5 Ingenious Forms of Body Snatching Prevention

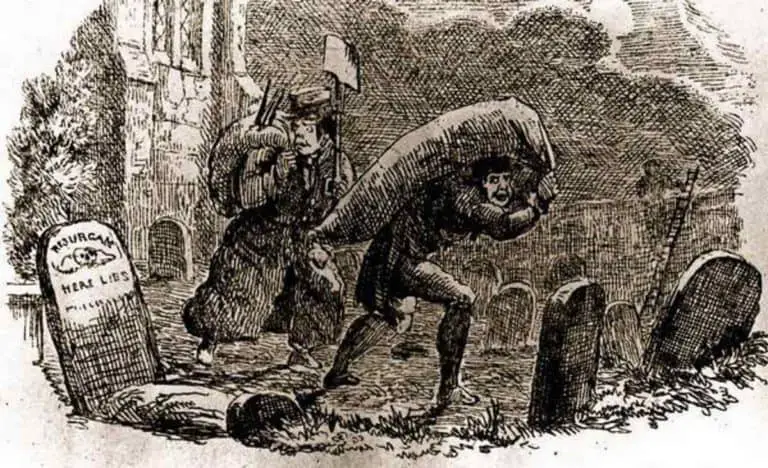

Fear of the ‘bloody body snatcher’ was ever-present during the first few decades of the 1800s. There probably wasn’t a parish in the land that hadn’t heard of or been targeted by a body snatcher in some way shape or form.

But not all parishes, or even people for that matter, trusted the more conventional types of body snatching prevention such as a mortsafe or the more elaborate caged lair and as the pressure mounted for parishes to protect their recently interred, new and alternative methods of prevention started to spring up across the country.

I have a few firm favourites, probably the coffin collar, for reasons which shall become apparent later, but I also like the ingenuity of those fathers out there who would stop at nothing to protect their daughters’ graves; my favourite being the one who was adamant that he was going to use gunpowder as a means of ensuring his daughter didn’t end up on the dissecting table.

In this post, I’m going to look at just a few of the more adventurous forms of body snatching that I’ve come across during my research, including:

But while I’m sure that I haven’t come across all the bespoke forms of body snatching prevention that would have been devised, especially by the poorer members of the parish who may have felt it necessary to move beyond small piles of sticks, the five that I cover in this post are certainly ones that have stuck in my head over the years.

Some of the methods mentioned below you may already have heard of, others may be new to you, but I hope my selection shows just how far some individuals would go to protect their dead from the hands of the surgeons.

The Humble Coffin Collar

Ah, the humble coffin collar. Such a simple idea that, as far as I’m aware, wasn’t that widely used. The idea behind the coffin collar was to literally strap the corpse down to the base of the coffin by its neck.

The iron collar would be fitted around the corpse’s neck and subsequently bolted onto a piece of wood. This in turn would be fastened to the bottom of the coffin, either by nails or screws, when the corpse was laid inside.

This meant that when a body snatcher tried to pull the cadaver out of the coffin, short of having to remove its head, which wasn’t unheard of, the corpse would stay put and the body snatcher, in an ideal world, would move onto another grave.

The most well-known example of a coffin collar is that which is currently on show in the National Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh. It sits practically alongside perhaps the biggest iron coffin I have seen to date and demonstrates the lengths that our ancestors went to, to protect our loved ones.

Finding Other coffin Collars

This particular collar once belonged to the parish of Kingskettle in Fife, but there are other examples of this type of prevention that has also come to light. Others are known to have survived from St Andrew’s Cathedral and Monimail both in Fife, but I believe they have long since disappeared. [1]

When I was carrying out research for my book,[2] I also came across a coffin collar that was discovered in Glasgow whilst digging a grave. The collar had been in use in the North West Burial Ground in the city and had been found in 1833, barely one year since the Anatomy Act had been passed.

The description that accompanied the report in the newspaper read as follows:

Two semicircles of iron, which had encompassed the neck and ancles (sic) of the corpse

This seems to suggest that more than a coffin collar was found and indeed used, although I could find nothing to suggest that the corpse was still in the coffin when they found it!

Most recently in the BBC2 series ‘Britain’s Biggest Dig’ which I’m thrilled to say, I got to be a part of, even if it was just for a short while, a coffin collar was discovered during the archaeological dig at St James’ burial ground in London.

It was traced back to its ‘owner’, 55-year-old Sarah Beaton who had died in 1819. What a find and imagine researching the history behind it! Some great work by the researchers.

Gunpowder In The Coffin

There’s extreme and then there’s putting gunpowder in the grave of your loved one!

Such was the fear of the body snatcher that some people were even willing to blow up family members rather than risk them ending up on a dissecting table.

