Why Did Anatomists Hire Body Snatchers? | The Real Reasons

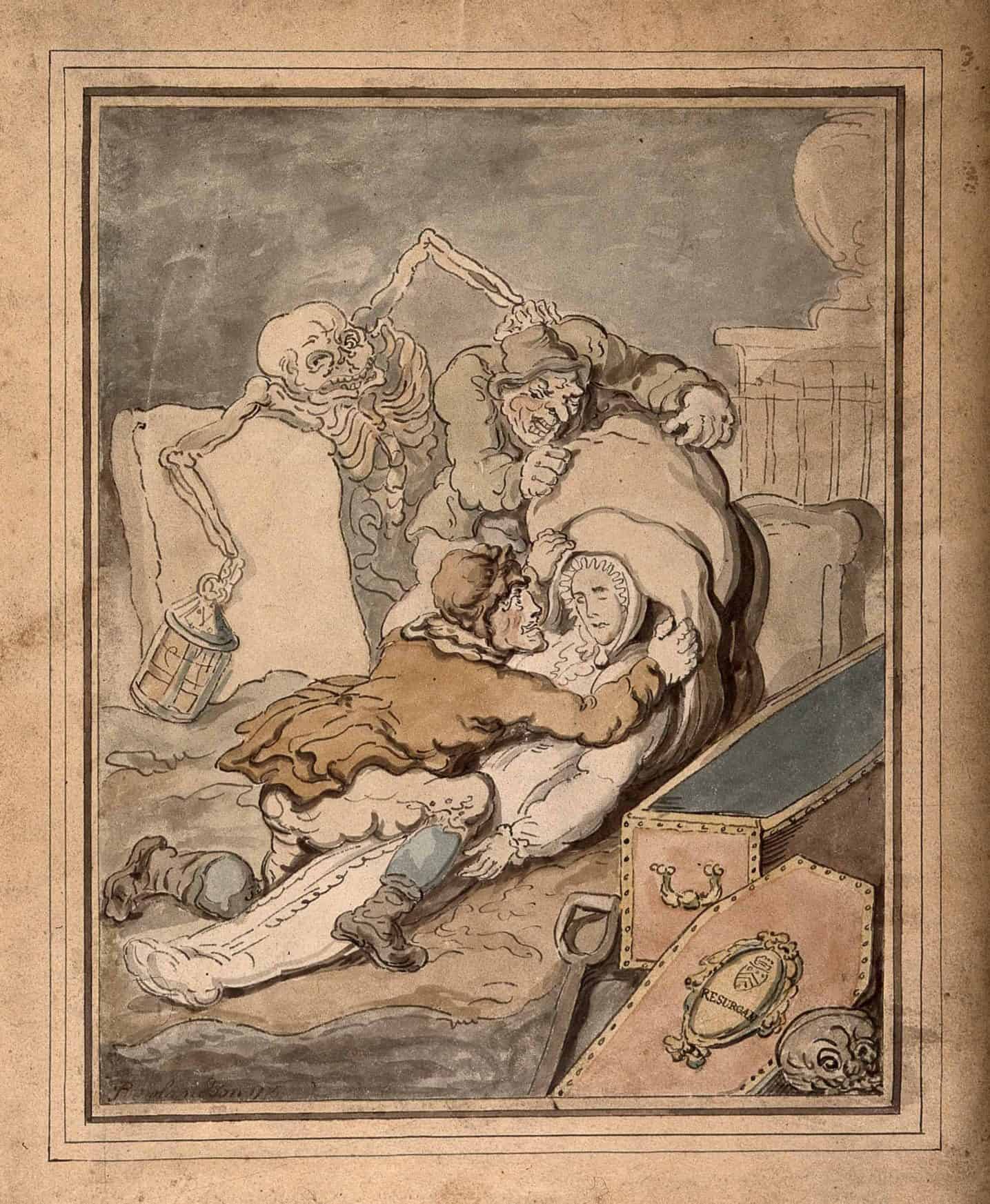

In a world where character and status meant everything, by the late Eighteenth-century anatomists of Georgian Britain were no longer prepared to risk their careers grubbing around in mud to obtain a cadaver for the dissecting table.

