Dissecting Season: When Body Snatchers Plied Their Trade

Someone once said to me ” a season for body snatching, who knew”, and I agree, not many do, which is why I decided to write a post dedicated to this ‘season’ and to discover why it was so important for body snatchers to be active in the colder winter months.

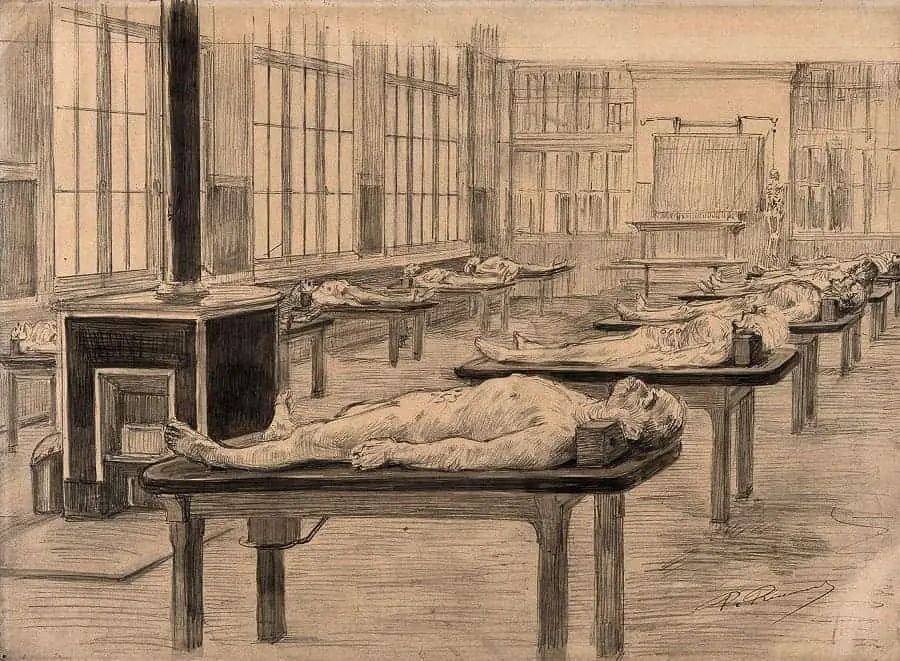

A cadaver, big or small, had one major flaw. Without modern preserving methods such as formaldehyde or refrigeration, it started to decompose, and decompose fast.

A large factor in helping to slow the decaying process was cold. And so it was only natural for students to study anatomy during the colder months from October to May.

Dissecting during the colder months helped a cadaver to stay fresher for longer. Body snatchers worked tirelessly during the dissecting period, supplying both teaching hospitals and private anatomy schools with corpses before the season ended when there would be no alternative means of getting an income.

I’ve delved into the unusual, yet practical, business methods of Britain’s body snatchers to discover just how they ensured they made enough money during this ‘dissecting window’ to survive the leaner summer months when there would be little or no body snatching opportunities available.

How Many Cadavers Were Needed?

During the dissecting season, cadavers would have been required in large numbers. Anatomists interviewed during the 1828 Report on the Select Committee on Anatomy stated that around three cadavers were needed per student in order for them to become proficient in their art.

If we consider student numbers for this period, we know that on average there were around 800 students in Edinburgh and London, not to mention those in Birmingham, Leeds, or Glasgow.

This makes for nearly 2,500 cadavers needed for the students of Britain’s two capital cities alone just so they could qualify.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that the six legally available cadavers from the gallows were woefully inadequate.

To get some idea of the number of cadavers supplied in one season we can turn once again to The Report on the Select Committee on Anatomy. Between 1809 and 1810, Joshua Naples, supposed author of ‘The Diary’ [see below] gave an account of the number of cadavers snatched by the Borough Gang within one year. For a summary we turn to James Blake Bailey :

the number of bodies disposed of in England was 305 adults and 44 small; but the same year 37 were sent to Edinburgh, and the gang had 18 in hand, which were never used at all.

Bailey picks up the tally for the following year:

312 adults were disposed of in the regular session [season], and 20 in the summer [season], in addition to 47 small

The demand for cadavers drastically dropped off when the warmer summer months arrived, however. Anatomy schools across the country generally closed their doors at the beginning of May with only a few extra-mural schools and private anatomy schools operating.

Opening Money

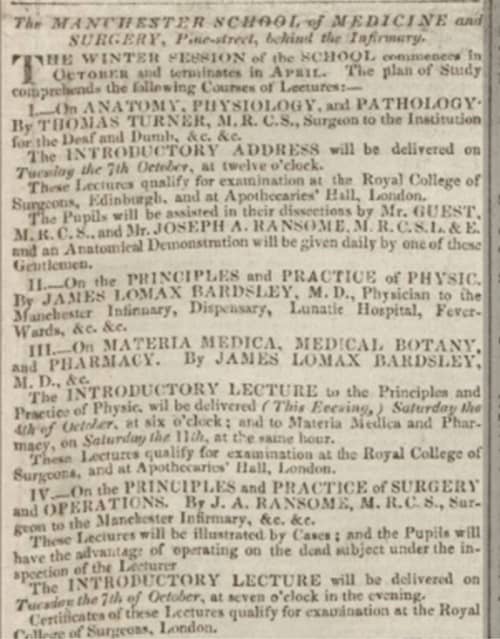

Lecture adverts for anatomy classes appeared in newspapers with many citing that they had the provision to provide a steady supply of fresh cadavers for their students to dissect.

This particular advert below, dating from 1828 and right at the start of the dissecting season in October, clearly shows that pupils would be operating on dead subjects.

