Hidden History of Dunblane Cathedral

On the night of 8th June 1828, a body was stolen from the graveyard at Dunblane Cathedral in Stirlingshire, Scotland.

There’s nothing so unusual about that. This was the height of the body snatching era so you’d expect to find a tale or two within the history books.

What was unusual, however, was that it was still two months before the official dissecting season was about to start.

So why take a corpse now?

Three years later another summer snatching occurred. The body of a ‘poor woman’ was taken from her grave before the dissecting season had even got underway.

What was going on?

A local doctor practising before an operation perhaps? Or were Edinburgh’s resurrection men prowling the graveyard perimeter hoping to fulfil an order and these opportunities were just too good to miss?

In these two short tales playing out in the burial ground of Dunblane Cathedral, you soon come to realise that if a bodysnatcher had his eyes on a cadaver, there was nothing going to stop him.

When was The Dissecting Season in the 19th Century?

As you read on, you’ll probably begin to wonder what’s got me so excited about these two cases.

Very few facts are actually known, so why am I so intrigued? The answer lies in the months that the bodies were taken.

The traditional dissecting season for both Edinburgh and London anatomy schools was October to May. The colder winter months helped to keep the cadaver from decomposing before the medical students had time to dissect it.

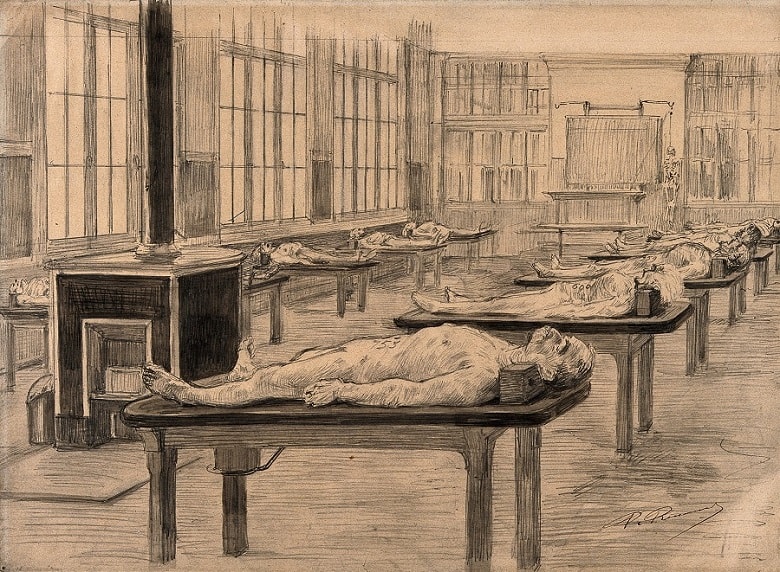

With no refrigeration or preservative measures in place, a cadaver needed to be dissected quickly.

The smell hanging in the air of the dissecting rooms was already bad enough without having to add the smell of a rapidly decomposing corpse into the mix.

Students would have about 10 days to dissect a corpse and learn the inner workings before it was ‘too far gone’ and had to be abandoned.

In the summer months, this period was reduced to half. Hence why most teaching hospitals and Universities were closed and why few private or extra-mural anatomy schools remained open in the summer.

The stench just wasn’t worth it. If you were going to die in the Georgian period, best make it in the summer months.