With parishioners being on high alert over their recently buried dead, and corrupt officials becoming wary of strangers offering to buy a corpse if they’d help them extract one from the grave, what was it then that eventually forced anatomists out of the graveyard and back into the dissecting rooms?

There are a number of factors that saw anatomists retreat from the graveyard and back into the dissecting rooms. With the stigma surrounding body snatching increasing towards the end of the eighteenth century, together with a change in the law in 1788, meaning that the practice was now classed as a misdemeanour, fewer men were willing to risk their character and future careers obtaining cadavers when professional body snatchers were waiting in the sidelines to take over.

In this post, I want to look at why anatomists and medical students would eventually prefer to keep out of the graveyard, passing the task of stealing cadavers onto a professional set of men who would lay down the foundations for one of the most macabre periods of British medical history to date.

Body Snatching In The Mid Eighteenth Century

I guess no-one had really thought things through when they started offering an increased number of anatomy and dissection lectures to a captivated student population in the mid-eighteenth century.

With student numbers, as a whole still being relatively low, the needs of the anatomy schools could be met fairly simply. When a cadaver was needed students and anatomists would simply go out and obtain one themselves. Although they had little regard for the corpse or the graveyard, public awareness of the practice meant that, for the time being at least, they could carry on pretty much undetected.

The passion and drive of anatomists such as John and William Hunter[1] and Sir Astley Paston Cooper, surgeon to George IV and one-time student himself of John Hunter’s, meant that not only were they driving up the student population in the medical sector, but they were also ensuring that the legally available supply of cadavers was falling woefully short of the amount needed to keep this new expanding student population happy.

Early Anatomy Lectures

When William Hunter’s private anatomy school in Great Windmill Street opened in 1746, it offered students the unique opportunity to study anatomy in the ‘Paris Manner’ – that is for students to finally be able to cut up a cadaver all of their own.

Early anatomy/dissection lectures meant students were forced to share old body parts picked out of tubs full of brine -already dissected and mutilated.

Or to watch blindly as a demonstrator carved open a cadaver laying on the wooden dissecting table in the centre of the theatre, the surgeon explaining body parts from his notes.

Arrive late to class and you were destined to either spend the whole of the lecture in the upper levels of the dissecting room theatre or the body part you’d fished from its briny home was nothing more than a few decomposing sinewed strands holding it together.

As the number of private anatomy schools started to increase – there were twelve independent schools in London alone by 1826 – the six legally available cadavers were becoming something of a joke.

To ensure a school’s success – and to increase its fame and credibility- the promises of providing cadavers for the dissecting table had to be met somehow.

The Beginning Of Body Snatching: When Doctors & Students Stole Cadavers

As with any new venture, things are often manageable in the beginning, and so was the case with medical study in mid- Eighteenth century Britain.

While student numbers were still relatively low enough – only 54 students in Glasgow in 1790[2] for example – and before parishioners had become attuned to the fact that the local medical fraternity were rifling the graves of their loved ones, the students and anatomists would head out stealing cadavers themselves.

History is awash with stories of the medical fraternity violating graves. Their need was small and so they would go out as and when cadavers were required.

Small groups of students, around say three in number, would target predominantly inner-city graveyards and choose what appeared to them to be the freshest burial.

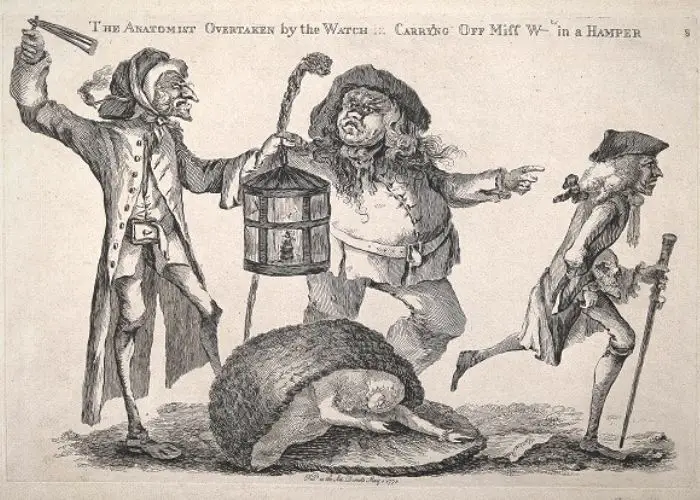

The problem with student body snatchers however is that there was no real technique or finesse in their extraction methods.

