The Simple Art of Burking

This post may contain affiliate links. Please see my disclosure policy for details.

The term ‘Burking’ had already been a staple in the English language and bandied about by the Press even before the end of 1829 had ended.

The same year that Edinburgh murderer William Burke, after freshly hanging from the gallows had put his name to a murder method now synonymous with suffocation.

But what exactly was ‘Burking’ and how did it enter into everyday terminology in the first place?

Using the British Newspaper Archive, I’ve taken another look at just a few of the reports that mention Burking and share with you some of the lesser-known, as well as the more famous accusations made surrounding this particular murder method.

Table of Contents

What Is Burking?

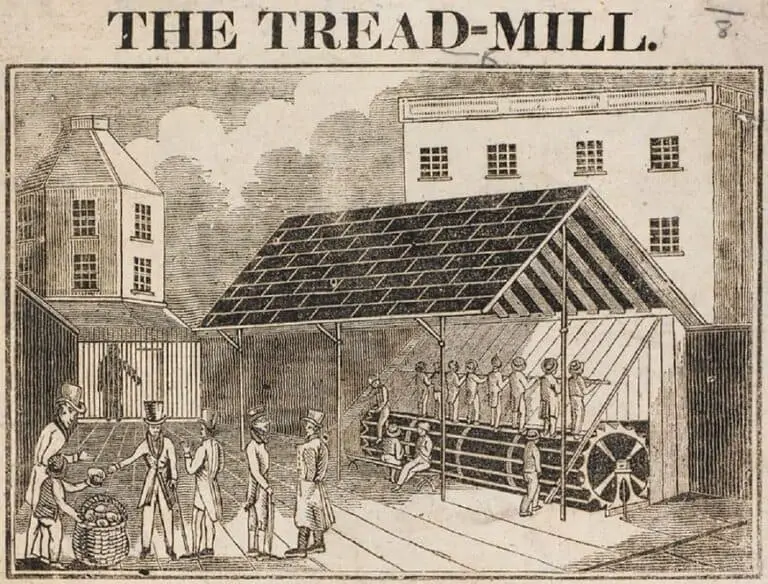

If we look at it in a historical context, Burking describes the method used by Edinburgh murderers, Burke and Hare, to kill their victims.

While Burke held down the victim and restricted their movements, William Hare was the asphyxiator, covering the nose and mouth with his hand.

The term Burking is derived from the murder method used by Burke and Hare during their killing spree in Edinburgh in 1827-28. The term appeared regularly in the tabloid press after William Burke was hanged on 28th January 1829, after which it was used to describe all manner of attempted assaults. The word Burking became feared, the press whipping up hysteria for a crime that became synonymous with murder for dissection.

They’d perform this task interchangeably, each taking the role of murderer and accomplice.

Before we go any further, if you want to know the story of Burke and Hare in more depth, then feel free to head over to my post on the complete history of Burke and Hare. Here, I’ve tried to answer all your questions, such as, did Burke and Hare have children where did they sell the bodies? And, the one most people are curious about, how much money did they actually make? Although, follow this last link if you want a full-blown account of the prices they received for each cadaver, etc.

The general consensus of a definition of Burking however is this:

Burking means the crime of murdering a person, ordinarily by smothering, for the purpose of selling the corpse. The term derives its name from the method, William Burke and William Hare, the Scottish murder team of the 19th century, used to kill their victims during the West Port murders

https://definitions.uslegal.com/

After Burke was hanged and later dissected at Edinburgh University, the press fed on the public’s fear of being assaulted. They honed in on their fear of being attacked from behind and suffocated with a medical pitch plaster, a fictitious method that historian Dr. Ruth Richardson believes was developed in the interim period of Burke’s arrest and final confession.

It is this fear, formulated in the public eye, and subsequently whipped up by the press, that not only led to tall stories in the papers but also turned any attempted assault into a supposed ‘Burking’.

‘Burking Mania’, ‘Burkiphoby’, and even ‘Burkophobia’ were, as Richardson points out, a very real phenomenon.