The Graveyard At Dunblane Cathedral

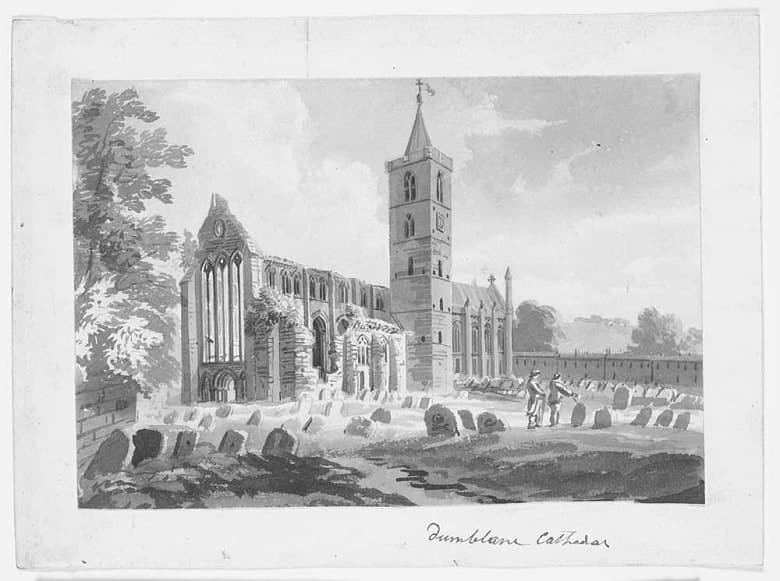

When I visited Dunblane Cathedral, the graveyard was unfortunately all sectioned off. Deemed unsafe for visitors and body snatching enthusiasts. Not so the case in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Built on the site of a previous church, Dunblane Cathedral has been interring the parish dead ever since the 12th century, with the earlier church fulfilling the role perhaps even up to 300 years before this.

When archaeologists investigated the site in 1999, fragments of human bones and glazed floor tiles were found in the nave which, as you will see, ties in very well with our body snatching tales.

The burial ground also threw up some other interesting archaeology:

But alas, not one mortsafe or coffin collar was found.

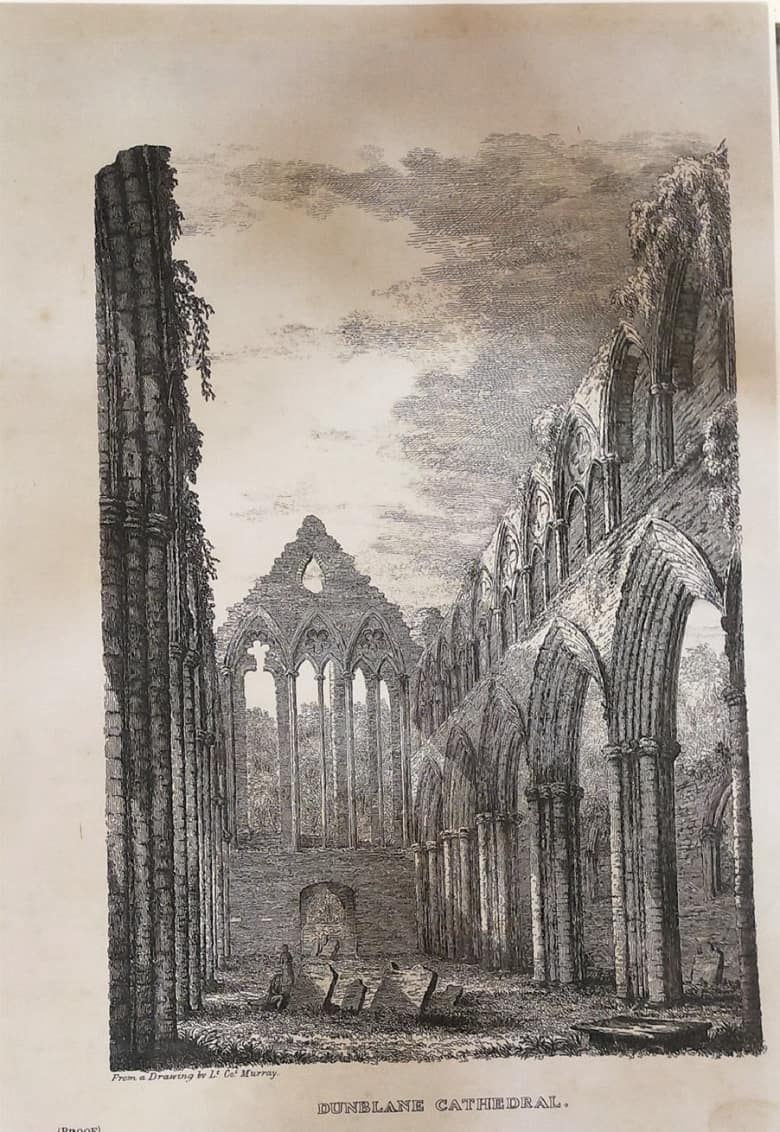

It is the nave at Dunblane Cathedral that holds my interest in this case, for it is here that the parish watch would lurk, waiting the arrival of the resurrection men.

