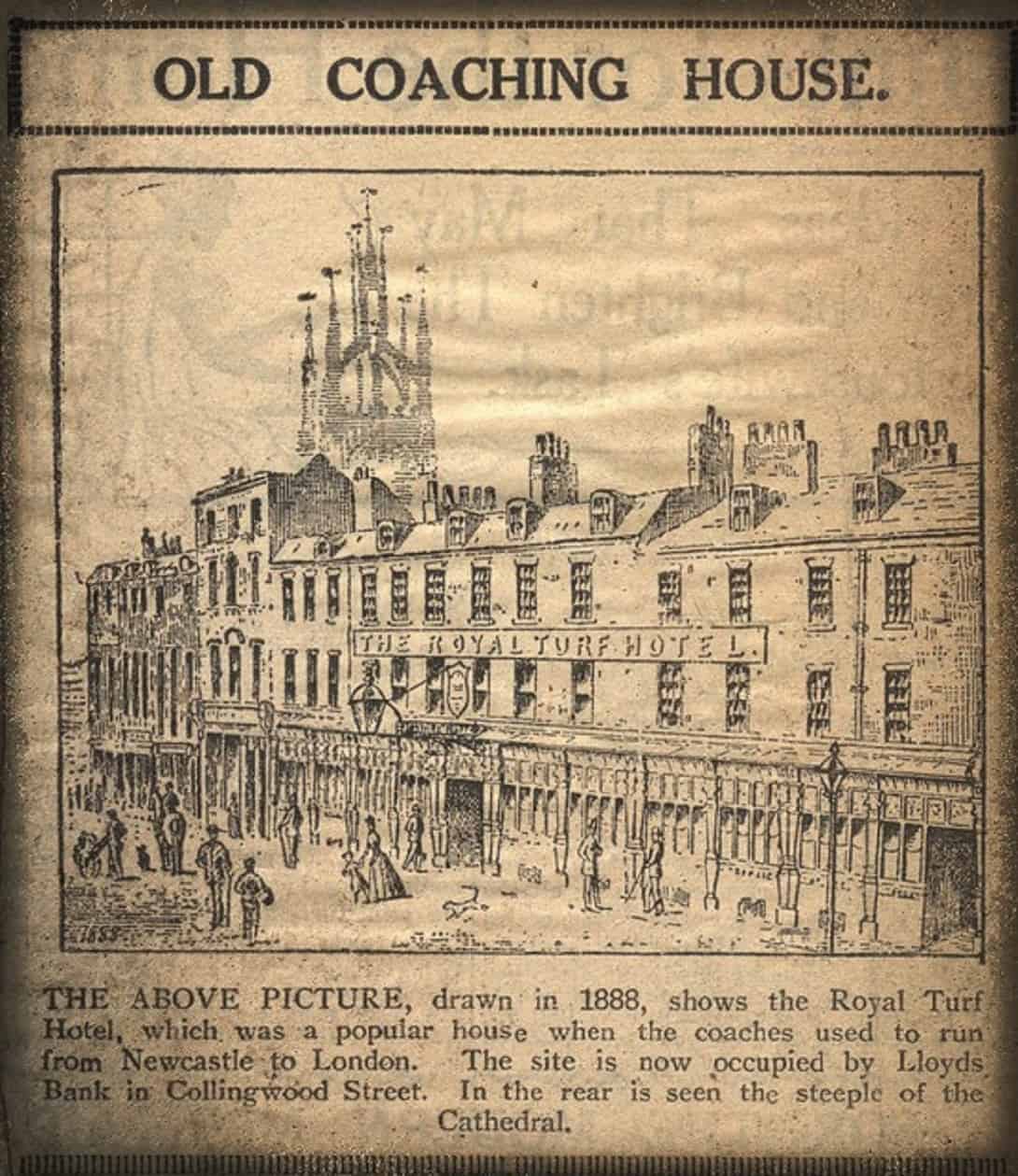

The Turf Hotel, Collingwood Street, Newcastle

Notwithstanding an already arduous journey; one that involved jostling, the consistent rumbling of wheels, and the potential threat of highwaymen, Georgian coach passengers often had to endure an altogether more unsavoury aspect to their journey.

