Why Are There Cages Over Graves? It’s Not For Vampires!

This post may contain affiliate links. Please see my disclosure policy for details.

Spend enough time wandering around graveyards in Scotland, and chances are you’re going to come across more than a few cages over graves.

But what exactly are they and what are they doing there in the first place?

Well, stick with me as I tell you all about these strange cages, and take you on a very potted history of what is known as a mortsafe.

What you’re seeing are mortsafes and they were used to try to stop body snatchers from stealing dead bodies in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Bodies which would then be sold to the anatomy schools of England and Scotland.

Cages over graves, better known as mortsafes, first started appearing around 1816. As a general rule, they can usually be found in two different styles. One, a cage-like iron frame that fits around the coffin itself, and the other a heavier structure, again made of iron, that slides over the coffin, like an over-coffin or sheath. They were always designed to keep the dead in their graves, rather than to protect the world from zombies.

In this post, I want to share a deeper look at the history of the mortsafe, tell you why not all graves in a graveyard have cages over them, and give you some hints and tips about where to find some of the best examples still located in graveyards today.

Table of Contents

Why Do Only Some Graves Have Iron Cages?

This is perhaps the question that I get asked most often; if body snatchers were active in the graveyard, why then, aren’t all graves protected?

There’s a simple enough answer for this.

Mortsafes were often too expensive for individuals to purchase on their own and so a parish would often form a Mortsafe Society, clubbing together to buy a number of mortsafes, so everyone could benefit. On Average, a single parish might have two or three mortsafes on hand for when members of the society died.

Don’t get me wrong, some mortsafes were also bought by individuals, like these stunning examples from Cluny in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Or the trio of cages in the first picture on this post, the ones at Logierait, Perthshire.

This trio of mortsafes – that can’t get any nearer to a cage over a grave if they tried – would have been privately commissioned and it’s thought that they were designed for a family, two adults and a child. Equally, the four stunning mortsafes at Cluny, in the picture above were most likely to have been purchased privately.

Other more simple affairs would also have been purchased for personal use.

Simple Mortsafes

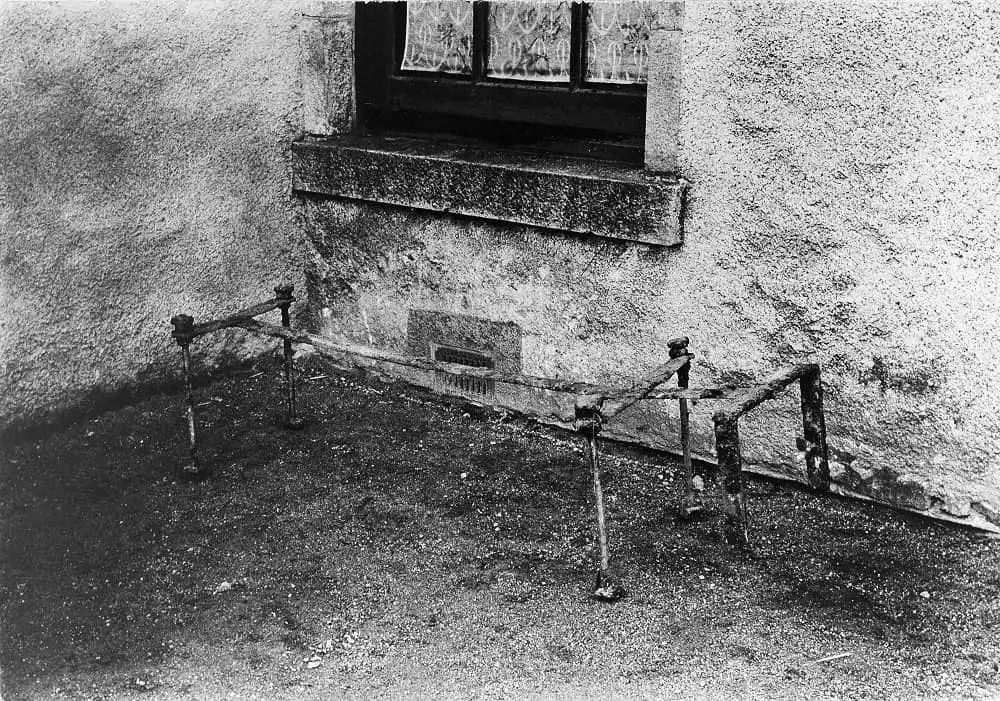

Simpler structures or mortsafes, purchased for private use, would have wrapped around the coffin and been permanently buried with it.

They often consisted of a series of iron bars that restricted access to the sides of the coffin, keeping the corpse, essentially, locked inside.

The example in the picture above, taken in 1911/12 is from a study by James Ritchie was found in the parish of Oyne in Aberdeenshire.

When I last went to see this, it was hidden under a HUGE mound of ivy, so much so that I had ended up getting in touch with the people who looked after the ground to see if it was still there!

It is, just in case you’re wondering!

Why Did People Put Cages Over Graves?

You’ve no doubt read the zombie theory about this one, that mortsafes were used to keep zombies in, or was it out? Or something along those lines.

