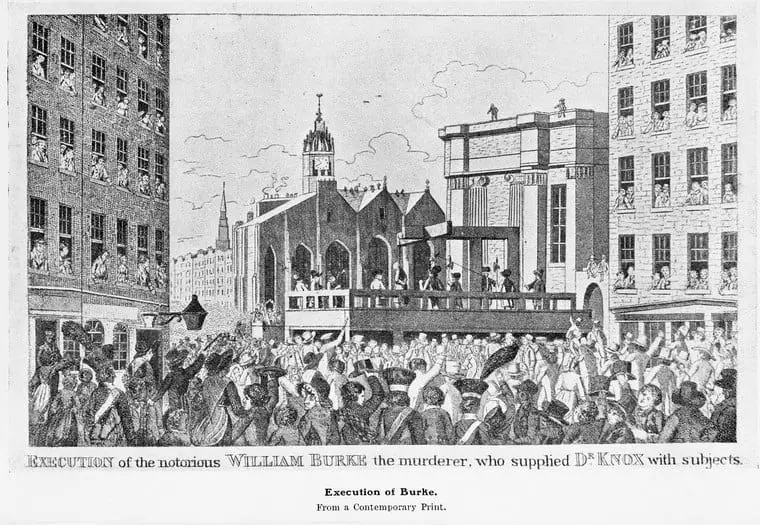

Waterloo Teeth is the name given to the teeth that were extracted from soldiers who lay dead or dying on the battlefields of Waterloo in Belgian in 1815. These teeth would then be made into dentures and sold to the upper classes of Georgian Society.

Ruthless men such as body snatcher Tom Butler, a member of the notorious Borough Gang (which you can read more about in my blog post here), must have seen countless opportunities to make money from the 30,000 dead strewn across the battlefields at Waterloo.

On arriving in France he presented himself to Brandsby Cooper, nephew to eminent anatomist and surgeon Sir Astley Paston Cooper.

When asked the reason for his visit he said ‘for teeth’ and then delivered one of the most famous lines a body snatcher may ever have muttered:

Oh, Sir, only let there be a battle, and there’ll be no want of teeth. I’ll draw them as fast as the men are knocked down.

He must have delighted in picking his way over the corpses, extracting as many teeth as he could lay his hands on.

…the battlefield quiet in the half-light, the deadly perfume of blood and gunpowder hanging over the broken remains of men and horses, and the jackal figure moving stealthily from one body to the next, pincers in hand, open haversack at his side, wrenching and twisting, then passing on, leaving each set, tortured face with a wider, bloodier grin than before

Hubert Cole: Things for the Surgeon

Such was Butler’s success at the battle of Waterloo, that it is said he made £300 on one trip (nearly £14,000 in today’s money) and that he was able to set himself up as a dentist in Liverpool, only to succumb to the lures of the demon drink gin and lose everything.

We also know that one of Butler’s fellow gang members, a body snatcher named Harnett, is reputed to have made £700 from a trip to France collecting teeth. Although he did have the misfortune of leaving the teeth in the care of his daughter who in turn left them in a coach, only for another body snatcher to eventually put his hands on them.

For a fantastic insight into the world of Waterloo Teeth and the development of dentures and dentistry, I thoroughly recommend watching this YouTube video ‘Dentures and Dentistry: An Oral History.

The whole programme is fascinating, but if you just want to watch the bits about Waterloo Teeth, then fast forward to 10:50.

What Were Dentures Made of in the 1800s?

Before the idea of using human teeth was dreamt up, dentures in the 1800s were extremely rudimentary affairs.

Bulky, unyielding and prone to staining, these first forays into artificial teeth were not only expensive but also sounded more cumbersome than they were worth.

Bone, ivory and even animal teeth would have been used to give our ancestors a wider grin. Set into a base crafted from ivory, you can imagine how uncomfortable they would have been to wear, the hard base rubbing on sore gums.

The two halves of the base would have been held together with brass piano springs. The tension created when clamping the two halves together was used to hold the teeth in place. I can only imagine how many unfortunate sets were displaced across the room at some sudden outburst of laughter!

Although most teeth would have been crafted in this way, the curator of the British Dental Association, Rachel Bairsto noted in an interview on the subject with the BBC, that the use of human teeth in dentures can be traced back even as early as 1792.