Burking By Means Of Arsenic-Laden Snuff

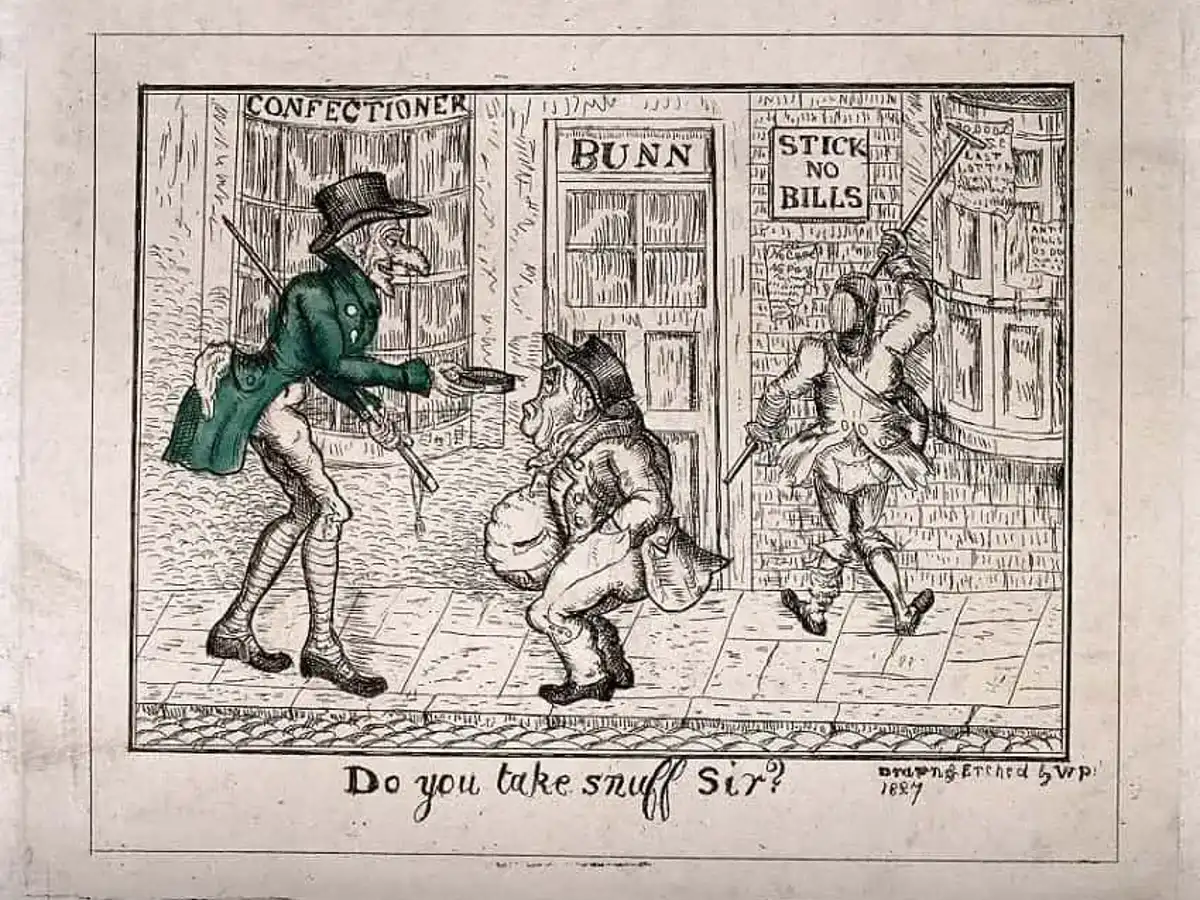

Taking my lead from James Blake Bailey’s fabulous account of resurrection men in London in ‘The Diary of A Resurrectionist’, I want to turn first to a fanciful tale relating to Burking by the means of arsenic-laden snuff.

A gentleman by the name of John Wilson was accused of ‘Burking’ numerous people in a rather ingenious manner. Arsenic was added to a quantity of snuff kept in a box in his pocket and whenever he came across a likely victim, he’d a fictitious question, and, following their reply, would offer them snuff as a way of thanks.

Wilson’s Modus Operandi seemed to be a trusted method for it is said that when he was finally apprehended, there were three dead bodies in the back of his cart, on the way to who knows where!

Wilson’s demise finally came when he met a labourer breaking stone on the road between Lauder and Dalkeith. After inquiring as to the distance to Edinburgh, Wilson offered the labourer some snuff.

The offer was politely declined.

Mr Wilson’s Dowfall

Becoming insistent, the labourer was forced to take a pinch, which he wrapped carefully in paper and placed in his pocket.

After having it analyzed with a chemist in Dalkeith, it was found to have arsenic mixed through it. The snuff was immediately seized and the search was on for the elusive Mr Wilson.

When he was finally apprehended, Wilson was taken to Edinburgh and questioned for two hours before the judge passed a sentence of wilful murder. John Wilson, once so sure of himself, was led away to Calton Gaol to await a trial at ‘the ensuing sessions’.