I’ve read a few different variations and lost the will to live to try to look for a few specific examples (I hope you’ll forgive me) but unfortunately, this was not the case.

Mortsafes have only ever been used to protect the dead from the living. They were designed as a deterrent against body snatchers, otherwise known as resurrection men who targeted graveyards during the first half of the nineteenth century and stole fresh corpses from their graves, selling them to the local anatomy schools who dissected them in anatomy lectures.

The only case that I know of where a mortsafe has been used for something other than to project the dead – or as a Victorian addition to a burial plot – is when a cage, designed to look like a mortsafe, was placed over the cursed grave of Seath Mor located in the Old Parish Church Burial Ground in Rothiemurchus in the Scottish Highlands in 1983.

Legend has it that five stones or ‘homing stones’ protect his grave, cursing anyone who touches them.

Why Did Anatomists Need Cadavers?

As teaching methods towards anatomy started to change from the mid to late 18th century, medical students were finally given the opportunity to dissect a cadaver of their own rather than having to rely on a limb or torso that had been hacked ‘to death’ by fellow students in previous dissection lectures.

This new method of teaching known as the ‘Paris Manner’ was first introduced by William Hunter in his private anatomy school in Great Windmill Street, London in 1746.

Such was the demand and draw of his new style of teaching that students flocked to Hunter’s lectures and he regularly gave lectures with over 100 students in attendance.

But Hunter’s school on Great Windmill Street wasn’t the only private anatomy school to open in London that was demanding bodies for dissection.

The Legal Supply Of Cadavers

In her fabulously researched book ‘Death, Dissection and the Destitute’ (which incidentally, should be on every medical historian’s bookcase) Dr Ruth Richardson, notes that by 1826, that’s three years before Burke and Hare were caught murdering victims in their lodging house in Edinburgh, there were eight independent anatomy schools in London alone.

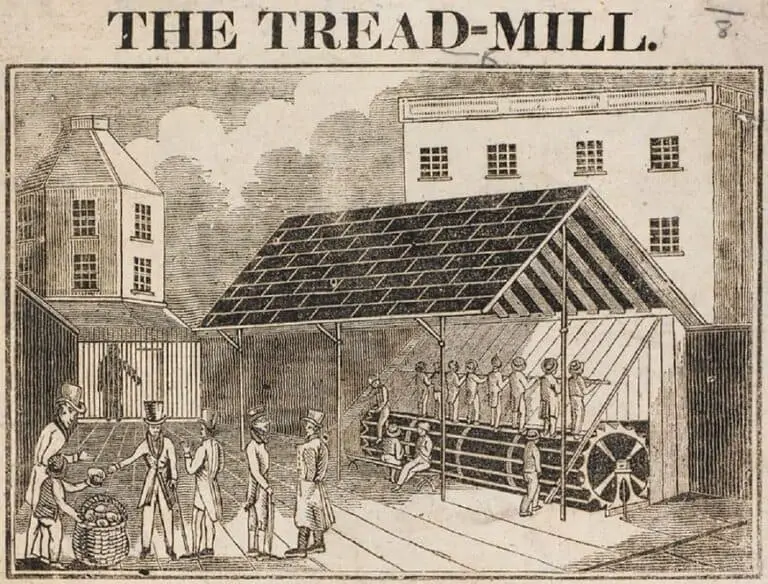

With the legal supply of cadavers being a mere six corpses obtained from the gallows on hanging day, and with a student population thought to be nearing 1000 in just Edinburgh and London alone, it doesn’t take a genius to realise that the supply fell drastically short of these new expectations.

Anatomy Students

In fact, the supply of cadavers wouldn’t meet demand for well over 100 years and so to ensure the success and growth of the private anatomy schools and to quench the insatiable thirst for knowledge of Britain’s anatomists, there was only one thing for it, dig up your own bodies for dissection.

In the beginning, this need, while still relatively low, was satisfied by the students and anatomists themselves.

Glasgow students for instance are said to have been able to pay their tuition fee in cadavers – not a bad gig if you can get it.

As the demand for fresh cadavers increased and with the law changing in 1788 making the act of body snatching a misdemeanor, opportunities gradually opened up for a professional set of men to take over.

But I’m in danger of going down another rabbit hole here, so if you want to know more about the life of a medical student and their body snatching antics, head on over to my post here on the subject. I think you may enjoy it.

That said, if you want to know what eventually drove the anatomists and students out of the graveyard and back into the dissecting rooms, then take a look at my larger post where I look at early bodysnatching and the rise of the professional bodysnatcher

How Did People Get To Use A Mortsafe?

You’ll remember I mentioned that mortsafes were just too expensive for most parishioners to even consider buying. So what did people do when they feared their loved ones would be targeted by the resurrection men?

As a general rule, if people wanted to protect their dead using a mortsafe they would have belonged to a Mortsafe Society. Many parishes, although not all, had a payment scheme, a Mortsafe Society, to which you paid a few pence each week. For this, you would be given permission to use the mortsafe for a required number of weeks, usually six, after you die.