The most famous false teeth are those of American President George Washington. The bulky teeth often referred to as being made of wood, were in fact made from ivory, as well as gold and lead I understand. The wood ‘myth’ apparently being misinterpreted over the years due to the build-up of stain on the ivory.

Selling Your Teeth In the 1800s

But not all teeth came from the dead. Before 1815, the source of human teeth, besides coming from cadavers, would also come from living ‘volunteers’.

The illustrator Thomas Rowlandson in the image shown, the same man who has given us so many drawings relating to body snatching, also furnished the reader with horrifying images of tooth pulling.

In this image, the donor, a chimney sweep, doesn’t look too horrified at the prospect of having his teeth pulled. Why you can even see others walking out of the door clutching their mouths and looking at the money they’ve just made nestling in the palm of their hands.

In comparison, the realisation of the female recipient on the left of what is about to happen gives a little more cause for concern.

The poorer members of the parish were well known to have stood in line at the dentists so that their ‘two front teeth’ could be extracted and inserted into the waiting mouth of a Georgian aristocrat.

If you’ve ever watched the musical ‘Les Mis’ you’ll know that Fantine sold her two front teeth out of desperation to support her daughter. So horrific was the scene from the BBC adaptation in 2018, that people were even commenting on Twitter!

Why not take a look at this clip via The Sun Newspaper and judge for yourself.

Pulling the teeth from paupers was a real thing and could earn them good money for food, bed and quite probably a wee nip of something to take away the pain.

How Did They Remove Teeth From Cadavers?

We’ve all heard of the horror stories of early dentistry, where jaw bones were pulled out along with teeth.

But although the history of dentistry is interesting, I’m more intrigued as to how the dentists got the teeth in the first place, this is a blog about body snatching after all!

There was certainly no finesse when it came to a corpse and the desire to take its teeth.

Every good body snatcher knew that the teeth had to be removed almost immediately after snatching a corpse.

If you were caught with the goods in tow, you could ditch the cadaver and make a run for it – the teeth safely secured in your coat pocket. That way, it wouldn’t be a wasted night.

Body snatchers would use either the blunt end of the spade handle or more commonly a brawdle, whacked against the jawline with the tooth prised and gouged with the additional help of some pincers.

The jaw wasn’t really needed after all, unless it was of particular interest, and if the teeth were in good enough condition to sell on, then the price was worth it.

The Italian Boy

When body snatcher and murderer James May was questioned in the dock in 1831 over his involvement in the murder of an Italian Boy, thought to be Carlo Ferrier, he openly admitted to removing the teeth and selling them on:

I used a brad awl (sic) to extract the teeth from the boy, and that was the regular way of business, and in doing so, I wounded my hand slightly…

Such was the force of removing the Italian Boy’s teeth, that May actually chipped one of the front teeth.

The best thing about the teeth in this case, and which Wise describes so brilliantly in ‘The Italian Boy’ is the description of May at the premises of dentist Thomas Mills.

Looking for a sale, May presents Ferrier’s teeth to the dentist, all 12 of them, with gums and jaw bone still attached! It’s awful to say but it’s details like this that keep me researching body snatchers!

In fact, if you read Ruth Richardson’s notes on the murder in her acclaimed book ‘Death, Dissection And The Destitute’, available here via Amazon, she gives a great link to a report in the York Chronicle where Ferrier’s teeth were actually displayed in a shop window in the ‘Borough’ and eventually sold for 12s. 6d.

Patrick Murphy’s Venture Into A Crypt

When it comes to teeth the Borough Gang really did go all out.

So much was the reward for stealing teeth that bodies were even dug up for their teeth alone.

Partick Murphy, one-time leader of this notorious London gang, was even more ruthless than Ben Crouch the original patriarch, took it upon himself to try to extract some teeth from a vault. Realising this was an ‘untapped’ source, he played one of his best cards to date.

Upon visiting the burial ground, ‘his eyes reddened from tears’, and he expressed a wish that his recently deceased wife should be laid to rest in a ‘neat and quiet sanctuary’. The fact that the burial vault had nothing to do with his or ‘his wife’s’ family had nothing to do with it.