As one of the major travel hubs of Georgian England, the Turf Hotel was a busy interchange during its day and a familiar site in Newcastle. Its yard would have been awash with a noisy clatter and gabbling people clutching their luggage hoping to travel far and wide throughout the country.

Well, as far and wide as you could in the 19th century.

Not only was there a steady succession of coaches leaving the inn throughout the day (3 to London, 2 to Edinburgh and 1 to Carlisle, Lancaster, and Leeds) but it was also touted as

[affording] ample accommodations for the passengers of one of the largest and best-regulated coach-establishments in the United Kingdom’ … [occupying] most of the south side of [Collingwood Street]… terminat[ing] in the elegant house of Mr. William Fife, surgeon

During the late 1820s however, there was rarely a time when the (Royal) Turf Hotel on Collingwood Street, one of Newcastle’s busiest thoroughfares, was out of the newspapers.

The publicity was of the type that no-one really wanted. A side that brought the underworld of Georgian Britain right into the homes of the upper classes.

The Turf Hotel’s Darker History

Thirst for medical knowledge had driven the cadaver trade to an all-time high. Demand for fresh corpses was far outstripping supply as anatomists across the country requested bodies for their anatomy lectures.

As a result, corpses would be ‘shipped in’ from the provinces. An unspoken network of correspondence occurred between the anatomy schools of Edinburgh and London and body snatchers trying their hand in the smaller provisional towns.

Requests were made by either by the surgeon directly or via their ‘usual’ resurrectionist. A body would be lifted and shipped, no questions asked.