‘Burking in England’

Accounts of ‘Burking’, be they fact or fiction, appeared quite regularly in the press and must have put the wind up many a family when father was reading out the newspaper over toast and tea.

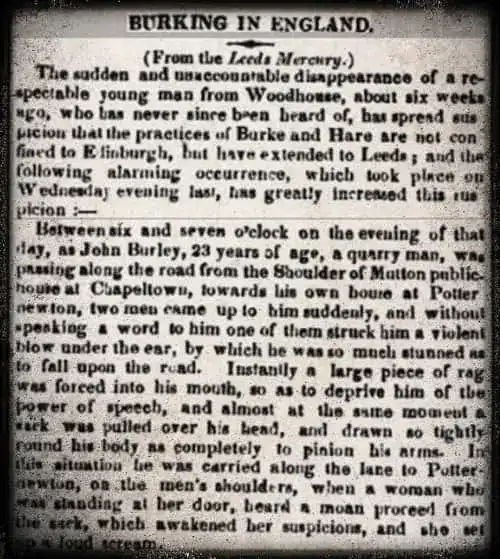

In January 1830, a familiarly styled article appeared in the Morning Advertiser with the headline ‘Burking in England’.

The account, as you can see below, told of two men suddenly attacking 23-year-old quarryman, John Burley as he walked along the road from the Shoulder of Mutton pub in Chapeltown, a part of Leeds.

Punching him under the ear and sending him off guard, Burley then had a rag stuffed into his mouth and a sack pulled over his head, pinning his arms to his sides.

Thank goodness Burley moaned, for his plight alerted Mary Smith who was standing in her doorway and who let out, what appeared to be, a very loud scream.

The scream seems to have done the trick, for Burley, completely helpless, was immediately thrown over the nearest wall, landing 6ft down into a field owned by Mr Waile.

Landing safely, Burley was quickly pulled out from the sack and when he was able to speak, immediately stated that ‘he believed it was the intention of the men…to Burke him’.

Was this true?

We will never really know for certain but the headline shows that ‘Burking’ was still very much in the public’s mind, even nearly a year after William Burke’s end.

‘Apprehension of a Supposed Burkite’

Towards the end of November 1831, cries of “murder” were heard coming from Webber Street, near the Coburg Theatre, Lambeth.

14-year-old Thomas Hammond was in the middle of being kidnapped by ‘go-cart driver’ James Gardiner who had seized him by the arm and was attempting to drag him away when his cries were heard by neighbours.

As constable No. 93 George Hunt of ‘L’ Division was arresting Gardiner, it turns out that perhaps the boy’s cries of ‘murder’ were not dumbfounded after all.

Standing at the bar being interrogated by Messrs. White and Heathcot, on that November day in 1831 a story began to emerge which seemed to imply that Gardiner was in the habit of carrying out this form of assault.

Alarm bells began and the Webber Street foundry owner, Mr Fowler, who was standing in the crowd listening to the examination believed he’d heard similar stories involving one of ‘his boys’ and decided to step forward.

One of ‘his boys’ was Charles White, also 14, who had had a similar, if not more disturbing assault happen to him only a few days earlier.

On walking home the young boy saw Gardiner coming out of a brickfield. After acknowledging each other, White crossed the road but happened to glance back and saw something in Gardiner’s hand.

Thinking this to be a plaster, White called out for help at which point Gardiner ran forward and clasped the said plaster over the young boy’s face so that he could barely speak or breathe.

Suddenly, a second man came up behind him, seizing him by the neck and tried to throttle him.

Poor Charles White I hear you cry! And quite rightly so, for it does indeed appear that he was being ‘Burked’.

Suddenly Charles was thrown over a nearby wall into a hole. Luckily he managed to remove the plaster and make his escape back home, but the plaster had left its evidence over the poor boy’s face.

The assault was taken seriously at the local police station:

His [Charles’] face was covered in black stuff, and with some difficulty, it was got off with a towel … The towel used to clean his face was left there [at the police station] and would show what sort of stuff had been used.

Gardiner was not known to the local police and both boys easily identified him during questioning. The magistrates, not convinced of his innocence, however, remanded Gardiner in custody until the following week.

The examination of James Gardiner happened barely one week before the trial of Bishop, Williams (alias Head), and May, the famous ‘London Burkers’. Coverage in the press was dominated by their trial, and it is difficult to find further entries, relating to Gardiner.

Burking or Murder?

There are two famous cases that are recorded in the history books as burking when in fact they are essentially murders.

