The Clink Prison Museum | London’s Notorious Prison + Medieval Torture Devices

This post may contain affiliate links. Please see my disclosure policy for details.

I’ve been to The Clink Prison Museum a couple of times before, both times I’ve barely had chance to get my camera out before I was hauled back onto the streets of London again.

But recently The Clink Prison Museum has been popping up again on my radar – but it’s one of those places that splits people straight down the middle.

Some reckon it’s fascinating, others dismiss it as a tourist trap.

Marmite in museum form.

So I went back. Not for the photo, or the tourist trap displays, but to see what’s left of one of England’s oldest prisons – and to see how The Clink Prison Museum tells its story.

If this sort of dark history interests you, then my newsletter might too. I share historical finds like this — plus historical true crime you won’t see in the history books. You can sign up here.

Table of Contents

What is The Clink Prison Museum?

The Clink Prison Museum is built on the site of Bankside’s most notorious prison – The Clink- and it’s thought that it gave us the phrase “in the clink.”

It began in 1144 when the Bishop of Winchester ordered the construction of Winchester Palace.

This new, purpose-built prison was actually two prisons within the palace grounds – one for males and one for females.

Before that, there’d been a simple prison cell here since around 860, when the land belonged to a priests’ college.

Over the centuries The Clink held debtors, drunks, sex workers (the infamous Winchester Geese), and later heretics. By the 16th century it was known for religious prisoners and eventually mainly became a debtors’ prison.

Its reputation for brutality stuck, helped along by links to the Babington and Gunpowder plots.