Take for example the snatching of Mrs Janet Spark in 1808 from the coastal graveyard of St Fittick’s in Aberdeenshire.

Janet had been roughly taken from her grave a few days before Christmas Day and the students involved had left her grave clothes strewn about the graveyard and the lid to her coffin broken to pieces on the grass.

When the professionals were targeting graveyards in the early nineteenth century, they made dam sure that they left no trace of being there so that they could target the site over and over again.

In fact, they were that good that we know of one site where the snatchings were so prolific that when it was discovered that body snatchers were targeting the area, there were only 21 coffins left untouched in the whole of the graveyard, the rest having been broken in to and the cadaver removed.

Student Body Snatchers

Edinburgh and Glasgow, along with Aberdeen whose students had formed a Medical Society in 1789, were perhaps more ardent snatchers than their fellow students in London.

In 1711, Edinburgh’s townsfolk were already complaining bitterly to the Incorporation of Surgeons as graves were continually being violated in the famous Greyfriars Kirkyard in the heart of the city.

Ten years later, in 1721, when students studied at Edinburgh University under the famous Alexander Monro Primus, the students were so active in the city’s graveyards that a clause had to be inserted into their indentures by the College of Surgeons forbidding them to carry out this practice.

Things had got so bad in Perth, further north, that in 1718 three students, having been caught with the corpse of John Taylor were fined £100 Scots Pounds and ordered to rebury his body in the grave he came out of!

But student body snatchers were much more careless.

They seem to have had no regard for those who had been buried or for their loved ones left behind. Coffins would be pulled completely from their graves, burial shrouds and caps were removed from the corpse and left strewn across the graveyard for all to see – there was no consideration that perhaps they should have been keeping quiet about what they were doing.

But despite these warnings, and the public becoming increasingly more aware of the graveyards being targeted, both in Scotland and England, the violation didn’t stop and it became increasingly risky for men with such standing to continue pilfering graves.

