The Wardsend Body Snatching Scandal of 1862

When sexton Isaac Howard was accused of selling corpses to Sheffield Medical School in 1862, you shouldn’t really be surprised to hear that a mob gathered in the cemetery concerned and tried to lynch the man.

It had been thirty years, nearly to the day, since the Anatomy Act had promised to end the illegal trade in corpses, but the events that played out in Wardsend Cemetery, just on the outskirts of Sheffield, were proof that it was still very much alive.

On 3 June 1862, sexton Isaac Howard was accused of exhuming cadavers from and selling them to Sheffield Medical School. During an extensive search of the site, 20 coffins were discovered piled into a pit along with evidence of dissected remains. The coffin plates from 24 coffins were also found which corresponded with missing corpses.

But as the story unravelled, a much sinister side to the underhand methods at Wardsend Cemetery started to emerge.

In this post, I’ve pieced together the accounts as they were reported in the newspapers and taken a closer look at this notoriously late body snatching scandal.

Wardsend Cemetery: An Introduction

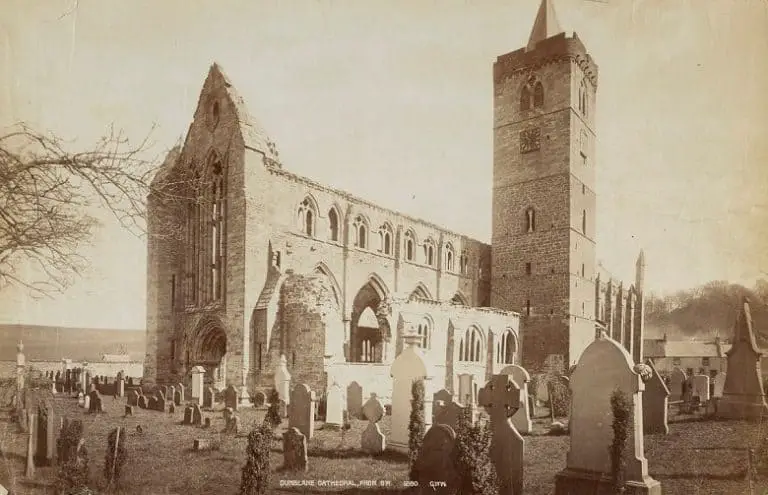

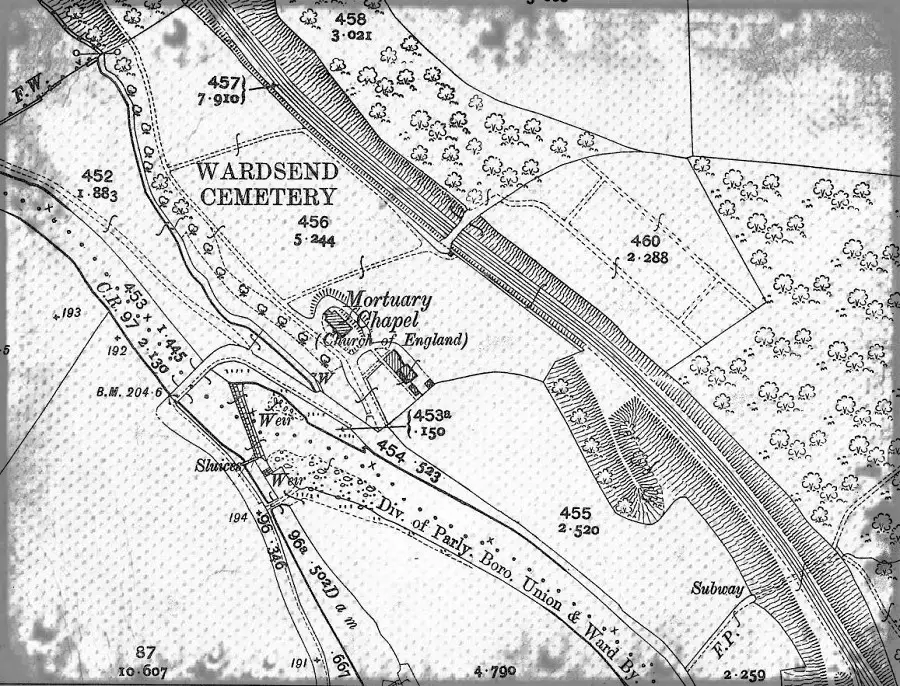

Wardsend Cemetery was a relatively new addition to the Sheffield suburb of Hillsborough in the years after the Anatomy Act.

