St Mary’s Church: Whitkirk, West Yorkshire

Five year old Hannah Heesom died right in the middle of the body snatching era.

In fact, her father buried her in St Mary’s Church, Whitkirk, on New Year’s Eve 1828, only a few short weeks before the notorious William Burke was due to hang.

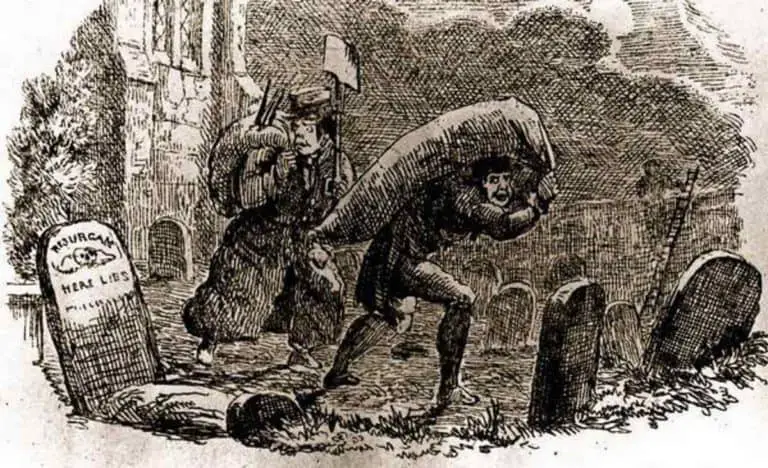

Body snatching would have been on the minds of most parishioners then, especially if you were burying a loved one.

Your main hope was that they’d remain in the ground long enough for the resurrection men to pass them by and that the worms got them instead of the anatomists.

Burying Hannah

As the year 1828 came to a close, murderers Burke and Hare had just come to the end of their murdering spree and in three days’ time, Burke would be giving his first full confession of the murders.

Hannah’s father Thomas Heesom (some accounts say Ralph), therefore, had every right to be jittery about burying his daughter.

There was no watch in place at Whitkirk, nor was there the use of a mortsafe, and Hannah’s father doesn’t appear to have been able to have afforded such items even if they had been available and so put his faith in the hands of the sexton when it came to protecting his daughter.

Protecting the dead when you were poor required some simple thinking. Obvious deterrents, that were readily available and that would either fit in with the family budget or could be sourced for free.

There were many measures that Thomas could have chosen to protect his daughter’s grave.

A pile of sticks or stones on top of her grave perhaps or would something incorporated into the soil work better for Hannah?

There were several alternatives he could have used, you can read about them in a blog post I specifically wrote about body snatching prevention for the poor but in the end, Thomas chose to use straw.

Protecting Hannah

On the day of Hannah’s burial, her father had given strict instructions to the sexton of St Mary’s to mix layers of straw in with the soil when filling in Hannah’s grave.

The instructions were quite simple, layer upon alternative layer of straw and soil. Putting his trust in the sexton that he would fulfil a grieving man’s wishes, Thomas returned home alone.

Unfortunately, these simple instructions were ignored.

The straw Thomas intended to be missed through with the soil when filling Hannah’s grave was simply placed in one heap on top of the coffin before any soil had even reached the end of the spade.

Thomas’s request to dig a deeper grave for Hannah was also ignored.

The Taking of Hannah Heesom

Less than 24 hours after being interred in the ground, Hannah’s body was stolen.

If the Sexton had listened to Thomas Heesom that day, Hannah may still be lying in her grave.

As it was, the soil barely had time to settle before body snatcher Thomas Brown was removing Hannah’s small body from the grave

‘taking it out of the coffin and tying it up in his shirt…’

Despite appearing to not have the means of providing more reliable body snatching prevention, when Mr Heesom learnt that his daughter had been taken he offered a reward of £10.

This however did not go quite to who he’d have imagined.

The Trial

It didn’t take long for authorities to find the man responsible for taking Hannah and we have ‘fellow’ body snatcher William Yeardley to thank for that.

He double-crossed his comrade Thomas Brown in a bizarre twist that demonstrates just how unscrupulous body snatchers actually were.

Novice body snatcher Thomas Brown was a labourer/bricklayer by trade and this was to be his first foray into the world of body snatching.

He wasn’t very good at it by all accounts and left evidence strewn across the graveyard for all to see. He perhaps would have been arrested eventually anyway.

At the January Sessions for the West Riding of Yorkshire, the principal witness was fellow body snatcher William Yeardley. He stated that Brown had been so unprofessional during the ‘job’ that he’d ruined any chances of any other resurrection men using the site for a least a year.

A collective sigh of relief must have washed over the court room that day.

The Reward

But let us not forget about the £10 reward; a useful sum to any man in 1828.

By informing Mr Heesom about the snatching of his daughter, Yeardley was eligible for the £10 reward.

But there’s a twist. Before informing authorities, Yeardley had made sure that Brown had delivered Hannah’s body to the surgeons and had received payment.

Although the fee was small, £2 7s 0d, the lions share would n doubt have been taken by Yeardley who by all accounts on this occasion appears to have been the teacher of a potential new recruit.

Why turn Brown in you say? Well, surely that would be obvious.

The small payment received for Hannah could be bumped up if Yeardley provided evidence as to the snatching.

It sounds as though no real guidance was given on Yeardley’s part for I believe Brown would have desecrated Hannah’s grave and spoiled the site for at least a year regardless if he’d received any help or not.

The consequences of forfeiting a graveyard for the sake of £10 is questionable. Either Yeardley didn’t see a further profit to be made at Whitkirk or he was hoping, that as time went by, the memory of the body snatchers ever having entered the churchyard would diminish and snatching could once again take place.

The real reason why remains unknown.

For his troubles Thomas Brown was imprisoned for one month with hard labour, William Yeardley walked away at least £10 richer.

Researching The Theft of Hannah Heesom

Hannah’s snatching appears frequently in the newspapers at the time and I have listed just a few of the sources below.

I access digitised copies of British newspapers via the British Newspaper Archive website although you do need a subscription to use the site in full.

I’ve included a couple of resources to get you started and you should easily find more from these.

Leeds Mercury – Saturday 24 January 1829

Leeds Intelligencer – Thursday 22 January 1829

![‘[A] Miraculous Circumstance’](https://mymacabreroadtrip.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Rawlinson-Resurrection-Men-via-Wellcome-Library-Diggingup1800-768x934.jpg)