A slight sweetener of half a crown slipped into the hand of the superintendent of the chosen burial ground appeared to do the trick and he was let into the burial vault to choose a suitable resting place for his dearly beloved.

During his inspection, he managed to tamper with the vault door thus enabling him to gain access undisturbed later that evening. Such was Butler’s cunning ways that he netted himself £60 from this one raid alone!

Prices For Human Teeth in the 1800s

If there wasn’t a profit in extracting teeth and selling them separately to the dentists, then, believe me, the body snatchers wouldn’t have done it.

I’ve already mentioned some of the eye-watering amounts that could be made from the battlefields at Waterloo, but everyday dealings in teeth could prove just as lucrative and the demand for human teeth in the dentures of the rich was starting to drive prices for this commodity through the roof.

In 1830, renowned body snatcher Thomas Goslin, aka Thomas Vaughan, one time member of London’s Borough Gang, messed up and he messed up big time.

He’d got sloppy in his habits where body snatching was concerned. He was arrested and tried for having, among other things, grave clothes in his possession and for stealing two corpses from the graveyard at Stoke Damerel, Devonport (to cut a very long life story short).

When officers searched his house, they found over 100 teeth on a washstand, cleaned and ready to sell to the highest bidder.

After sentencing, for which Goslin and his associates were eventually transported for 7 years, Goslin had the cheek to ask if he could have the teeth back! Naturally, his request was declined.

One of the men Goslin lured into his grave robbing ways was Nicholas Wood, a gravedigger from the church at Stoke Damerel.

Wood claimed that Goslin had persuaded him into letting him have some teeth from the corpses buried within the churchyard and stupidly he agreed but instead pleaded with him:

For God’s sake, don’t meddle with the bodies

Wood was given various gifts of thanks from Goslin to show his appreciation. On one occasion he received ‘as much as half a sovereign at a time and several times a shilling or two’.

Finally, after gentle questioning, he admitted to receiving thirty shillings for the teeth that he’d let Goslin remove from the corpses, a week’s wages for a skilled tradesman in 1830.

A tempting offer to say the least and one which Goslin would easily have recouped his money on.

Body Snatcher Joseph Naples

Lots of teeth meant lots of money and this certainly must have been in the forefront of Napels mind when he turned his hand at extraction.

Gang member Joseph Naples, from the ‘famous’ Borough Gang in London had a bit of a thing for removing extremities and as a body snatcher in the know, he would remove the teeth from cadavers before they’d even left the graveyard.

In 1802 when he was arrested and sentenced to two year in Coldbath Fields prison for stealing cadavers from the burial ground at Spa Fields, Naples openly boasted that he would receive a guinea a set ‘sometimes more’ on selling teeth to the hospitals.

Naples is a really colourful character and I looked at his snatching from Spa Fields in another post of mine ‘A Short Tale Of A London Body Snatcher’ where I also looked at his brief escape from prison!

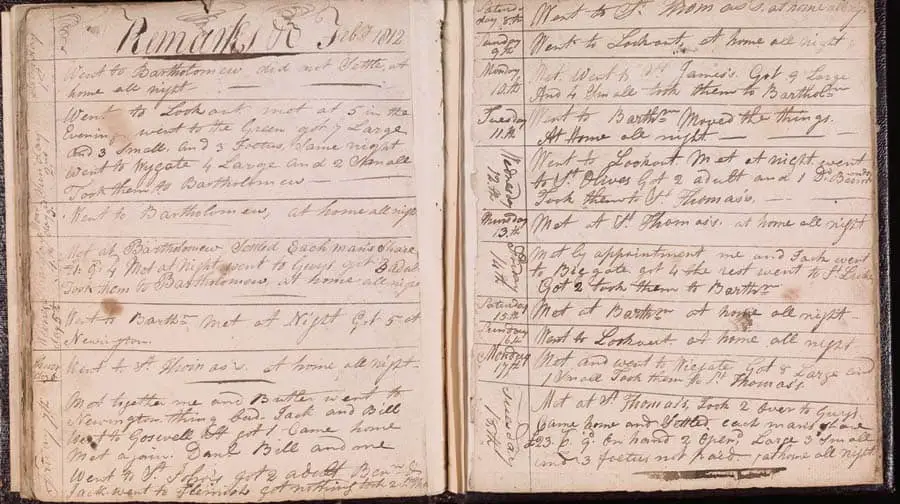

The Diary of A Resurrectionist

To help get an understanding as to how much tooth extraction was on the minds of the body snatchers as they were going about their work, we can turn to the ‘Diary Of A Resurrectionist’, a fabulous resource I’ve spoken about many time on this site and which I’ve linked to at the bottom of the post.