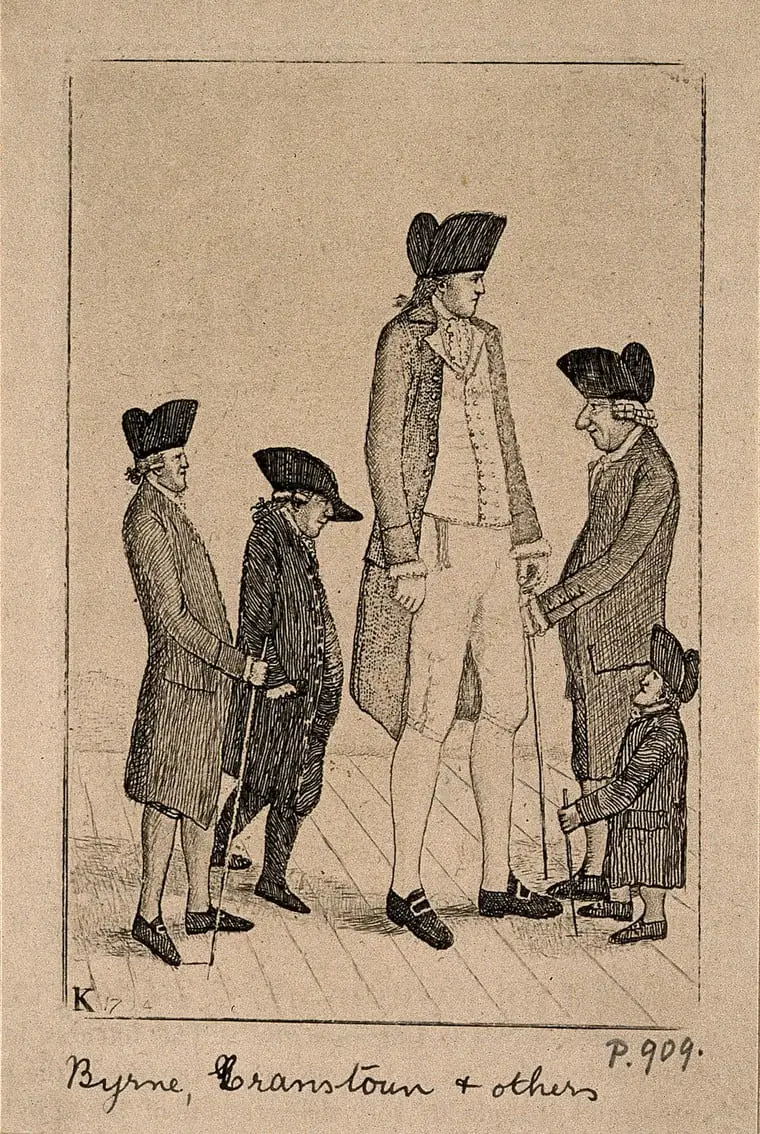

The Snatching Of The Irish Giant, Charles Byrne

The most famous snatching carried out by anatomists is that of the Irish Giant, Charles Byrne in 1783, better remembered as the snatching of the 7ft 6” (2.3m) tall Charles Byrne.

Charles Byrne had arrived in England from Ireland and caused such a sensation that William Hunter probably had designs on his skeleton long before the man even became sick. It is said that he was that tall that he startled constables in Edinburgh by lighting his pipe from street lamps, drawing a crowd around him wherever he went.

Byrne was 22 years of age when he passed away in his lodgings at Cockspur Street, Charing Cross.

He knew that his body was coveted by the Hunter brothers and after begging his friends to promise that they would bury him in a lead coffin far out into the English Channel, Byrne eventually slipped away.

But his friends were lured by the vast sums of money, £500 to be exact (about £43,000 in today’s money) and after Hunter had begged and borrowed the desired amount, the body of Charles Bryne was his.

A mock funeral did take place – which is written in Wendy Moore’s The Knife Man – Byrne’s friends transported a leaden coffin to Margate on the 5 June, chartered a boat and slid the coffin over the side and into the sea.

But Byrne was instead at William Hunter’s new home in Castle Street, waiting to be dissected.

In 1788, however, things were about to change.

The Crime Of Body Snatching Becomes A Misdemeanour

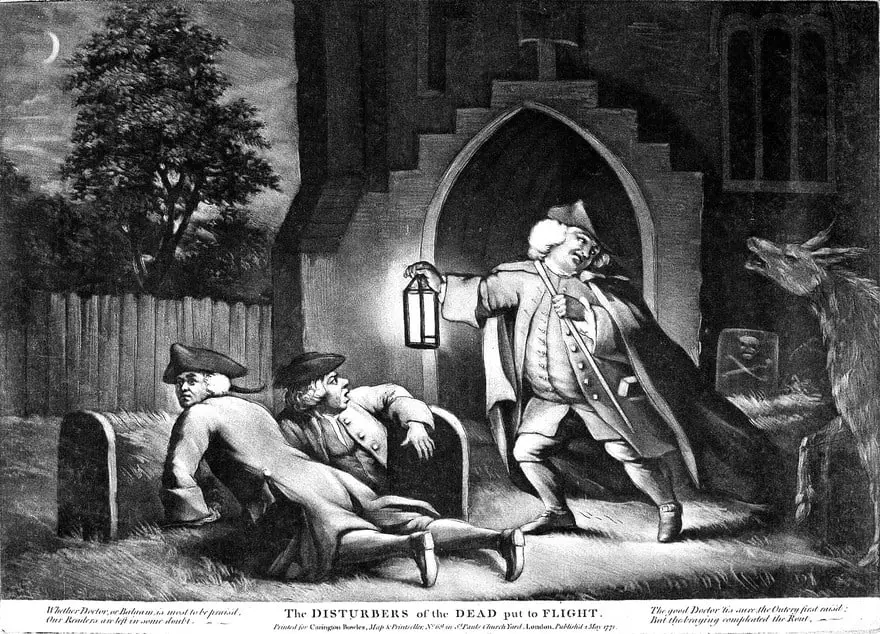

If you got caught stealing cadavers before 1788, chances were that your sentence would be very lenient indeed.