I’ve read a number of reports involving gunpowder being placed into a grave but the most bizarre, as well as the most extreme, perhaps comes from a report found in the Liverpool Mercury, dated February 1824.

The method used a two-pronged attack against the resurrection men, the first being to secure the head end of the coffin into a recess in the grave.

The plan was dreamt up by a Northumberland landowner who was thoroughly sick of corpses disappearing from his patch. His idea was to dig a shorter grave and to cut a recess into the solid, compact soil at the side of the grave so that the head end of the coffin could slide into it.

This would then prevent the body snatchers being able to use their usual method of digging down and breaking open the coffin lid and extracting the corpse.

If however, the body snatcher did manage to gain access to the cadaver, then the second part of the plan would come into play.

On a wire inside the coffin was placed a mixture of gunpowder and percussion powder (?) that was designed to explode as soon as the coffin lid was tampered with.

With a ‘shelf life’ of one month, this ensured that the corpse would be suitably decomposed and thus rendered useless to the anatomists by the time the effectiveness of the explosive wore off.

If the body snatcher did however gain access, there was no solution given in the newspaper as to who, or how, the mess would be cleaned up.

Gunpowder was also the prevention method of choice in 1823 when the funeral of a young girl took place in Dundee. Her father, fearful that the resurrection men would strike, placed a small box filled with gunpowder inside the coffin that was attached to the lid by a series of wires. If the lid was removed in any way, and we all know how a body was exhumed, then the powder would explode.

Naturally, the sexton refilling the grave on this occasion was nervous in case his actions triggered off an explosion.

Man-Traps And The Ingenious Cemetery Gun

Adapted from a poacher’s gun, the cemetery gun indeed looked threatening, but for the professional body snatcher they could often prove ineffective. It was better to have an armed guard in the graveyard where the professional body snatcher was concerned.

The idea alone was clever. Rig up a poacher’s gun with a series of tripwires emanating from the trigger. In the dark, these wouldn’t be seen and the gun would fire at the body snatcher trying to raid the grave.

This proved useless, however. Scouting parties would have noticed any prevention methods incorporated into the top of the grave, and simply alerted the body snatchers to the risk. Tripwires would then be removed and replaced as a matter of course, with loved ones would be none the wiser.

But put a cemetery gun in front of a non-professional and things could be very different as students discovered in 1823 when they were peppered with shots in the leg in an undisclosed churchyard in London.

Elsewhere in London, things were turning out much better. The sexton of St Martin in the Fields, deciding to take things a step further with the cemetery gun design, devised the ‘ultimate’ cemetery gun when he attached a number of gun barrels together to form a magazine.

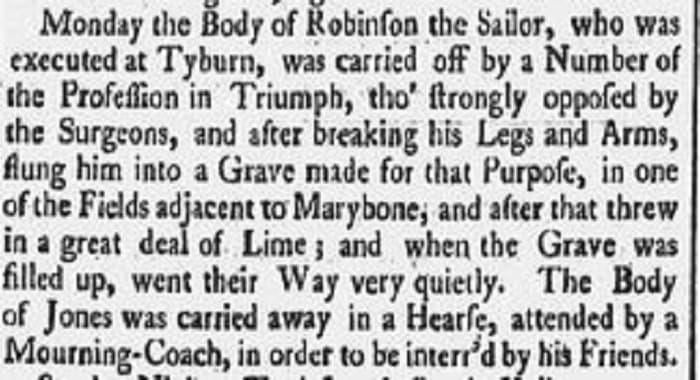

On a cold night just before New Years Eve in 1817, the contraption probably put the fear of God into everyone when ‘a tremendous report’ was heard across the graveyard. Although no-one was killed under a tirade of bullets, a body snatcher’s hat was found with only one bullet hole in it, the bullet still presumably lodged in his head.

The Man-Trap

Sticking with the loose theme here of turning anti-poaching devices into body snatching prevention, I also want to share with you the deadly man-trap.

The man-trap works exactly as you’d expect. A metal snare is hidden beneath the soil that when stepped on would release the spring and secure around the foot of the intruder.

There’s a fantastic example of this piece of kit at the Beamish Open Air Museum in Tyneside, UK, although it is displayed with its intended use in mind.

I have only found one instance of a body snatcher linked to a man-trap, and I expect there to be more hidden somewhere out there, but the one that I want to share here is in relation to two very brazen body snatchers, Duffin & Marshall.

In the winter of 1817, the church of St Mary’s, Lambeth were looking to hire men to watch over the graves in the churchyard. It would be a hard task, for the churchyard was frequently visited by the resurrection men and it was hoped that having a more permanent watch in place would combat the problem.

Unbeknown to the church, the men they hired were already seasoned body snatchers and it was soon discovered that despite having a dedicated watch on-site, not a night went by without a body being snatched from the grave.