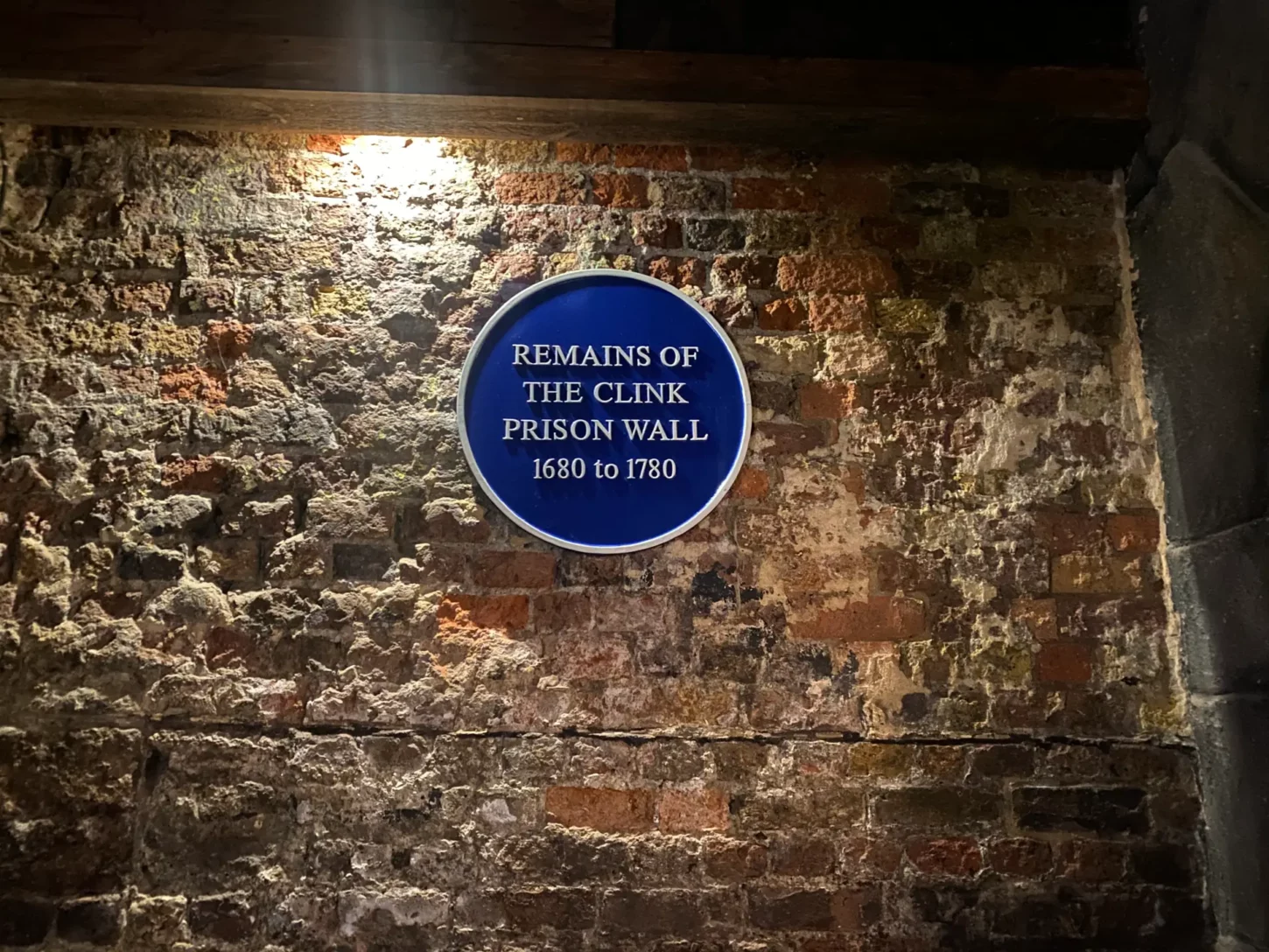

It ended in 1780 when the Gordon Riots set it on fire. The prisoners were released first – not officially – and the building was destroyed.

Today the prison is long gone, but inside the museum you can still see a section of the original wall.

Southwark and the Liberty of the Clink

The Clink sat in the Liberty of the Clink – Southwark’s free-for-all zone just outside the City’s control. Here the Bishop, not the King, set the rules.

Southwark was lively, unruly, and profitable: brothels, bear-baiting, theatres. Shakespeare’s Globe was nearby, as was the Rose Theatre run by Christopher Marlowe.

Today you can still see traces of the original Liberty: Clink Street, the shell of the Great Hall of Winchester Palace and its fabulous rose window.

How Old Is The Clink Prison?

The Clink was built in 1144 alongside Winchester Palace in an area of London known as The Liberty of The Clink. If it were still standing today, it would be over 800 years old. It was demolished in 1780 after the Gordon Riots destroyed the prison and was never rebuilt.

Life Inside ‘The Clink’

Conditions inside The Clink Prison were notoriously harsh.

Similar to conditions in the dungeons at Blackness Castle, the prison flooded regularly, leaving the prisoners waist deep in a mix of water and sewage, rats swimming past them in the filth.

Diseases like typhoid, dysentery and malaria were common; and many prisoners died before their trial.

The Rat Catcher

For those who couldn’t afford food, few matched the ingenuity of “The Rat Catcher.”

Henry Bronker, a long-term Clink inmate from 1670, clearly had a stomach of iron.

He’d fatten up the prison rats on scraps of parchment, leather, even human waste — don’t ask — then kill and eat them when they were ready.

Begging At The Grates

Corruption was standard practice in The Clink. If you had money, you could buy comfort: candles, fuel, bedding — even get your irons off if you greased the right palms.

The gaoler didn’t stop there. Brothel keepers were rumoured to keep business going inside, as long as the profits went his way.

For those without cash, life was harsher.

The best you could do was beg at the grates: pressing your face to the iron bars that opened onto the street, shoving your hands through to catch a few coins or scraps of food.

It was humiliating, and risky for passers-by.

As with Newgate, locals, I expect, learned to walk in the middle of the road rather than too close to the prison wall — pockets and purses were easy targets.

