Body Snatching In Lasswade Old Kirkyard, Midlothian, EH18

Have you ever noticed that most of the stories told about body snatching often only talk about men?

Well, there’s a good reason for that, mainly because most body snatchers were men, it wasn’t really an occupation that women seemed to take up for some reason.

But have you ever wondered what role females played in this macabre trade?

As a general rule, the wives or girlfriends of body snatchers often took up the role of ‘scout’ or informant. Many befriended sextons or visited workhouses, pretending to be long lost relatives, just so they could get their hands on cadavers and have an idea of who was being buried and how deep.

But what about the women who did a little bit more than this? What about the women who decided to be their own boss so to speak?

The Story of Helen Miller

Take, for example, Helen Miller, described by some authors as a ‘she-devil’ who in January 1829, suddenly found herself without money for food and other basic necessities.

Helen, a widow by the time her story plays out, was once married to a bodysnatcher; a man now locked up in gaol for stealing a cadaver from the graveyard in Lanark, 36 miles from where our story takes place, in the direction of Glasgow.

Helen was an enterprising soul, her drive for drink making her come up with rather an ingenious plan, in what was known to be a very lucrative sideline.

She simply planned to contact the resurrection men in Edinburgh and tell them where and when a fresh cadaver was available and get paid for providing the information. Simple.

And so it was that Helen Miller, neé Begbie turned informant.

Edinburgh’s Resurrection Men

Her first target was known counterfeiter and thief, James Gow. The 25-year-old, by all accounts, sounded as though he’d turn his hand to anything.

So when Helen gave him information as to where he could find a cadaver and a fresh one at that, he wasn’t going to miss the chance of earning a quick buck.

The going rate for fresh subjects was £10, at least, that’s what Dr Knox was paying.

And so, while Burke and Hare were contemplating their fate after their killing spree on Edinburgh’s streets had come to an end, James Gow grabbed his painter friend and sidekick James Hewitt and made a beeline for Lasswade.

The ‘Old Kirk’ of Lasswade

The target of Helen’s enterprise was a town in the beautiful Midlothian countryside called Lasswade.

Once famed for strawberries, papermaking and carpet manufacture, the tranquillity of this small town was about to shatter forever.

Dedicated to St Edwin, by the time 1829 had rolled around, the church in Lasswade, having closed its doors in 1793, was already a ruin.

Known locally as the ‘Old Kirk’, interments were still being made in the kirkyard and week after week, the parish dead would be placed carefully among the gravestones.

With a congregation of over 1000, you can perhaps see where Helen Miller was going with this.

One key feature of the ‘Old Kirk’ however, was a three-story bell tower that was used by the watch when they were keeping an eye out over the graves for resurrection men.

Although now gone, (it actually collapsed during repair work in 1866) the watchtower wasn’t used the night Helen Miller started to put her ‘business’ (and I use the term loosely) into operation.

In fact, she’s said to have informed the resurrection men that the coast would be clear and that ‘there was no watch’ on the night of the snatchings.

Preparing For The Raid

It’s not every counterfeiter and painter that already has their own equipment for extracting cadavers, and so before leaving Edinburgh, Helen’s first customers, Gow and Hewitt, had to find some equipment.

They paid a visit to anatomist John Lizars, offering him first refusal of the cadaver if he’d give them some money for a spade.

Now, the criminal fraternity isn’t really known for keeping their word and so it is perhaps of little surprise if I tell you that Lizars refused to help on this occasion.

He was, however, still interested in purchasing a cadaver once they’d got one out of the ground and would end up paying 10 guineas for one of the adult corpses taken when the pair returned from Lasswade.

This was of little, if any, help to the two James’ set off to try their luck with Thomas Aitken instead, surgeon and lecturer at Surgeon’s Square. Again they were rebuffed.

There perhaps wasn’t an anatomist in the whole of Edinburgh who would be stupid enough to give a body snatcher money BEFORE seeing the corpse, he was going to have to try to find his own spade.

As luck would have it, however, the enterprising Helen came to the rescue and offered the bodysnatchers the use of one of her spades when they arrived in Lasswade.

A Frenzy In Lasswade Kirkyard.

The first cadaver that Helen informed Gow of was that of a female corpse. Highly prized amongst surgeons and guaranteed to bring a fair price and two days later, Gow and Hewitt turned up with the body of Joan Swan stuffed into a sack at the backdoor of Surgeon’s Square.

As news filtered into Edinburgh about the availability of cadavers, Gow and Hewitt started to make their way back and forth to Lasswade.

In her desperation, either for a drink or some other commodious item, Miller had somehow worked her way around a number of resurrectionists in Edinburgh. One by one, telling them of the bounty available in Lasswade.

When Gow and Hewitt returned to the site, they weren’t the only ones there hoping to make a quick profit.