The Ruined Nave of Dunblane Cathedral

Dedicated to St Blane, the Cathedral was a central point in what is the oldest settlement in Scotland.

The nave was all but a ruin at the time bodysnatchers were making a name for themselves.

The roof to the nave, having collapsed around 1600, left this part of the Cathedral exposed to the elements for over 300 years.

When a team of stonemasons eventually began working on the site, the restoration effort resulted in the Cathedral being classed as one of the ‘six best medieval buildings in Scotland’.

Before the new roof was added, however, burials had begun to encroach into the open space of the nave.

An excavation in 1999 unearthed fragments of human bone and after digesting the report written on the Canmore website, we know that by 1560 this area was used heavily as a burial site.

Prints and photographic evidence from the 19th century show the ruined nave with neglected headstones.

These headstones have been flattened, and a ‘well-worn’ path straight down the centre of the site.

As the threat of resurrection men started to appear on the horizon, and the number of burials increased in the graveyard at Dunblane, the inhabitants thought it wise to establish a watch just in case.

The Parish Watch & Dunblane Cathedral Graveyard

By the time of our first snatching, June 1828, a small watch had established itself within the graveyard at Dunblane.

Their role was to remain vigilant for anyone suspicious lurking in the graveyard.

Their nightly patrol encompassed the ruined nave, most likely skirting the perimeter and hugging the walls for protection.

They were armed with lanterns and firearms, and, according to some accounts, cudgels. Quite prepared, some may say, to either shoot the bodysnatchers or beat them into submission if the watch managed to catch them in the first place.

It was usual for a watching party to be protected from the elements with either a watch-house or watchtower being built somewhere in the vicinity of the graveyard.

Most common were watch-houses. Simple stone structures, often with a chimney and just a small window, or two, looking out over the graveyard.

There was no such luxury at Dunblane. When the weather turned and the rain came pouring down, the watch would make a run for it and retreat to a small room in the west gable known as Katie Oggie’s Hole.

Unfortunately, Katie’s hole disappeared in 1889 when restoration work started and I’ve not been able to locate it on any plans that I’ve seen.

Violating The Grave Of An Unknown Subject

Little is known about the first snatching in our tale. All we really know is that it occurred on or around the 8th of June 1828.

This date is given as it’s the date the Kirk Sessions penned a strongly worded letter addressing the Procurator-Fiscal (local coroner and public prosecutor) regarding the snatching.

Demanding that the perpetrators be caught and made accountable for the destruction caused in the graveyard, their words proved fruitless.

The letter had not mentioned any names, the reply stated, so how then was the Procurator-Fiscal able to help?

Not quite the reply that the Kirk Sessions had been hoping for. They responded with a stronger letter, blatantly hinting that the identity of the bodysnatchers was already well-known.

Little good it did them for the case seems to have been dropped shortly after.

The Discovery Of An Open Grave

Our next snatching happened three years later in 1831 and seems to have less information available than the first case.

On the 18th of August, a few months before the dissecting period had really gotten underway, the Perthshire Chronicle shared the briefest of details about the snatching of a female cadaver.

The snatching took place, or so the reader is told, either late at night or in the early hours of the morning and no doubt left the readers in Dunblane more than a little queasy at breakfast.

When parishioners made their way to church the morning of the 18th, they were met with the most sickening sight.

A grave had been left open, the coffin broken and the winding-sheet; that is the burial shroud, thrown back into the bottom.

Thanks to the Perthshire Chronicle, just enough details were reported to put the fear of God into any sickly parishioner knocking on death’s door, and more than enough to get the gossip mongers going.

Rumbled mid-snatch, the bodysnatchers had not only left the grave and coffin open but had also left behind the basket where the woman’s body was going to be stuffed.

And it is here that the story then runs cold. There were no sightings of the bodysnatchers and despite having used ‘all the means available to them’, the trial runs cold.

But Where Did The Corpses Go?

The fate of both the cadavers snatched from Dunblane will never be known, although we can perhaps hazard a guess at their fate.

In 1828, two mail coaches passed through the town daily so there was plenty of opportunity for shipping cadavers away from prying eyes. Plus, a hamper was found next to the grave in the 1831 snatching attempt, strongly suggesting that it was destined to be shipped out of town.

Our second snatching occurred just days before one of the many fairs that were held in Dunblane was about to take place.