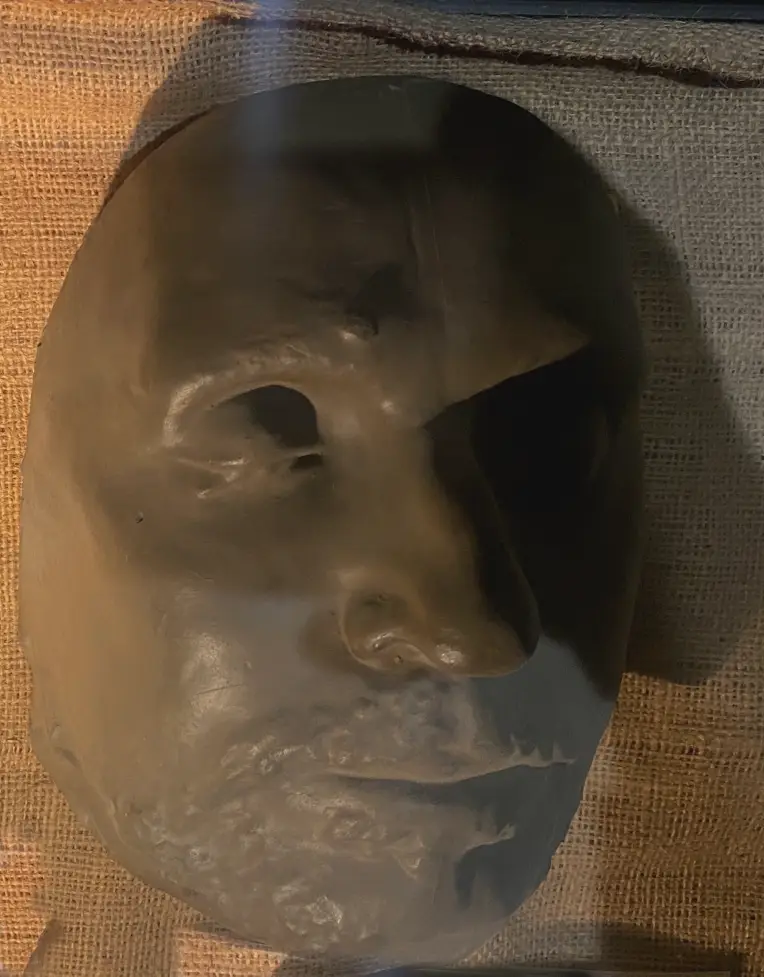

Torture Devices At The Clink Museum

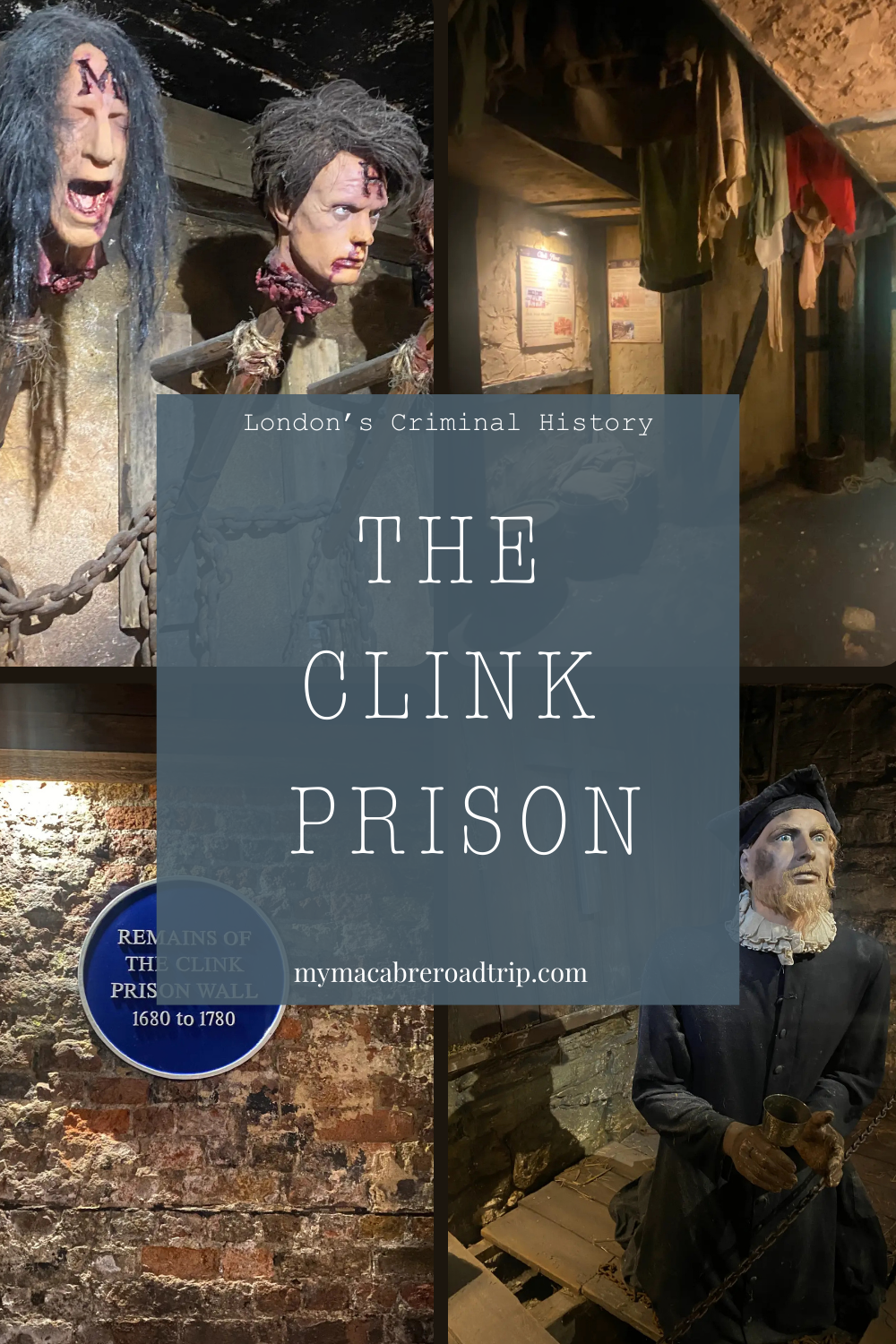

If you like ironwork, you’ll find plenty here. There’s a mix of replicas and originals , but the range is good.