By the time Helen has finished spreading the news of the spoils to be had on the outskirts of town, a total of eleven body snatchers and surgeons were involved in the plot to strip Lasswade clean of its dead, and amongst them was notorious Edinburgh bodysnatcher Andrew Merrylees.

Edinburgh’s Notorious Andrew Merrylees

Andrew Merrylees alias Lees is perhaps more famously known by his nickname ‘Merry Andrew’ and is one of the more famous of Edinburgh’s resurrection men operating at this time.

Originally from the country, Lees was the head of a small band of resurrection men who often descended on Edinburgh’s kirkyards for the dead.

A regular on the ‘anatomist’s circuit’ Andrew Merrylees, a bodysnatcher known for not taking any cheek from his fellow gang members, was also known to be providing cadavers to the famous Dr Knox, the anatomist linked to murderers Burke and Hare.

Trial and Imprisonment Of Edinburgh’s Bodysnatchers

It wasn’t long before the snatchings at Lasswade were discovered and Helen quickly went out of business.

All of the eleven bodysnatchers – and let’s be clear here, the group also included some anatomists – were charged with violating two graves in Lasswade.

Accounts mention three cadavers in total being sold to the anatomists that January in 1829, one we’ve already seen went to Dr Lizars for the sum of 10 guineas.

Now incidentally, it is said that he then later sold this on to another anatomist for a further 5 guineas. Not a bad turn around some might say.

The cadavers taken at the beginning of 1829, do have names, they were John Braid, Joan Swan, mentioned above, and the body of an unknown child.

I’ve not yet been able to find information about this last cadaver, but hopefully, something further will turn up as my research continues.

When the trial was finally held in July, three of those accused were immediately outlawed for not appearing, one of these included Andrew Merrylees. The instigator of the whole affair Helen Miller wasn’t prosecuted, but that still left a number of individuals to be tried and their fate turned out to be very different to the others.

The anatomists involved weren’t prosecuted and the only men punished for their part in the Lasswade raids were three body snatchers by the names of Kerr, Barclay and Cameron.

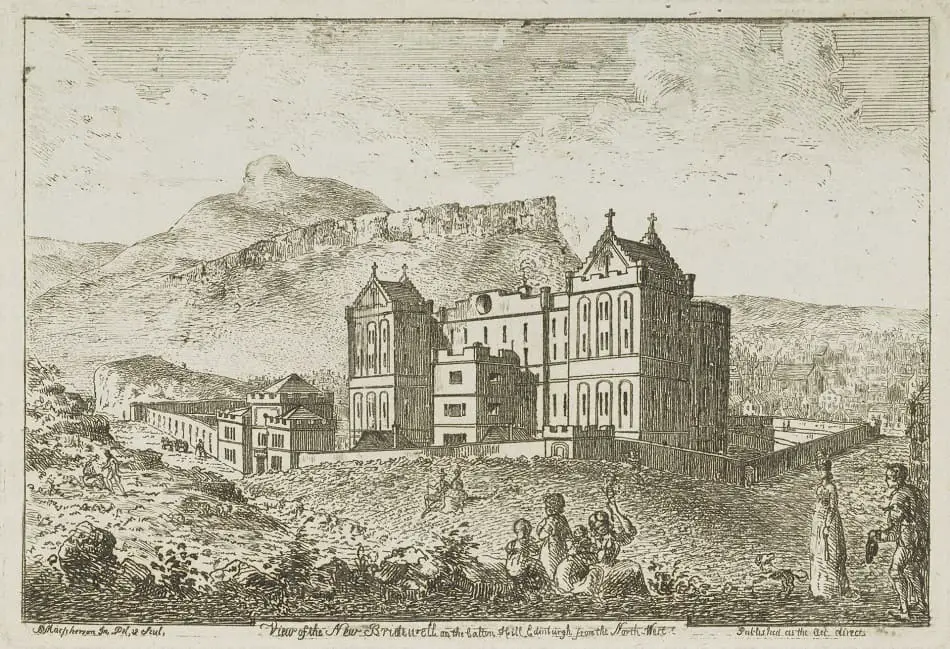

John Kerr, a known resurrectionist on the streets of Edinburgh, was sentenced to nine months imprisonment with hard labour in the Bridewell on Calton Hill. He was to be joined for six of those months by James Barclay and George Cameron.

The Fate of James Gow – Counterfeiter, Thief & One Time Body Snatcher

Having had a lucky escape at the trial in July, Gow had learnt nothing from his recent brush with the law.

One year later he was once again being accused of stealing a cadaver but this time, things were about to take a slightly different turn.

Having previously made a deal to acquire a cadaver from lodgings in Old Assembly Close; a narrow lane tucked just off the Royal Mile in the heart of Edinburgh City, on arrival Gow discovered that the door was locked.