With no fewer than five burials having recently taken place, there were certainly supplies to be had and with honest men from the parish mounting their own watch, it wasn’t long before the body snatchers could be heard going about their work.

With two man-traps concealed under specific graves quickly disarmed, it wasn’t until the body snatchers struck the coffin lid with their shovels that the men decided to act.

Duffin and Marshall failed to get away with their plan and each received a two year sentence in the county gaol.

Failing To Bury The Dead

Or shall I say, failing to bury the dead in a churchyard.

The theory behind this prevention method is pretty obvious. Bodies were stolen from graveyards, so, if you buried your loved one elsewhere, they wouldn’t get snatched, right?

Well, yes. And to be honest, it’s probably one of the most effective and simplest methods of body snatching prevention out there.

It’s been used a number of times in various places across Britain and this is just one of my favourite finds in this category.

In 1841, long after the threat of the resurrection men had passed, a man by the name of Mr Hedges was in his garden when he noticed that the ground dipped somewhat in the middle. Naturally curious he got to work with his spade.

It wasn’t long before he reached a homemade coffin that contained the body of a young female. The coffin had been thrown together with some old window shutters and placed there during the height of the body snatching era by the girl’s father, a guard on the Express coach which operated between Hull and London.

The man had been witness to so many cadavers being transported to and from the Metropolis that he was determined his girl would remain put. He even went so far as to arrange a mock funeral in the local parish church so that it would be unknown that his daughter was buried in safety in his back garden.

Sure enough, or so the report goes, an attempt was made on her grave the night she was ‘buried’ proving once and for all that he’d done the right thing.

After Mr Hedges had found the coffin in his back garden, he had the homemade coffin re-interred in the safety of the parish church, confident that the threat of body snatching was long gone.

Strange Forms Of Body Snatching Prevention

My final section in this post is a series of the more unusual forms of body snatching prevention that I’ve come across that don’t really fit into any category at all.

My first strange find has to be the most random account that I’ve come across yet but that’s not to say that it wouldn’t have been effective.

Sulphuric Acid

I don’t have much information about it I’m afraid other than it happened in Yorkshire c.1830 and it was but a mere suggestion. The small snippet found in the York Chronicle suggested that sulphuric acid be poured over the body prior to burial to make it unsuitable for medical research.

This would certainly have done the trick and I suspect that the author got the idea after reading accounts where bodies were covered in quicklime after burial. It’s the only snippet I’ve found on the case, but I keep it as a reference should I find anything more.

An Adapted Coffin No. 1

This next case happened in 1823 and involved the burial of 19 yr old Ann Milsome. Fearful for the protection of his daughter’s body, Mr Milsome, a coal merchant from Newbury in Berkshire, devised a contraption that was attached to the coffin and lowered into the grave with it.

Found in Jackson’s Oxford Journal, the device is perhaps best described directly :

‘The coffin, which contained the body, was chained to a stone let into the earth some feet underneath the bottom of the grave, and fastened by means of spring bolts…’

Sounds like a cross between a mortstone and a mortsafe with a regional twist. Not sure if it worked, but I bet it made Mr Milsome feel at ease.

Adapted Coffin No. 2

A similar idea was reported in the papers two years later. Building on the idea of the Northumberland landowner above, once the head of the coffin had been inserted into a recess in the grave, iron stakes were then driven down each side of the coffin and an iron bar secured over the lid.

Again this is an adaptation of the mortsafe, where iron bars are secured around the coffin holding it in place.

My final prevention method for this post happened in February 1828 and involved the wife of a stonemason, Mr Dowling, who lived in the parish of St Luke’s, Exeter.

When Mr Dowling’s wife died during childbirth he was determined to keep her away from the hands of the resurrection men and so he decided to refrain from burying her, and their deceased child, until March, just a few weeks away.

His reasoning was that come March, their bodies would be unfit for the anatomists and the body snatchers would leave them alone.

Although just to be doubly sure that nothing untoward would come of his departed family, Mr Dowling laid his wife and child to rest in a leaden coffin which was subsequently enclosed in two wooden ones.

When the report was printed in the newspaper at the beginning of February, Mrs Dowling and her child were said to still be in the house where they had died.

Taking Things Further

[1] I am indebted to Fife County Archaeologist, Douglas Spiers, for the information about the St Andrew’s and Monimail coffin collars and for discussing with me their possible adaptation from punishment jougs which were widely used in kirkyards throughout Scotland.

[2] I carried out extensive research when I wrote my book ‘Bodysnatchers: Digging Up The Untold Stories of Britain’s Resurrection Men’ and so used some of the cases for this article. This particular article about the coffin collar found in Glasgow comes from the Glasgow Free Press, July 1833. As always, I use The British Newspaper Archive (£) when carrying out my research.