From the smallest thumbscrews and tiny models of the infamous Scavenger’s Daughter, to the very solid looking torture chair, the museum certainly does not disappoint.

I’ve picked out the most notorious as it were – the things to look out for during your visit.

The Iron Boot

Waiting patiently on the floor in the museum’s torture room, this cruel punishment is one of the few medieval torture devices recognisable by its name.

The version at The Clink Museum is most likely a Spanish Boot – the kind that makes even modern readers wince, for it was designed to deliver a slow kind of torture.

Some boots were designed to hold liquid – oil or water – heated to boiling.

The one here worked differently.

The victim’s foot and lower leg were placed inside, small wooden wedges would be driven in around their ankle. Hammered down to ensure a snug fit, water was then poured into the gaps.

As the water was absorbed by the wood, the pieces would begin to swell, crushing the victim’s ankles and foot bones under the pressure.

The result was agony, often ending with the loss of the foot.

Scold’s Bridle (The Branks)

One of the most recognisable of all torture devices at The Clink is the Scold’s Bridle aka ‘The Branks’ – and the museum has three different variations on display.

The Scold’s Bridle worked more on humiliation rather than pain and was famously used on women who had too much to say for themselves – in other words, gossips or ‘scold’s’.

The iron frame of the bridle would be placed over the gossip’s head before she was led through town, much to her humiliation and the joy of her neighbours.

One example at The Clink Museum shows a small mouth plate that would have held down the wearer’s tongue so that they couldn’t answer back to the catcalling as they were receiving their punishment.

Other examples, such as the ones at The Tower of London, were designed to look like an ass’ head, and even had ears and a bell fitted to the frame.

Scavenger’s Daughter

Invented during the reign of Henry VIII, the Scavenger’s Daughter, also known as ‘The Spanish Cravats’ was a brutal device.

The museum shows the best-known A-frame design, which clamped around the neck, wrists and ankles, forcing the victim into a crouched position, often until blood gushed from the ears and nose.

But look closely inside a display case, displayed alongside a miniature rack, there’s an alternative design of Scavenger’s Daughter which reminds me of a griddle pan.

Here the victim kneels on an iron plate, an iron bar fitted over his (or her) frame.

The frame was screwed down tighter and tighter, crushing the victim into a ball until blood forced its way from ears and nose.

You can see a full scale replica of this style in the Lower Wakefield Tower at The Tower of London and it’s not till you see small models like the one on display at the Clink, that you realise how excruciating this latter design must have been.

Chastity Belt

Is this a torture device? Debatable? Its notoriety keeps it on the list.

Worn by women to “preserve virtue” while husbands were away; no such restraint was expected of men – they obviously had more willpower than us mere females.

Torture Chair

Arguably the museum’s main draw, the torture chair was an oversized seat – the museum’s is a replica of course – used to restrain victims, to hold them still while they were burned, cut or scratched.

A tamer variation to an iron torture chair or the Chinese torture chair which consisted of spikes or steel blades set into the in the arms and seat – oh and had the added ‘benefit’ of being placed near a fire to slowly roast the occupant alive in a way to persuade them to confess.

The torture chair at The Clink Museum looks to be made from wood and I’m not sure how this would have fared in a blaze.

Before we leave torture chairs, though, just take a moment to read this description of a torture chair from Cuenca, Spain.

‘ A vertical iron bar forms the back of the chair, to which is attached at the top an iron bridle fitted with a number of devices for compressing the head, piercing the ears, extracting the tongue, and crushing the nose. There is an iron restraining belt. Padlocks and manacles are attached to the lower section of the chair’

Horniman Museum

It’s kept at the Horniman Museum in the UK. Unfortunately, the picture on the website isn’t great but take a look if you want to see it for yourself.

It looks like a mash up of a scold’s bridle and a gibbet to me.

Whipping Frame

Another possibly inaccurate replica in the museum is the whipping frame – although you may be familiar with the more common, and simplier, whipping post.

Complete with luxury leather pads, it looks far more comfortable than the rough frames seen elsewhere. A similar whipping frame at Beaumaris Gaol, in the whipping room no less, is displayed minus the padding.

Traditionally, whipping posts (not to be confused with the pillory) were rudimentary affairs designed to inflict pain on the accused by, well, whipping.

They may have been incorporated into the village stocks or as simple as iron arm restraints attached to the trunk of a tree.