Protecting The Dead

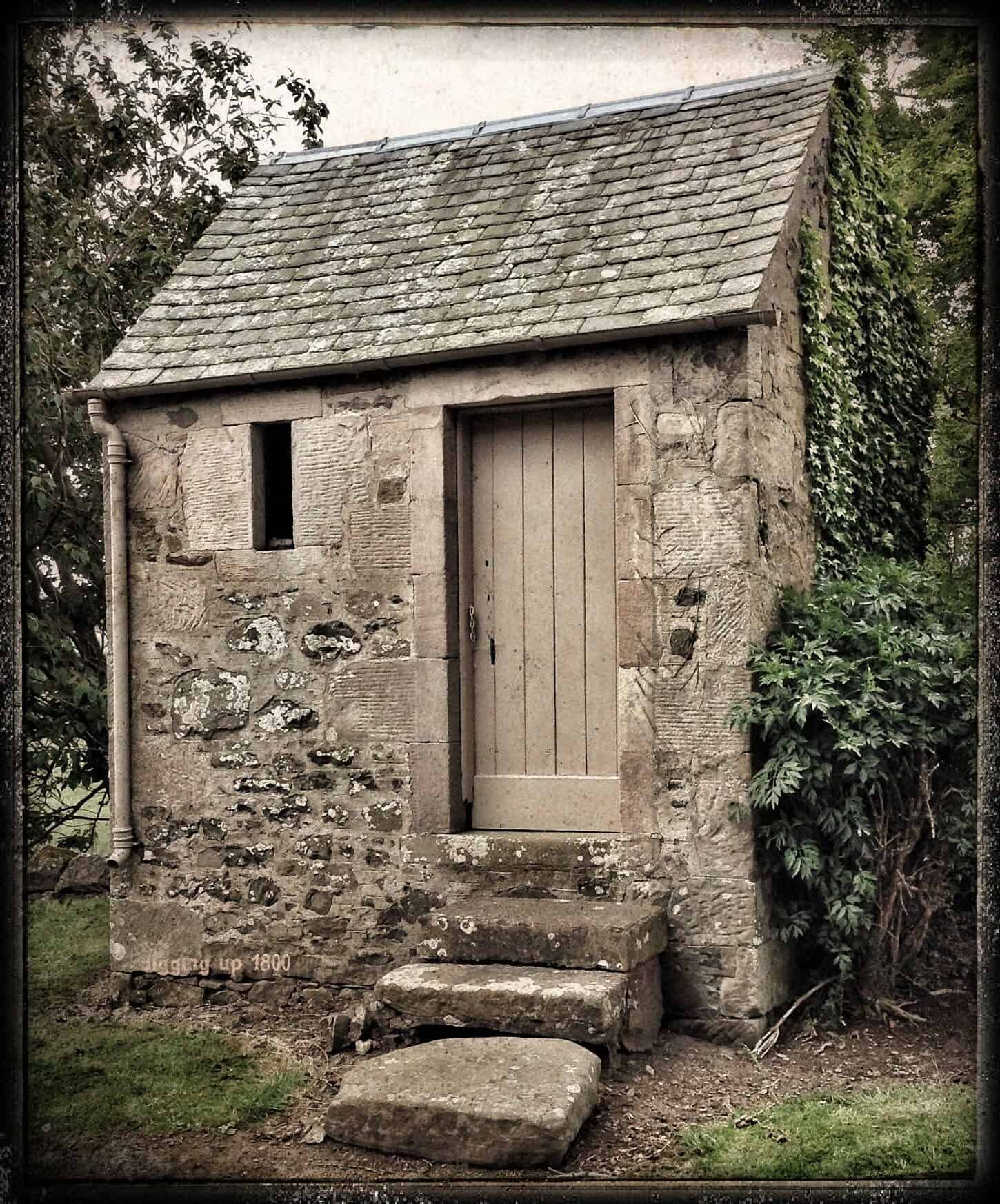

This increased demand meant that inner-city churchyards went into high alert in an attempt to thwart the body snatchers.

Watches were taken up in purpose-built ‘houses’, high walls were erected around churchyards and as you moved north away from Newcastle, caged lairs and mortsafes would become a familiar sight.

‘Handle With Care…’

Cadavers were usually placed into hampers or boxes typically measuring 25in x 16in x 16in.

Labelled as all manner of goods in an attempt to disguise their contents, this could be anything from ‘Glass. Handle With Care’ to a simple address label. Everything and anything was used.

Perhaps one of the more descriptive accounts that we have of an address label comes from an account written in the York Herald & General Advertiser Saturday, Nov 19, 1831.

The deal (pine) box in which the cadaver had been stuffed measured 2ft square and was en route from the Bull and Mouth Hotel in Leeds, having been strapped tightly to the roof of the coach.

The box was specifically addressed to ‘The Rev. Mr Geneste, Hull’ and was detailed:

By Selby Packet – To be left till called for – Nov 11. Glass, please keep this side up

A Corpse’s Journey

After jostling over England’s finest road network, and presuming the coach was on time, the tightly packed cadaver would still have suffered some damage while in the box.

One way a body would have been discovered was if liquid, or rather corpse fluid, (I refrain from using the word juice), had started oozing from the corners of the box.

Many a box was discovered when strange and noxious smells started to escape into the atmosphere and passengers began to complain about an unsavoury smell in the carriage.

The Body in the Box

In January 1826, more inquisitive staff members suspected that the large number of similar boxes passing through the Turf Hotel on their way to Edinburgh contained something a little more unsavoury than your usual luggage items.

The box in question had arrived from Leeds on the Telegraph coach during the night of the 6 January, having been dropped off at the coach office the previous day.

By the time it arrived in Newcastle, curiosity had got the better of a few individuals at the coaching inn and the box, which weighed upwards of 16 stones (224 pounds) was removed from the Telegraph and placed in the courtyard for all to see.

When they arrived on-site, the police took matters into their own hands and immediately removed the lid of the box, exposing the dead body of a recently deceased male.

After a search was made of the deceased’s grave in St John’s churchyard, Leeds, it was found that his coffin was empty and that the cadaver on its way to Edinburgh was, as his son suspected, the Late Mr Thomas Daniels (Snr).

At the April Borough Sessions in Leeds that year, and after a quick bit of detective work, George Cox, the son of a box-maker from Kirkgate in the same city was sentenced to six months imprisonment in York Castle.

Delaying A Corpse

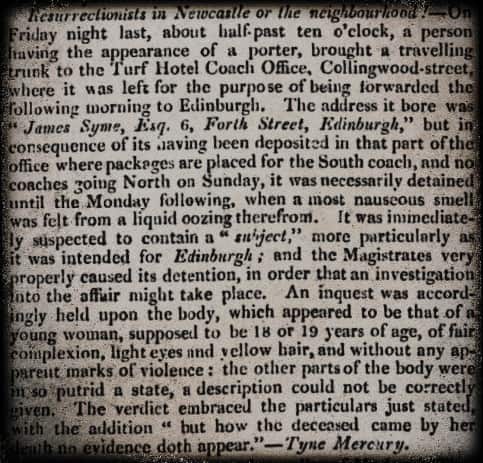

A year previous, in 1825, a most putrid scene was encountered at the Turf Hotel.