There’s really only one place where these could have been obtained.

This was a tall order for surgeons to advertise the use of cadavers so openly. Especially when you consider that the only legally available source of a corpse was from the gallows.

To ensure that the anatomists could meet their promise and minimize the risk of students fleeing to neighbouring rival schools, a little bartering with the body snatchers was often in order to try to secure a decent price and supply.

To see the full effects of how opening money, and the rest of the business transaction played out, we need to really concentrate on London and the information we can glean from the anatomists ‘operating’ at the beginning of the 19th century.

Bartering

Anatomists were just as keen as the body snatchers to secure not only a cadaver but to get that cadaver at a fair price. It was common knowledge that the corpse was in high demand, and this naturally inflated prices as the era progressed.

Joshua Brookes, the proprietor of his own medical school which operated from his home in Great Marlborough Street, London, complained at the 1828 Report on the Select Committee on Anatomy that he had paid as much as sixteen guineas for a cadaver, a price that he certainly didn’t want repeating.

When you consider the price of a corpse at the turn of the century was often around £4, the price of sixteen guineas becomes rather eyewatering.

The Transaction

Resurrectionists would approach individual anatomy schools before the students returned, to discuss the terms of trade for that particular season. Don’t be fooled into thinking that the prices and favours that you may have benefitted from last year, would still be in place when a new season started.

Because of the tightly woven network created by this increasingly valuable commodity, those involved; sextons, coach drivers, and even watchmen, were all demanding a large slice of the profits. They knew there was money to be made from body snatching and they wanted their fair share too.

Anatomists were powerless against the demands of the body snatchers. Failure to agree would mean that the anatomy school wouldn’t be supplied with cadavers and your students would simply go elsewhere to study.

There wasn’t a simple solution of merely asking another body snatcher to supply them instead, for the London body snatchers had such a hold over who worked their patch, they would soon put any competing resurrection men out of business.

This monopoly can be seen in no better way than with the 1816 Great Cutting Scandle. After rival resurrectionists had supplied St Thomas’ Hospital with cadavers, the Borough Gang, London’s most notorious, and by all accounts main body snatching gang; headed at this time by a man named Patrick Murphy, was incensed.

Gang members broke into the dissecting rooms:

at St Thomas’s Hospital, assaulted two of the students, and [cut] to pieces two bodies prepared for the purposes of [the] lecture the following day… On Friday last, about six o’clock in the evening, four men again found their way into the dissecting room, and destroyed two bodies, a male and a female, before they were discovered…

Life would just be simpler for all of the surgeons who remained under the influences of the body snatchers.

Once a rate for the cadaver had been finalized, the resurrection men would also require money that they could use to bribe the watchmen of the churchyards and, as mentioned above, others involved in the supply chain.

This was of course usually pocketed by the gang leader and would rarely have been used for the purpose in which it was intended.

Delivery Money

Not all corpses carried the same value. The fresher the cadaver, the higher the price; as was proved by murderers Burke and Hare. But it didn’t take a murderous duo to drive up the price of a corpse, demand from anatomists and students doing this on their own.

In the beginning, let’s say, around 1810, a cadaver was fairly reasonably priced. Adults, male or female, would have cost around £4 4s as long as they were over 3ft in length, that is, just under one meter. Anything less than this then they would have been classed as a ‘small’, ‘large small’ or ‘foetus. If you fell into this category then you would be priced by the inch.

Higher prices would be paid for unusual corpses, perhaps the most well-known of these was the for the body of Charles Byrne also known as the Irish Giant. I mention Charles Byrne in an earlier post you can find here where I wrote on the different methods body snatchers actually used to obtain cadavers.

This links in quite well with this post as I describe the role of the body snatcher in quite some depth.

Finishing Money

When May evenings started to get longer and the warmer summer nights set in, students started to return home for the summer, anatomy schools closed their doors and body snatchers turned to their summer jobs; usually, something involving a ladder.

To ensure that your regular supplier of cadavers would return for the following season, anatomists dug deep into their pockets again and dished out finishing money to the body snatchers.

In 1827, Surgeon Sir Astley Cooper noted in his accounts that he paid £6 6s to three members of the Borough Gang, doing the same three years later in 1830.

Finishing money would at least give you some recognition when the season started again later in the year, although don’t be expecting too much favouritism, a body snatcher should never be trusted.

Researching the Dissecting Season

Reading about finishing/opening money and the way the anatomists tried to break the monopoly the body snatchers held over them is a truly interesting side of this strange period in history.

The 1828 Report on the Select Committee for Anatomy makes for fascinating reading and is available for free online via the Wellcome Trusts website here if you’re interested in reading further.

Newspapers

A quick search of the newspapers in the British Newspaper Archive throws up a number of lecture adverts for the schools offering anatomy and dissection.

The links provided next to the sources used will take you to the British Newspaper Archives website, as will this link here, but you will need to get a subscription in which to view the actual source. A free trial subscription is sometimes offered as is a pay per view option.

The Diary

We are extremely lucky in that a diary, thought to be written by Joseph Naples a member of the Borough Gang, has survived for the period November 1811 – December 1812. The Diary only consists of sixteen pages but provides a detailed account of the number of cadavers snatched, prices paid, and who the cadavers were sold to.

The original diary is kept at the Royal College of Surgeons, London, but due to its fragile nature is no longer issued. You can get a fragmentary copy written by James Blake Bailey from Abebooks.co.uk if you follow the link here

![‘[A] Miraculous Circumstance’](https://mymacabreroadtrip.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Rawlinson-Resurrection-Men-via-Wellcome-Library-Diggingup1800-768x934.jpg)