Scattered throughout the ‘Diary’ you’ll find a few entries referring to canines, the colloquial term used by the gang for teeth.

What’s best about the ‘Diary’ is that we can find out who the gang were selling the teeth too and for how much! Let’s join the gang in a busy November in 1812:

Tuesday 24th November

Went movd. One to Carpue, got pd. Came home met at jack at 5, Bill not home, did not go out till morning. Jack sold the Canines to Mr Thomson for 5 Guineas

Wednesday 25th November

Met Jack at 2pm. Butler myself went to B. Ln got 1 adt. Jack, Ben, Bill went Pancs. Got 5 adt. 1 small, took them to Batholw. Removed 3 to Cline, got 2 sets of cans.

There are many abbreviations here referring to other gang members, graveyards and also the anatomists that were buying the cadavers from the gang. There’s lots to take in!

Without having to complete a Masters dissertation on the ‘Diary’ you may instead like to get a quick introduction to its history and look at typical week from 1812 in my post ‘A Week In The Life of A London Body Snatcher’

The history of dentistry is a fascinating one and one which I hope I’ve been able to pique your interest in here and show how body snatchers played their part in creating the perfect smile. If you are interested in researching the topic further, then I hope you find my recommendations below of interest.

My Book Recomendations

I read some great books when reading about this topic and if you’d like to know more about certain cases I’ve mentioned then I hope you’ll like my recommendations.

The Smile Stealers By Richard Barnett

I only managed to just dip into this book but what I’ve seen looks fantastic and I have it on good authority that it’s worth buying and so I’ve put it on my wish list. The cover alone makes it look an awesome read!

You can buy Smile Stealers from Bookshop.org (UK) here.

This book is actually part of a series which also includes the book ‘The Sick Rose’ and ‘Crucial Interventions: An Illustrated Treatise on the Principles & Practice of Nineteenth-Century Surgery’ which is also available via Bookshop.org (UK)

British Dental Association Museum

For some great images of Waterloo Teeth, (and let’s face it who doesn’t love looking at teeth), as well as a really good interview with the curator of the British Dental Association Museum, Rachel Bairsto, take a read of this article here on the BBC website.

I think you’ll all be highly delighted at the images! Especially the Waterloo Teeth all strung up for sale!

The Italian Boy by Sarah Wise

For the information on James May and the Italian Boy I turned to perhaps THE best source on the case in my opinion, Sarah Wises’ ‘The Italian Body: Murder And Grave Robbery In 1830’s London’.

Wise has put a HUGE amount of research into this book and like Ruth Richarsonson’s acclaimed work ‘Death, Dissection and The Destitute’, that I linked to previously in my post, Wises’ book will certainly become the authority on this case, if it hasn’t already.

For further information on the other accounts that I’ve mentioned here, it really was a case of dipping into a number of different body snatching books that I already own and piecing together the relevant information.

Things For The Surgeon By Hubert Cole

Perhaps the most useful I found was Hubert Cole’s ‘Things For The Surgeon’. This classic work was published in 1964 and although it can be slightly tricky to get hold of, it’s an absolutely fantastic read.

It took me a while to find mine, but if you’re interested in the topic of body snatching then it’s certainly worth the hunt. I’ve found copies available on Amazon.co.uk although it was a little pricing at the time of checking.

Diary of A Resurrectionist

Finally, perhaps one of the most useful books that we have on the methods and daily transactions of the body snatchers during this period is from the ‘Diary Of A Resurrectionist’, a diary that is thought to have been kept by body snatcher Joseph Naples.

I’ve mentioned Naples’ Diary many times on my site and you can read more about him in my post ‘A Short Tale of A London Body Snatcher’ But if you want to read the Diary for yourself, you can do so for free via Project Guttenberg Website