But soon after this date, things changed and a swift wrap on the knuckles by a forward-thinking Magistrate was one thing, but a fine and a possible prison sentence were another.

In 1788 – the same year in which New York Hospital experienced an anatomy riot lasting for two days – a famous case, Rex V Lynn, was brought to trial at the Court of King’s Bench and forged the path ahead for the emergence of professional body snatchers.

It is here that it was agreed that a cadaver didn’t belong to anybody, a fact that those pilfering graves were already acutely aware of.

But what was also decided in the courtroom that day was that graverobbing – that is, to steal a dead body – was contra bonos mores, in other words morally wrong and that a suitable punishment should be applied to those caught partaking in the practice.

Lynn was about to make body snatching history and be the first person to be charged for this new misdemeanour having been accused of stealing the body of a female from the parish graveyard of St Saviour’s churchyard in London.

As there was no precedent for this crime, imprisonment wasn’t really an option at this stage and so a fine of five marks* was issued instead.

The Rise Of The Professional Body Snatcher

With courts starting to listen to public disquiet over the actions that the students and anatomists were taking against their dead and their graveyards, it was slowly becoming less attractive to go out foraging for dead yourself.

The fines, although they may have started off small, quickly became pretty steep. Students were regularly fined £10 or more for their part in raids.

John Davies, a student at Dr Moss’s Dispensary in Warrington, Cheshire was fined £20 in 1828 for stealing the body of Jane Fairclough from Heathcliff Burying Ground – the fact that she discovered stuffed into a hamper may also have something to with the hefty fine.

Four years earlier in 1824, medical student Thomas Thompson was actually sentenced to three months of hard labour and a 6d fine for stealing Elizabeth Headley from her final resting place in Sunderland. The poor girl was actually found by her father, all packed up ready to be sent to a Doctor in Leith, Edinburgh.

Students and anatomists were no longer willing to risk paying a fine or tarnishing their character when there were men waiting on the periphery to do the job for them.

Bribing sextons was getting harder. They no longer trusted random strangers who walked up to them offering money if they’d help secure a cadaver fearing that it was probably a trap set by parishioners in which to catch them out.

Medical schools were also increasing the punishments that they were giving to students should they be caught involved in the macabre practice, with Glasgow University promising to ban any student involved in body snatching after 1813.

It just wasn’t worth the risk any more and gradually student and anatomist involvement in body snatching began to wane.

The Professional Body Snatcher Takes Over

With the professional body snatcher came a series of demands that perhaps the anatomists had not even dreamt of.

Not only were a very strict set of guidelines followed but a new concept was introduced into the process.

Opening and finishing money, a term never before heard of was demanded from one of the most prolific and successful gangs operating within London.

This money was used to grease the palms of corrupt officials – sextons, watchmen and even constables – so that easy access into the city’s graveyards and beyond would be granted and little of nothing would stand in the way of procuring a cadaver.

Techniques for extracting a cadaver from its grave were finely tuned so much so that a graveyard could be worked for months without anyone becoming suspicious.

The process was coming a full circle. Once again the sextons and officials were being lured into the darker side of graveyard work, the pay received from the body snatcher fueling the greed of some to such an extent that they in turn would be forced to leave their jobs and become full-time resurrection men themselves.