Although there was a churchyard already in use in the district, this was rapidly becoming overcrowded and by 1857, the current graveyard at St Phillip’s was almost full.*

Foreseeing the graveyard’s imminent closure, a new five-acre site at Wardsend was purchased that very same year by the incumbent of St Phillips’s, Reverend John Livesey.

After using most of his own money to purchase the site at a cost of £2600 (that’s nearly £154,000 today) its first ‘’inhabitant’ 2-year-old Ann Marie Marsden was interred even before the site had been consecrated.

Things at the cemetery ticked along nicely until the summer of 1862.

The Discovery of Empty Coffins at Wardsend Cemetery

The first hint that something was afoot at Wardsend Cemetery was a report in the Sheffield Independent, dated 4 June 1862 entitled ‘Extraordinary Riot at Hillsbro’ Last Night. A House Burnt Down’

After recently renting the house in the middle of the cemetery from the sexton, labourer Robert Dixon started noticing a noxious smell emanating from the rooms above a nearby stable.

As the weather grew warmer, the smell grew steadily worse and Dixon decided to investigate its source. Knocking a small knot of wood from the flooring in the stable, he gingerly peered into the room below.

I doubt anything prepared him for what he saw next which he described at the trial in July 1862:

‘I saw about 20 coffins – some of persons about 15 and 16 and 10 years old – others were those of stillborn children. None of them appeared to be in the coffins of grown-up persons… the coffins were not covered over with anything and were lying in a heap on the ground piled in heaps on top of each other.

Curiosity getting the better of him, Dixon investigated further.

I lifted the lid [of a coffin] with my toe, and saw the face of the body. It looked very fresh, as though it had been buried a week or two. It looked like the face of a boy about 15 years of age.’

Rumours of Dixon’s discovery spread rapidly through the neighbourhood and when the sexton, Isaac Howard, innocently arrived at the cemetery to carry out internment on 3 June, he was met by an outraged mob who quickly turned on him, unwilling to accept any excuses.

He narrowly escaped after the police intervened, but the mob hadn’t quite finished with him and their next target was Howard’s home half a mile away at Burrowlee. It was here that the mob let their real fury for Howard’s unsavoury acts be felt.

The Wardsend Cemetery Riot

The beginnings of the riot really started at Howard’s home with the mob descending like locusts, determined to destroy anything he’d laid his hands on.

The efforts of Howard’s wife to calm the mob proved futile and her continued instance that her husband wasn’t there fell on deaf ears with the rioting continuing unabated.

The mob finally entered the house as darkness fell, gathering furniture and piling into a bonfire in the front parlour.

And then someone suggested they set it on fire, and by midnight all that remained were the walls.

A Mass of Human Remains Discovered in a Pit

In light of the destruction inflicted on Howard’s home, parishioners grew more anxious at the news coming out of the cemetery and they flocked to check that their loved ones were safe.

A mass frenzy of digging commenced. And then to their absolute horror, they found the pit.

In an unused part of the cemetery, referred to as Section A, a pit of nearly 15ft deep was discovered covered over with loose boards in which lay a jumble of coffins.

As the finds in the pit were examined and the digging got deeper, a ‘mass of human remains’, or as the Birmingham Daily Post put it ‘a mass of rotting matter’ was discovered:

‘a mass of human remains several feet in thickness, which … have … accumulated by the throwing of dissected bodies into the hole without coffins, and [by] the emptying of bodies from coffins removed from the graves in the cemetery’

The panic at the cemetery intensified as a second party discover further evidence of wrongdoing in the stable:

‘A number of coffins and 24 coffin plates removed from coffins which had been placed in the ground within the last three years, were found…’