Coaches didn’t run on a Sunday, so just like today, if you missed your connection you had to wait around till the next one.

One Saturday night in September, a ‘porter’ left a travelling trunk at the offices with a wish for the trunk to be sent to Edinburgh. The next coach leaving Newcastle was heading south towards London, so the package remained in the offices until Monday morning when the coach for Edinburgh departed.

In the meantime, whether this particular September weekend had been unusually warm or whether the cadaver stuffed into the trunk was already decomposing is not known, but a small trickle of liquid began slowly oozing from a corner of the box, filling the offices with ‘a most nauseous smell’

On this occasion, the box was addressed to a James Syme, Esq. 6 Forth Street, Edinburgh.

It has been suggested that the infamous Burke and Hare used this alias to transport cadavers across the country but I was sorely under the impression that they were Edinburgh murderers so I’d take this with a pinch of salt*.

The enviable job of opening the box once again fell onto the police and this time they were greeted with the body of a young woman about 19 years of age.

Her complexion was fair, her eyes light and her hair ‘yellow’ [blond] and she had died without any ‘marks of violence’.

Like so many of the cadavers, she joined the other discoveries in Ballast Hills Burial Ground.

More Discoveries

And still, the bodies kept coming. Two cadavers were reported to have been discovered in January 1826.

One box travelling up from the south was stopped at The Turf Hotel under the suspicion that it was transporting dead bodies.

And quite rightly so, a box containing the corpse of an old woman was discovered, she again being interred at Ballast Hills.

Only 10 days before had another box been discovered. This one a male body from York, only 89 miles away, was again interred in Ballast Hills.

A double find also occurred on Tuesday 11 November 1828 when the bodies of two females were found stuffed into hampers.They weren’t found on the back of the coach but rather in the coach offices themselves.

One came from the Highflyer from York, and the other was brought by a man to be booked into Edinburgh.The lady arriving from York had originally alighted on the 8 November, but when the staff at the Turf Hotel became suspicious, they sent her back by ‘return post’.

Unfortunately, the coach office in York promptly popped her back onto the Highflyer and sent her off again in the direction of Edinburgh.

Not the best of situations.

The man however who had brought the second cadaver to the coach offices was actually apprehended, although acquitted after a brief trial.Both bodies of these unfortunate ladies were buried in St John’s Churchyard, Newcastle.

The Last Box

It is said that by the mid 19th century, so many cadavers were being discovered hitching a ride on mail coaches that Ballast Hills, the burial ground in Newcastle that was to become the final resting for many of these souls, was suffering immense overcrowding.

It is perhaps fortunate then that by 1832 the Anatomy Act had in some small way helped to stem the flow in the transport of bodies. Although unlike many suggest, the trade in cadavers didn’t stop overnight.

The Turf Hotel was demolished in 1898 following the demise in long-distance coach travel due to the increased popularity of the railways.

Researching The Turf Hotel

*I have only read this once during my research and would welcome any further information if you have also come across such a suggestion. There was a James Syme living in Edinburgh at the time of the Burke and Hare murders but he was a rival anatomy lecturer to Dr Knox, Burke and Hare’s only recipient of cadavers.

Accounts of bodies being discovered in hampers can often be found in newspapers during the years leading up to the Anatomy Act in 1832. I have just shared with you a snapshot of the horrors facing our Georgian ancestors.

Many of the accounts found can be discovered by researching through the historical newspapers via The British Newspaper Archive website on the link here and the main papers mentioned in this post are The Morning Chronicle, Durham County Advertiser and York Herald. Simply searching ‘Turf Hotel Dead Bodies’ should throw you up a few results at least.

The description for the Turf Hotel was taken from Eneas Mackenzie, Historical Account of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Including the Borough of Gateshead. Mackenzie and Dent, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1827