The number of strangers flooding into the town to attend the fair would have meant that no one would really have been paying attention to the comings and goings within the graveyard. A perfect situation for any bodysnatcher.

I’ve not been able to find a directory online for this period so I’ve not been able to search for any doctors in the area who were perhaps wanting a cadaver to practise on before performing an operation on a paying customer.

Life was cheap in the 19th century, and if a doctor or anatomist wanted a cadaver, there was always a resurrectionist willing to snatch one.

Dunblane Cathedral Today

Take a trip to the cathedral today and you won’t see any signs of bodysnatchers having been active in the area.

There are no mortsafes or caged lairs in the graveyard, no mention of the parish watch patrolling the ruined nave.

A visit to the Cathedral however is still very much worth it. I had a wonderful chat with the two guides there during my visit, sharing these stories and promising to keep in touch if I found anything further.

I first read about the 1828 body snatching case in Geoff Holder’s Scottish Bodysnatchers: A Gazetteer. The information in Holder’s book is a little out of date for some of the entries now, but it’s still a fantastic reference guide to body snatching sites in Scotland.

I often use it as a starting point for planning my road trips, building on the information through my own research.

Graveyards to Visit In Stirlingshire

There are a few body snatching locations that are worth a visit if you’re staying in the area. Here are my top recommendations that you need to fit into your road trip.

Old Parish Kirk, Logie, Stirlingshire

My first and favourite has to be Old Logie which lies not too far from Stirling. There’s only one word to sum this site up and that is wow!

You’re going to see everything here, and trust me, there’s a lot to see.

Body snatching related, there’s a superb watch-house which is a near-perfect example of what a watch-house should look like.

A tiny window once looked out over the site but this is now bricked in, and there’s a small chimney indicating the presence of a fireplace inside.

The Kirk on the site is now a ruin but dates back to the 17th century. It creates a terrific atmosphere on the site.

The original Kirk dated from the 12th century, so the ruin that you see before you is actually the ‘new’ or replacement Kirk.

You’re going to be blown away by the memento mori, that if you’re anything like me, you’ll be flitting between gravestones as you keep spotting skulls here, there and everywhere.

There’s even a hogback stone dating to the 11th century on the site.

Park at the modern cemetery below and take the short walk up the old parish Kirk, I guarantee you’ll not be disappointed.

The Church of The Holy Rude, Stirling

You can’t come this close to Stirling and not pay a visit to the infamous Church Of The Holy Rude.

Also known as the Old Town Cemetery, this is the home of the famous ‘ Pink Lady’. This apparition is thought to be the ghost of Mary Witherspoon, one of the few victims of the resurrection men her at Stirling.

If ghosts are your thing, I think you’ll enjoy this guest post on my blog by Spectral Isle, all about ghosts, graveyards and body snatching

Old Parish Kirk, Aberfoyle

A little further away from Dunblane but still in the county of Stirlingshire lies Aberfoyle and the mortsafes you’ll see here, definitely make the trip worthwhile.

Two heavy iron over coffins or iron mortsafes are displayed on either side of the doorway of the now ruined Kirk and the setting for these two relics couldn’t be more fitting.

The last time I was there it was foggy with a persistent heavy drizzle and it was just perfect.

If mortsafes are your ‘thing’ and let’s be honest they are pretty fantastic, then you may find that one of my earlier posts all about mortsafes and how they developed, could be just what you’re looking for.

Aberfoyle is also the burial place of the ‘Fairy King’, the Rev. Robert Kirk. His grave is tucked at the back of the Kirk, the southeast side. You can’t miss it for it’s covered in coins and pretty low to the ground.

Rev. Kirk was a folklorist fascinated by fairies, but after taking his usual evening walk up Doon Hill, also known as Fairy Hill, one evening in May 1692, he was found dead on the summit.

Rumour has it that the body found on the summit that day, and that was subsequently buried in the Kirkyard was that of a changeling and not the Rev. Kirk.

Many believed that the fairies had swapped bodies as they were angry at him for prying too close into their secret world. Legend has it that the good Reverend is instead imprisoned forever in the Clootie Tree high up in on Doon Hill.

Although there’s limited parking at this site, trust me when I say you’ll definitely want to add it to your list.

Enjoyed Reading This? Why Not Pin It For Later?