The names of those written on the coffin plates were published in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph as follows:

| Name of Deceased | Date Died | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Anne Shearer | February 26, 1858 | 7 years |

| Sarah Ellen Durden | March 7, 1858 | 7 months |

| John Lilly | March 14, 1858 | 4 months |

| Charles Wood | March 22, 1858 | 14 months |

| Louise Bacon | April 9, 1858 | 4 months |

| Sarah Ellen Frost | April 24, 1858 | 1 year |

| Mary Roberts | April 28, 1858 | 2 years |

| Charles Hinchcliffe | May 6, 1858 | 2 years, 11 months |

| Charles Marshall | May 12, 1858 | 5 years |

| Richard Henry Parker | May 23, 1858 | 9 months |

| William Henry Cornall | May 23, 1858 | 3 years |

| John Beatson | July 29, 1858 | 4 years |

| H. B. White | August 15, 1858 | 2 years 4 months |

| Sarah Jane Davis | October 16, 1858 | 5 years |

| Emma Willett | December 28, 1858 | 1 year, 1 month |

Back at the burial pit things were about to take a grim turn for the worse. Mrs Harrriet Shearman whose young son Edward Charles had been buried in the cemetery at the charge of 1s the previous December, was about to come face to face with her son once again.

As those around her were finding empty coffins, Mrs Shearman looked closer at a coffin where the lid had slipped off and ‘recognised the features of her own child’.

Probably out of an act of desperation and a mother’s natural protection, Mrs Shearman would take the body of her dead son home with her for safety.

The Body In The Box

But still worse was to come.

The discovery of dissected remains in a box, measuring 3ft 6” in length, 20” wide and about 17” deep was found slung into the pit.

As the lid was slowly opened, a gentleman’s torso and limbs, with ‘flesh having been removed from the bones’ were exposed.

It was then that the realisation dawned. The Pit had been used to sling dissected remains received from the nearby Sheffield Medical School.

Sending Cadavers For Burial

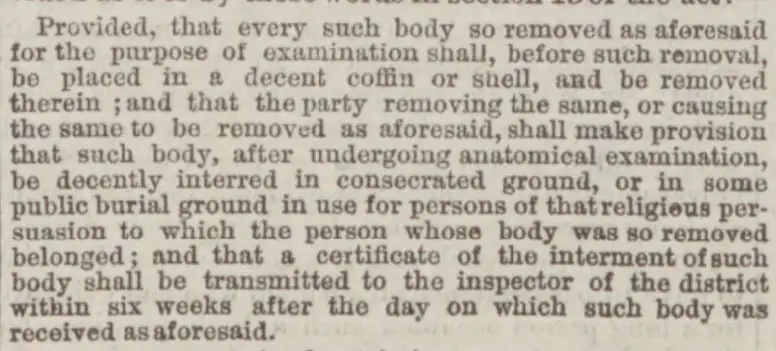

The School, located in Surrey Street had, according to the Anatomy Act of 1832, been granted ‘the use’ of the unclaimed poor from the workhouse and after cadavers had been collected in ‘the usual way’; that is in a sack rather than in the proper manner of concealing the corpse in a coffin, the medical room porter, Moses Walton, had little to do with the corpse then until the anatomists had finished with it and it was time for burial.

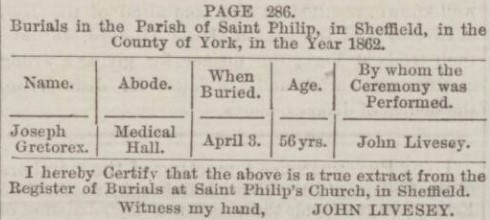

The man in the sack on this particular occasion was Joseph Gretorex whose body had been collected from Sheffield workhouse 10th March 1861. Gretorex remained with the Medical School until 12th April when his body was then placed into a box and taken to the cemetery by Isaac Howard.

In good faith the school sent the dissected cadavers to the cemetery to receive a ‘decent funeral’ giving thanks to their part in medical science, they were completely unaware of what was happening at the cemetery.

It was customary for the Medical School to pay for the removal of the cadaver after dissection, giving the sexton 5s when he fetched the body and then a further 13s for the internment. This last payment included the cost of the coffin and the burial fees.

It was becoming steadily clearer that the owner of the cemetery, Rev. Robert Livesey and the sexton Issac Howard, had been involved in something corrupt.

Congestion at the graveyard had caused Howard to act in the way that he had. To save on space, and to ensure that the cemetery could continued to accept burials, Howard had been removing the coffins from the unpurchased graves:

‘Room was wanted in the ground and the bodies of children were removed because they were the soonest decayed’

And so the pit had been dug to act as a form of ‘Charnel House’. The coffins and coffin plates of those he emptied were the ones found by the family members in the stable.