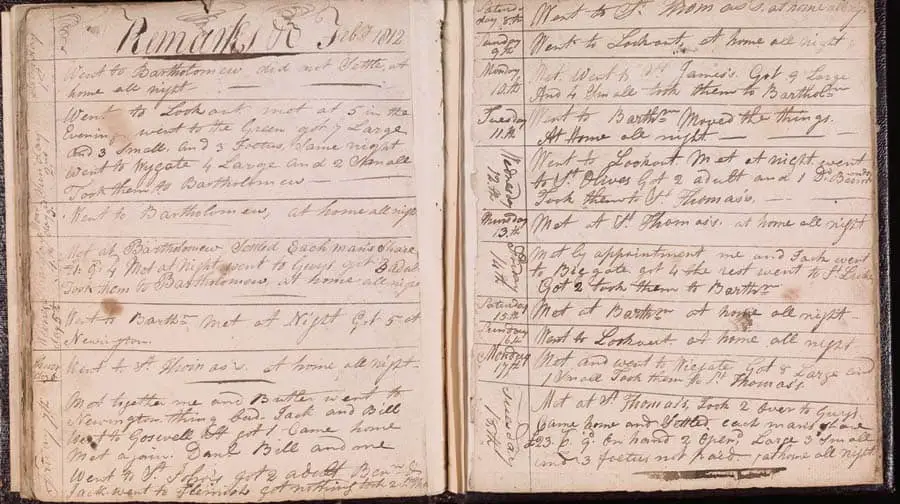

In order to appreciate the process and prolific nature of the body snatching business, we are extremely fortunate to have a diary, which was kept by a member of arguably the best body snatching gang to date, The Borough Gang’.

The Diary, known universally as ‘The Diary of A Resurrectionist’ was written by gang member Joseph Naples between November 1811 – December 1812 and consists of only 16 pages.

It is perhaps the most informative account that we have of the dealings of the resurrection men at a time when the professional body snatcher had only really fully emerged.

The Diary records the money made, the number of cadavers stolen each night and the names of the doctors who bought them. It truly is a fascinating insight into the macabre underworld of Georgian Britain [3]

And Finally…

The temptation was still too great for some students and anatomists, however, and as the years ticked by the curiosity of dissecting a human cadaver got the better of many individuals.

Students were forced to leave the realm, only to be pardoned at a later date when fully qualifying as a doctor. Others, like Robert Nesbitt, The Younger, accused of stealing the corpse of Christian Ross in 1792 were never caught or they simply absconded, never to return.

And then of course there were the extreme cases.

A whopping £100 fine was slapped onto Surgeon William Cook in Exeter in 1826 for implicating the local sexton in snatching the body of Elizabeth Taylor but his case is unusual.

And so it is, that with nearly 100 years of bumbling and making a nuisance of themselves we may not have had the professional body snatcher enter the pages of history, and for that, I perhaps alone am grateful, because without the students and anatomists I would never have been able to study the macabre underworld of Britain’s body snatching fraternity.

Taking It Further

*This figure of Five Marks, already converted to £2 6s 8d by writer Hubert Cole in his book mentioned below can be calculated to be the equivalent of around £255.

I could recommend most of the books that I’ve read on body snatching for this area of the subject and you may enjoy seeing some of my recommendations on my resources page, but for this post specifically, I’d probably choose from the following three books on the subject.

[1] Wendy Moore’s ‘The Knife Man’ (AbeBooks.co.uk) is a superbly written biography on the life of Wiliam Hunter, the anatomist who opened a private anatomy school in Great Windmill Street, London and who stole the body of the Irish Giant, Charles Byrne.

Moore’s account of Hunter’s life sucks you into Georgian England and is a compelling account of not only his work in medicine but also of his private life and involvement in body snatching,

Martin Fido’s ‘Bodysnatchers: A History of The Resurrectionists’ (AbeBooks.co.uk) was one of the first books on body snatching that I ever bought and I dip into it still nearly every day. I love Fido’s ease in writing about this topic and find that he often has something different to say from other authors.

His book will always be in my ‘Top 10’ of body snatching books along with my next recommendation from Hubert Cole.

Cole’s book ‘Things For The Surgeon’ is a classic and just like Fido’s work, I dip into this one regularly. The price of Cole’s book is now extortionate, at my last check, it was nearing £800! I’ve provided the link for the book on Amazon.co.uk should you wish to check it out for yourself.

[2] I carried out a lot of research for my book ‘BodySnatchers: Digging Up The Untold Stories Of Britain’s Resurrection Men’ (Amazon.co.uk) and so I often refer back to my own work for stats and specific body snatching cases.

For the stats regarding student numbers etc. I used the fantastic work by Dr Ruth Richardson ‘Death, Dissection and the Destitute’ which should be on anybody snatching fan’s bookcase.

[3] For a FREE searchable copy of ‘The Diary of A Resurrectionist’, you need to access The Project Gutenberg website.