Instead of returning at a later date, Gow, together with a new accomplice Daniel Grant, broke down the door, and immediately escalated their crime from misdemeanour to a felony.

Some accounts of this episode say that Gow was transported for his crimes but I don’t believe this to be true. Instead, I believe he was sentenced, along with Daniel, to nine-month imprisonment in the Bridwell on Calton Hill.

The Aftermath of The Body Snatchers

Take a trip to Lasswade today and you’ll find remnants of its body snatching past. Fear of a visit from these ‘ungodly men’ had brought a genuine fear into the lives of the inhabitants of Lasswade and this can be seen throughout the ‘Old Kirkyard’ today.

As you walk into the site, look up and then over to the left. The caged lair you see is in the Calderwood Enclosure, lying in the Calderwood of Polton aisle of the Old Kirk.

Its iron-barred roof would have created a barrier between the body snatcher and the anatomists’ table. If you’re lucky, the door to the lair may be unlocked, I find these places incredibly eerie when walking inside.

Laying on the grass near what is known as the Eldin Aisle is a large lump of rock, properly referred to as a mortstone. This would have been shared amongst the parish and placed over the top of the coffin until the corpse inside was no longer useful to the anatomists.

To get a better understanding of mortstones, why not take a look at my other post ‘Mortstones: Protecting Yourself From The Resurrection Men’

The final type of body snatching prevention is sadly no longer here for it collapsed in 1866. In the former bell tower to the original kirk was a watch house, taking up the lower floor of this three-story high structure.

It would have been there in 1829 when the site was being raided by Gow and his fellow body snatchers and it remains a mystery why no watch was on duty that January in 1829. Even Helen Miller mentioned that the coast would be clear for ‘there was no watch’ – a grave mistake indeed.

Taking Things Further

[1] I have already referred to two books which also mention this case, Norman Adams ‘Scottish Bodysnatchers’ and Geoff Holder’s ‘Scottish Bodysnatchers: A Gazetteer’, both of which are excellent.

I have built on this case but my research is by no means complete. Tracing a body snatcher is a little like tracing your own family history, sometimes the information is forthcoming, other times it’s like pulling teeth trying to piece the information together. I hope to build on this someday.

[2] Canmore, the Historic Environment website has some terrific images of the tower at Lasswade Kirk dating to 1839, a view well known to the resurrection men targeting the site. One drawing, showing the south view of the church along with the tower titled ‘South view of Old Church at Lasswade, sketched from nature by Alex. Archer. 1839’ is a great example of what the site would have been like.

[3[ Lasswade District Civic Society website helped with references to events and statistics in order to piece together an image of Lasswade when body snatchers would have been working the area and shipping cadavers back to Edinburgh nine miles away.

[4] According to the information sign as you enter the kirkyard, provided by the Lasswade District Civic Society (see above), restoration work carried out within the enclosure (date unknown) unearthed a number of 16th century bones that had been trepanned.

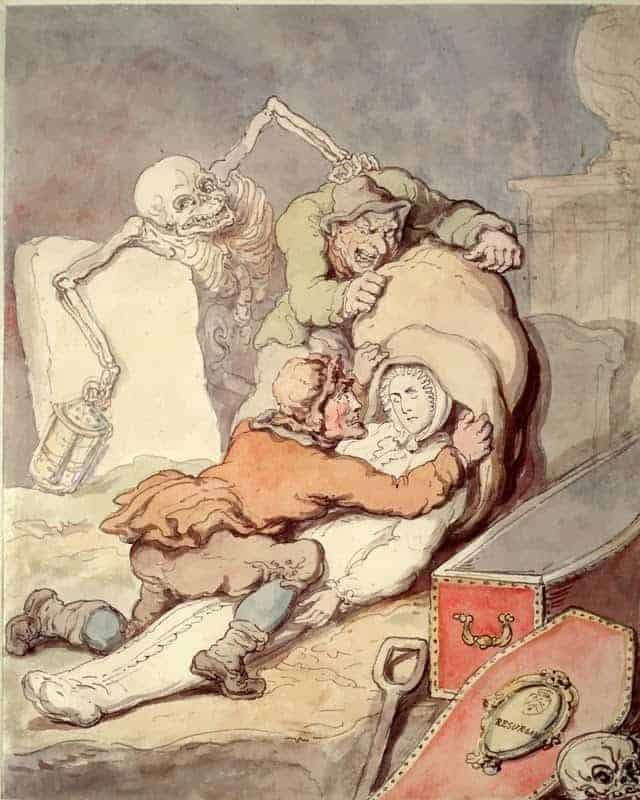

![‘[A] Miraculous Circumstance’](https://mymacabreroadtrip.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Rawlinson-Resurrection-Men-via-Wellcome-Library-Diggingup1800-768x934.jpg)