As far as the ‘mass of rotting matter’, well this was the remains of the ‘unclaimed poor’, slung into the bottom of the pit after dissection at the Medical School, even though they’d acted in good faith and paid Howard and Livesey for a decent burial.

The Trial

Although this case is referred to as a body snatching case, it really isn’t. Isaac Howard didn’t remove corpses to give to the Medical School, he removed them to make way for more funerals. The bodies never left the cemetery.

In Howard’s statement, he expressed that the orders to remove the coffins had come directly from the Incumbent himself. The bodies of those buried in 1857 and 1858 could all be removed and put into the catacombs ie. the pit.

A ‘legal register’ of the removals had been kept by the Incumbent according to Howard’s recording:

‘ when the bodies were interred, who they were, their ages, where buried from, and the numbers of the graves they were buried in, and when buried. The register will give the numbers of the graves which are in the ground book, and there are dots in the ground book which show those numbers that are done with and a fresh number is made for those who are put in’.

Howard was charged with an offence against public decency although there was still some doubt as to who had sanctioned the removal of the coffins in the first place. The jury was asked however if they thought Howard had acted alone and without authority, they should find him guilty of a misdemeanour.

Their guilty verdict was returned immediately and Howard was sentenced to three months imprisonment.

Rev. Livesey received a much lighter sentence for his part in the affair, although public hatred towards him was still high, so much so that it was advised that the Judge pass sentence immediately.

Accused of falsifying entries in the burial register and supplying fraudulent certificates, Rev John Livesey was persistent that he was unaware of the removals or even the receipt of dissected remains from the Medical School.

Summing up the Judge tended to believe Livesy’s claims and said:

‘ I shall give you a very short sentence of imprisonment, because I feel strongly that what you say is most probably the truth of this case’.

Livesey did indeed receive a short sentence, three weeks imprisonment in the County Gaol. However, this was backdated to the start of the Assizes which has already been in session for two weeks and so Livesey’s time in Goal was actually only one week.

An Unjust Sentence

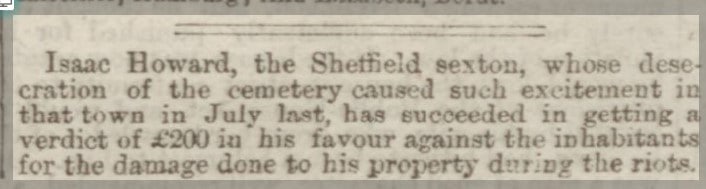

In November, five months after the initial trial and the riots at Wardsend, a claim for damages was submitted from both Isaac Howard and Rev. Livesey.

In the tiniest report ever in the Dundee Advertiser, we learn Howard has succeeded in being awarded £200 against the damage done to his property. The damage caused to Howard’s home had been estimated at £500 at the time of the riots so £200 in compensation was a bit of a shortfall.

Details of the claim were as follows:

A total of £376. I can find nothing reporting how Howard felt about this shortfall, but Isuspect if he had the sense to remain quite.

Rev. Livesey also claimed damages to the church property; £281 to the freehold of the cemetery and buildings, £17.1s 6d for damages to the furniture, books etc in the vestry but I have been unable to find any record as to whether this was awarded or not.

Researching The Sheffield Body Snatching Riot

*There is no longer a church on the site at St Philip’s, formerly on Infirmary Road. I understand it was destroyed during the blitz of 12 December 1940 and eventually, the site was cleared in the late 1950s.

The trial of sexton Isaac Howard was covered extensively in the British newspapers and a quick search in the British Newspaper Archive (£) holdings online should bring reports up almost straight away.

For a detailed account of the trial and the summoning up of the Judge then I would suggest reading the Sheffield Independent from Friday 25 July 1862.

There are a lot of details to this case which, for interest reasons, have been summarized for this post. If you would like to read more, then I encourage you to follow up on the case in the newspapers.

![‘[A] Miraculous Circumstance’](https://mymacabreroadtrip.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Rawlinson-Resurrection-Men-via-Wellcome-Library-Diggingup1800-768x934.jpg)