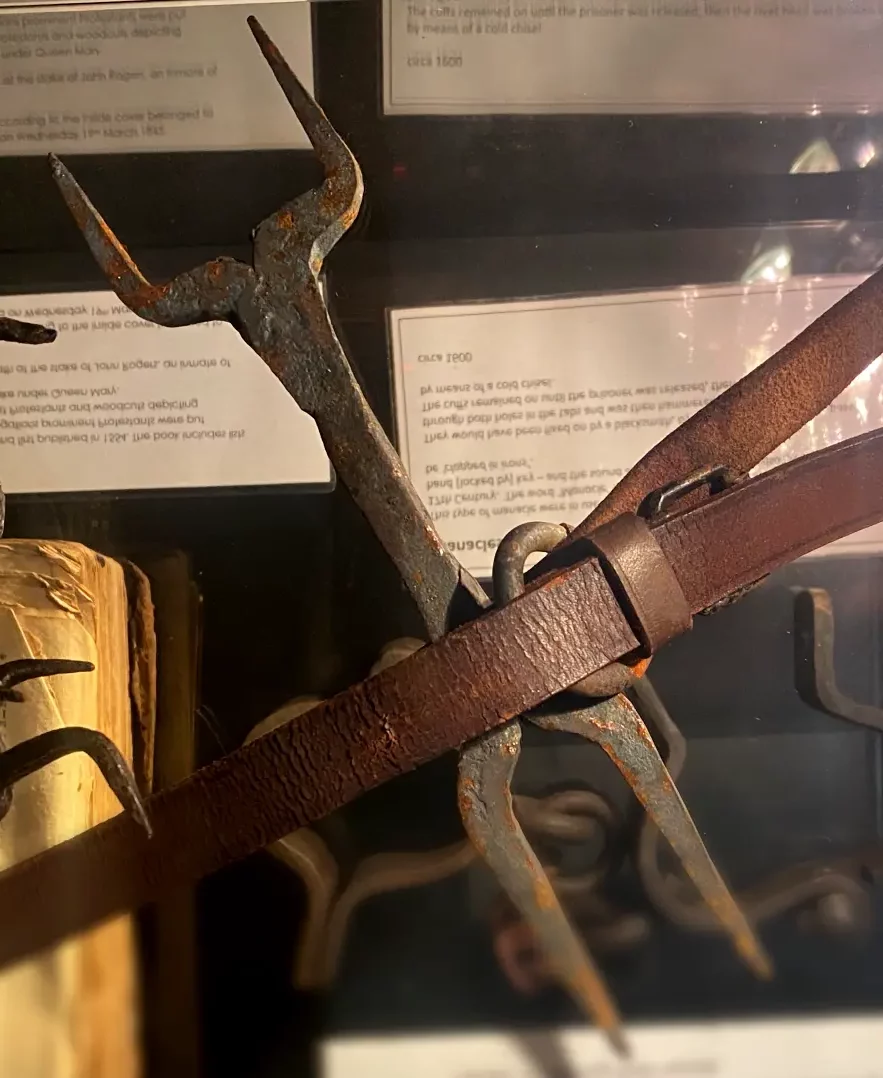

Heretic’s Fork

Fitting for a prison that once held heretics in the 16th century, the heretic’s fork was a simple yet painful device.

Two sharp prongs protrude from each end of an iron bar which was then wedged under the chin and against the upper chest.

Designed to extract a confession through sleep deprivation, each time the head lolled forward with lack of sleep, the deeper the forks sank into the flesh.