You are probably familiar with them both as they have both been sensationalized by the press at some time or other and their stories get dragged out from the archive at suitable times of the year.

Jean Waldie & Helen Torrence

I’ve written about these two women before as Edinburgh’s first body snatchers, and their story is familiar to a lot of people. But did you know that they are also referred to as ‘Burkers’.

After their plans to offer the body of a dead child to the surgeons fell through, in March of 1752, they needed to find a replacement and fast.

They decided on the 9-year-old son of a friend, a sickly boy named John Dallas.

Dallas rarely, if ever, left the house. In fact, when Waldie went to ‘fetch’ the child, he was found leaning against the windowsill, gazing out of the window. It was thought his disappearance wouldn’t be noticed.

By all accounts, the snatching of the child seemed to be rather simple. Waldie, gaining little John’s trust, coaxed him slowly out of the house and wrapped him in her petticoats on the way back to her house to keep him warm.

Unfortunately, he was dead by the time they got there. Suffocated in the voluminous expanse of frills of Waldie’s petticoats. I suppose it saved Waldie the job of murdering the child when they got home. A more peaceful end to John’s short life perhaps.

Both Waldie and Torrence were hanged for their crime after the students who were offered John’s body became nervous on hearing rumours that John had disappeared.

They dumped his half-anatomized cadaver in a small close of Libberton’s Wynd in Edinburgh and the chain of events to catch a killer was put into place.

It didn’t take long for the body to be discovered and for Waldie and Torrence to be arrested for the act. A few well-targeted questions to the neighbours saw to that.

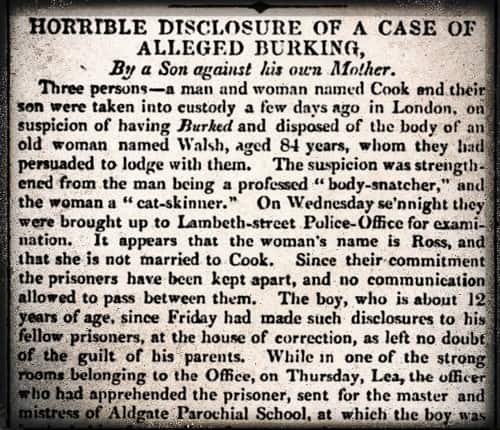

Eliza Ross alias Cook

Eliza Ross was also known as Eliza Cook, occasionally taking the surname of her common-law husband Edward Cook. The former was a ‘cat skinner’, the latter a ‘professed body snatcher’.

The tale of her downfall is a confusing one and one that is difficult to surmise in a few short paragraphs. Already having something of a reputation, Ross’s last cadaver for the surgeons is a complicated tale indeed.

An Irishwoman, who by all accounts possessed a fiery temper that she had difficulty controlling, Ross lived in Goodman’s Yard, in the East End of London, and by 1831 she was already suspected of supplying cadavers to the surgeons.

Her move to 7 Goodman’s Yard had been accompanied, after much persuasion, by her lodger, 84-year-old Caroline Walsh.

Despite the increasing pleas from Caroline’s granddaughter Anne Buton for her not to accompany the Cook’s, her reservations fell on deaf ears and Caroline Walsh made the move to Goodman’s Yard with the would-be murderers.

The Murder

On calling round to see her grandmother the following morning, Anne was surprised to find her out, even though she’d given specific instructions to wait in for her visit.

The conversation that passed between Buton and Ross that morning is perhaps best expressed as dialogue. Curious as to the whereabouts of her grandmother, Buton doesn’t hold back in asking Ross where she could be.

They’d enjoyed a jolly good supper was Ross’s reply. I take you to the kitchen of 7 Goodman’s Yard to listen in to the rest of the conversation …

[Buton] Glad you enjoyed yourselves. May I take the liberty of asking what was in it?

[Ross] Potatoes and meat. Me ‘usband went and got ‘er [Walsh] some spirits and a sack, which we’s doubled up and put ‘er [Walsh] in it.

[Ross is washing a jacket in the sink]

[Ross] I can wash anything for you if you’d like. Petticoats, linen. She wasn’t wearing any linen under her dress you know

It seemed Eliza just couldn’t keep her mouth shut and it was to get worse after she invited Anne to a gin shop on the corner of Goodman’s Yard and the Minories.

Let’s join them at a nearby table…

[Ross] From what you say, you seem to think we murdered the old woman.

[Buton] I hope not

[Ross] From what you say, you think we destroyed here at our place.