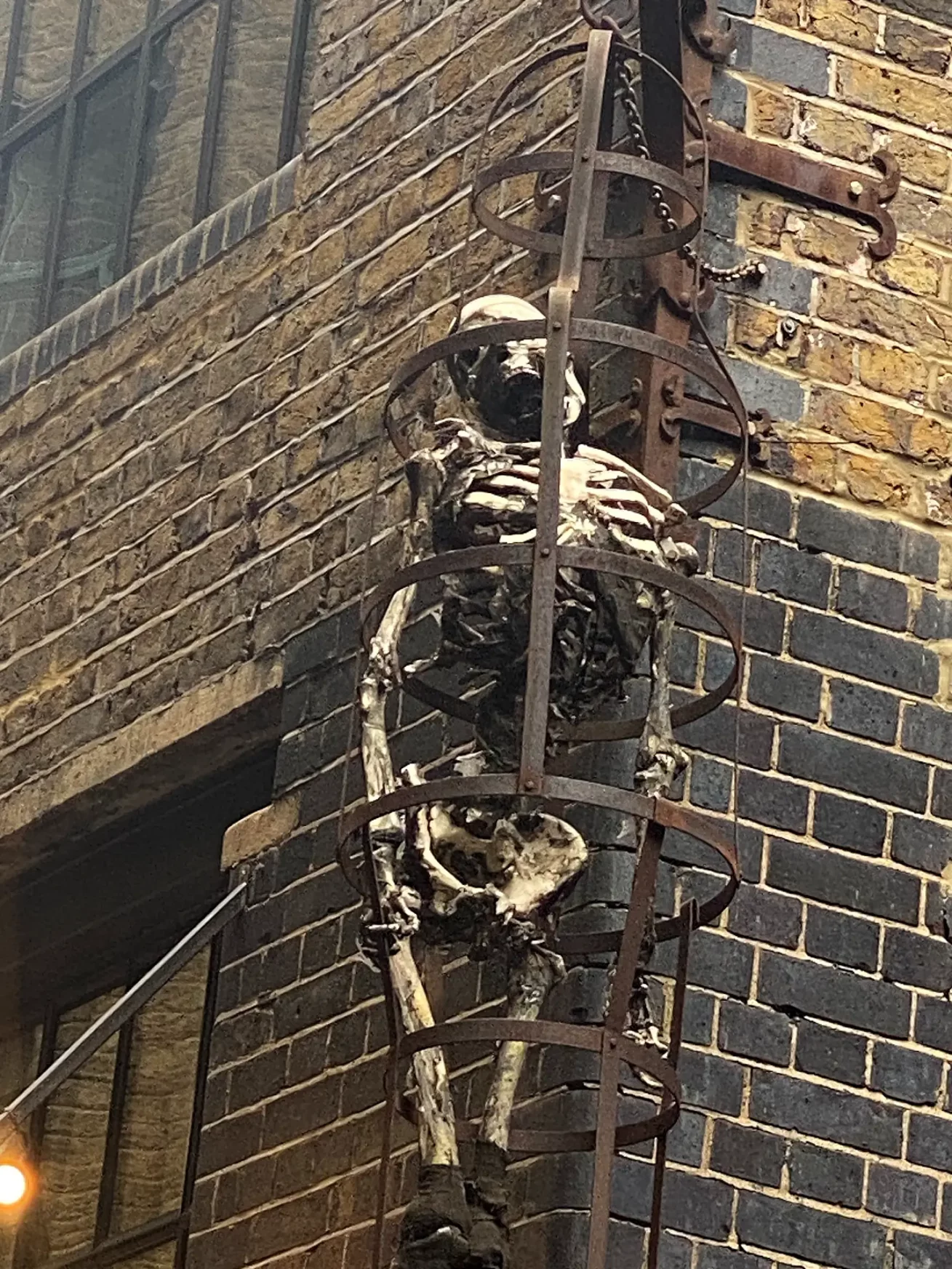

The Gibbet

If you ever needed a reminder to stay on the right side of the law, the gibbet was it.

More of a post-execution punishment, it was usually reserved for murderers, pirates, highwaymen and traitors.

After hanging, the body could be placed in an iron cage and displayed – sometimes for decades.

Bodies were often tarred to slow decay and hung at the roadside, at crossroads, or, for pirates, at low-water marks like Execution Dock in Wapping on the Thames.

The Clink has two examples, both cage-style – one outside, one in the torture chamber. I’d have liked to see a body-shaped frame for variety, but these make the point.

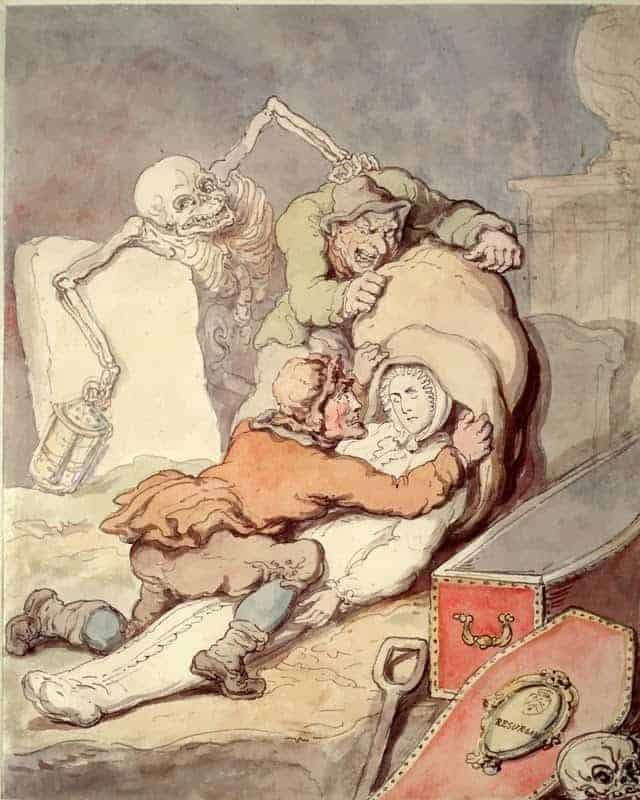

The Murder Act of 1752 had made gibbeting part of a murderer’s sentence – either be hung in chains or suffer dissection at the hands of the anatomists.

So feared was the thought of being dissected that hanging in chains was thought to be a preferential sentence.

The Murder Act 1752

…in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried’

By 1832, the last known use of the gibbet occurred in England until it was finally abolished in 1834.

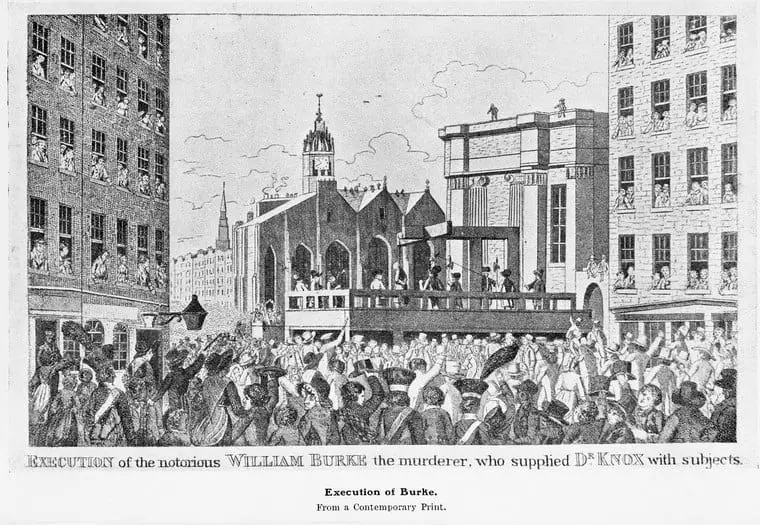

Scotland fell out of favour with the practice in 1810, and by the time William Burke was hanged for the murder of sixteen people in 1829, gibbeting was no longer considered harsh enough – and for Burke, public dissection felt more symbolically fitting for his crimes.

Famous Prisoners of The Clink

The Clink Prison saw its share of names, though few were what you’d call hardened criminals.

It took in religious dissenters, debtors, and anyone who crossed the rules of The Liberty of the Clink – which of course came under the whims of the Bishop of Winchester.

By the 16th century heretics were a focus, and the prison had ties to the Babington and Gunpowder plots.

- John Gerard, Jesuit priest, was held here in 1597 after a stint at the Poultry Compter and after being tortured in The Tower of London; he would later escape.

- Jasper Heywood, another Jesuit Priest, also spent time behind The Clink’s walls.

- John Rogers, who translated the Bible into English, may have been held here before his execution for heresy in 1555 (though Newgate was his final prison).