[Buton] Mrs Cook, you put the words in my mouth. What I suspect I don’t say now. But you shall hear of it all at length

After a two-month search, and after being rebuffed by the police, Buton finally found the information to suggest that Ross had tried to sell her grandmother’s petticoats to a rag dealer.

By November Eliza’s story was beginning to reach the papers, this time stating that her son had witnessed a burking.

Things were not looking good for Ross.

‘Little Ned’, the couple’s 12-year-old son has witnessed his parents drug the 84-year-old Caroline Walsh with some coffee, presumably laced with laudanum. It was while the old woman was feeling the effects of this drug that Ross smothered the woman with her hand over her mouth and nose while her ‘husband’ Edward Cook, gazed out of the window, observed unknowingly by little Ned.

It took nearly an hour for Eliza Ross to expire on the scaffold in January 1832. After being left to swing for the legally allotted time her body was cut down.

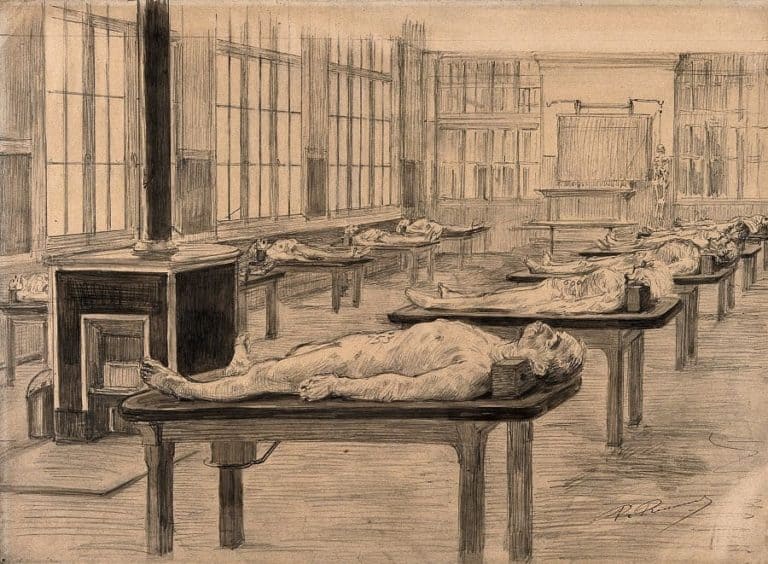

As part of her trial at the Old Bailey, on 5th January 1832, her body was to be sent for dissection. And so it was that she was conveyed in a cart to anatomists waiting at Surgeons Hall.

Eliza Ross, formerly of 7 Goodman’s Yard, was the last person to be sent for dissection as part of their punishment.

But, true to form, Eliza hadn’t finished just yet for her body, or rather an impression of it, turned up only eight months later, in the form of a waxwork at No. 167 High Holborn.

Too much excitement, and with the parting of a penny, Eliza Ross, along with Bishop and Williams and a few other ‘notorious characters’ could be seen filling out ‘four large rooms’ as

…full length figures in accurate likeness …dressed in the identical clothes in which the several originals appeared when last in existence … the whole arranged with consummate ability, so as to produce a most imposing effect

could be seen.

Researching The Art of Burking

It wouldn’t take you long to discover something in contemporary newspapers relating to an account of ‘Burking’ but as James Blake Bailey quite rightly points out, many of these accounts are fabricated in an attempt to excite the public and presumable to sell more copies of the newspaper.

There’s no denying that Dr. Ruth Richardson’s book ‘Death, Dissection and the Destitute’ is legendary in the world of body snatching and her research on the mania surrounding the ‘Burking’ phenomenon helps to shed light on the frenzy created by the press.

If you do have Richardson’s book or you’re thinking of buying it, then chapter 8, Bringing ‘Science To The Poor Man’s Door’ is certainly worth a read on the subject.

I turned to Martin Fido’s book ‘Bodysnatchers‘ (now sadly unavailable) and his account of Eliza’s story for this post and I drew inspiration from his text in writing her story with dialect. I have embellished it a little but the facts are still there, Eliza couldn’t keep her mouth shut and her ramblings subsequently led to her downfall.

The British Newspaper Archive (£) has digitized the newspapers covering the story although, at the same time the ‘London Burkers’ were also making headlines, so it can be a long trawl to get to the entries relating to Eliza Ross and the part she played in the history of medicine.

Please don’t let this put you off searching though, as there are some real gems tucked away in there such as the article written in 1832 regarding Eliza’s waxwork.