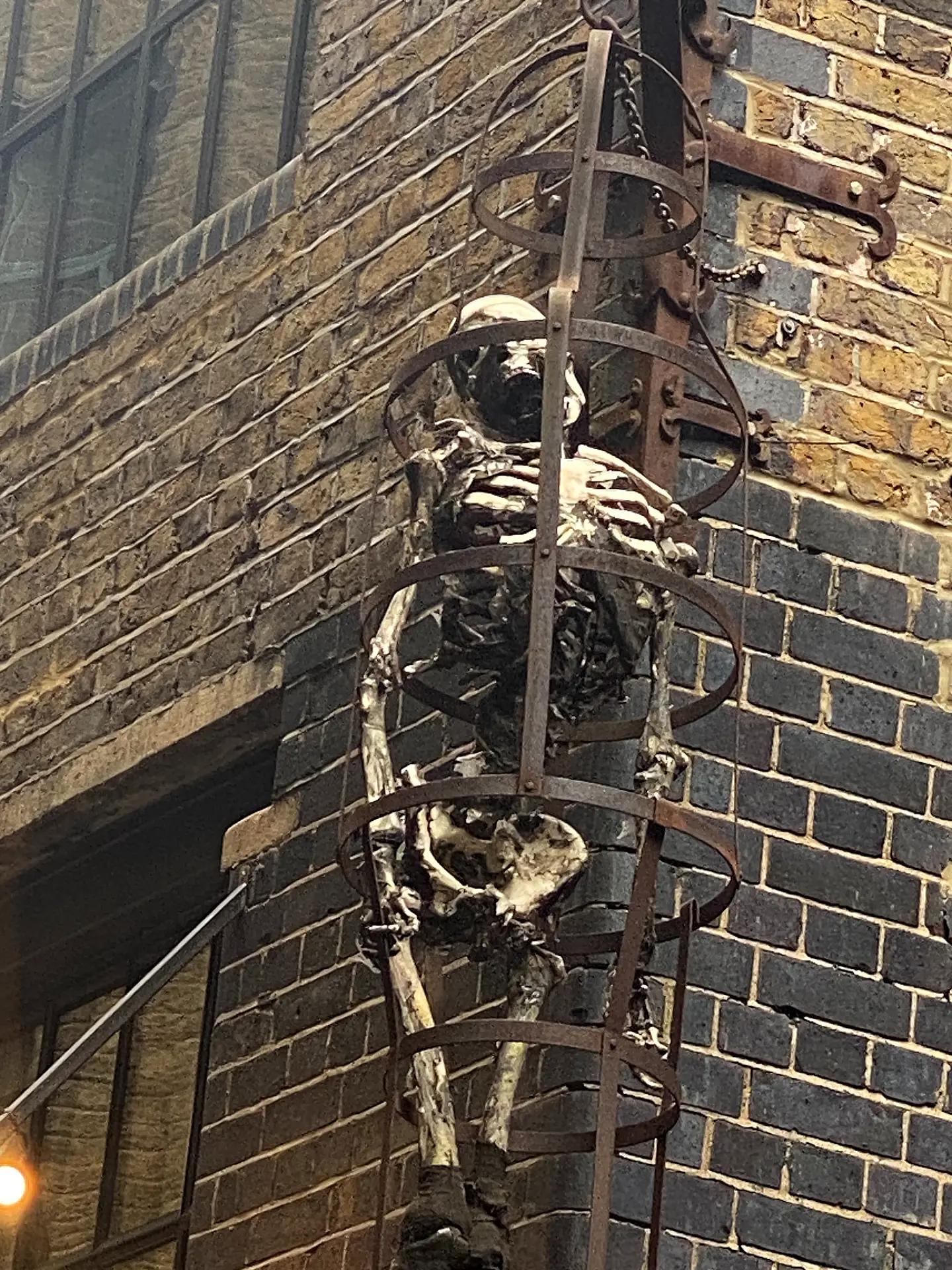

- The museum also shows a plaster cast of Oliver Cromwell’s death mask, one of five casts taken from the original wax impression in 1658.

Is The Clink Prison Musuem Haunted?

Perhaps.

Despite being labelled as one of London’s most haunted locations, I’ve only been able to gather a few stories to substantiate the claim.

The sound of rattling chains seems somewhat inevitable being in England’s oldest prison and a woman is said to have been heard rattling her chains during investigations.

A woman clad in a grey dress – the inevitable Grey Lady – has been heard weeping with a cold presence next to the cells.

Wandering priests and poltergeist activity has also been reported and the torture chamber – the place with the severed heads on poles – has been said to be particularly atmospheric.

Despite the lack of stories, I still very much doubt that you’d get me in here on a ghost hunting night!

Planning On Visiting The Clink? Add It To Pinterest

More Prison Stories

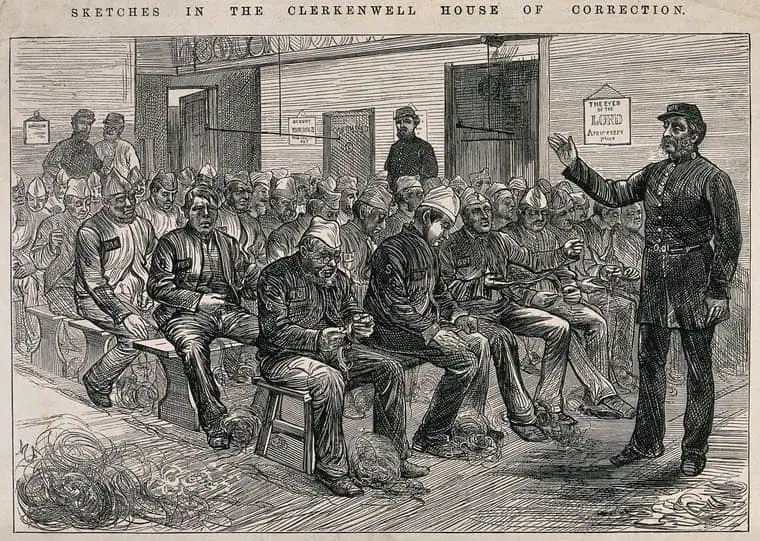

Picking Oakum In A Victorian Prison