I know what you’re wondering, why six weeks?

Well, after this period your body would have been too putrid to have been of any benefit to the surgeons and so the body snatcher would have moved on to someone else’s grave, leaving yours alone.

That said, there was still the odd occasion where calculations got a bit messed up and a ‘not so fresh’ cadaver was lifted from its grave.

When I was researching for my book, ‘Britain’s Forgotten Bodysnatchers’, I came across two rookie resurrection men, William Whayley and William Patrick, who dug up a none-too-fresh specimen on their first body snatching raid in Peterborough in 1830.

They weren’t put off by this disastrous event, however, for a fortnight later they were at it again, this time with much more success!

Body Snatcher Joseph Naples

Another body snatcher who didn’t let a few decomposing body parts get the better of him was the London snatcher, Joseph Naples.

He was known for cutting off extremities and his ‘speciality’ apparently, was heads!

If you’re a regular to my blog, you’ll know that Naples is a favourite amongst my posts and you can read a cracking story about him here about the time he broke out of Coldbath Fields prison in 1802.

I love it, mainly because the man had enough front to mail back his prison uniform after he’d escaped, saying he no longer had any need for it! Just fabulous!

Or, if you prefer, you can catch up on his time as a member of the notorious Borough Gang in my post A Week In The Life Of A London Body Snatcher I think there may be mention of a few extremities in this post too.

Mortsafe Societies

As mortsafes were predominantly a Scottish deterrent, it’s hardly surprising then that most, if not all Mortsafe Societies can be found in Scotland.

Most societies operated on a similar system, having parishioners pay an entry fee, followed by an annual subscription fee.

Anstruther Mortsafe Society

Take for example Anstruther Mortsafe Society who charged an entry fee of 3d to each parishioner and then an annual subscription fee of 6d.

The parish started off initially with five mortsafes but then increased this number by a further two a few years later. Their largest mortsafe was said to have been a whopping 7ft long – long enough to accommodate even the largest inhabitant and their coffin.

Lying between Aberdeen and Edinburgh – two cities with an equally high demand for cadavers – you can see why Anstruther invested so heavily in protecting its dead.

Linlithgow Mortsafe Society

Linlithgow, in Midlothian, established a Mortsafe Society in 1819 which was known properly as ‘Linlithgow Mortsafe Association For Protecting The Dead’.

Entry to the Association was 5s, slightly higher than Anstruther’s but all members of the family could use the mortsafe.

But the parish still didn’t feel protected against the plight of the body snatcher for only four years later, a ‘Watcher’s Hut’, built to keep three watchmen warm and dry during the watching hours, was erected in the churchyard on the south wall.

Unfortunately, however, only the broken mortsafe has survived the ravages of time and, on my last visit, it lay damaged and rusting on the floor near the church wall.

What Happened To Mortsafes When Body Snatching Ended?

In 1832, the Anatomy Act was passed, promising to put an end to body snatching once and for all, thus making all this ironwork in Scotland’s kirkyards redundant. (It didn’t by the way, but that’s a huge story all of its own).

But was it just a case of whoever got to use the mortsafe last, simply had it leftover in their grave in perpetuity?

Not really. There are a few mortsafes still in situ where it’s pretty obvious that it was its final resting place as it were.

Lennel in the Scottish Borders has a very rusty example of a mortsafe buried in the ground on the north side of the now ruined church – that is the side nearest to the road if, like me, you don’t carry a compass around with you.

I visit this site regularly when making my way up to Scotland and with each visit the mortsafe has deteriorated just that little bit more.

I hope that it is preserved at some point and not left to decay like so many of these relics are.

Another firm favourite of mine is the mortsafe at Kilmaurs in Ayrshire.

This one is on another level and is the one in the image above. All that’s visible are the three iron hooks sticking out of the ground.

I love it and often wonder how many lawnmowers it’s damaged over the years!

The End Of Mortsafes

A large proportion of the mortsafes that were made are now lost to us.

Take the Anstruther mortsafes mentioned above, for example, they were sold in 1874 for scrap metal for the grand sum of £6 (around £375, and the same price as a cow at the time!).

A similar fate occurred to the Inverurie mortsafes and those in Kemnay in Aberdeenshire, broken up and sold as scrap metal more than likely, once the fear of body snatching had subsided.

The proceeds of some sales went to good use, however. Cumbernauld in North Lanarkshire sold its mortsafe in 1851, the proceeds being put back into the local Eye Infirmary and Royal Infirmary, guaranteeing three beds in perpetuity for parishioners.

Others, as we know, have survived and have become a minor draw for tourists wanting to search out the macabre.

I am, of course, referring to the now world-famous examples of the ‘double bedder’ mortsafes in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh.

But what about those that have perhaps slipped under the radar a little?

Many were destined to become scrap metal, especially with the scrap metal drives in WWII, but others did survive and were found stuffed through hedges and used as cow troughs and have now been relocated back into churchyards such as the one in Kirkton of Durris, Aberdeenshire in the picture above.

Best Places To See A Mortsafe

At the beginning of this post, I promised I’d tell you where to find the best mortsafes and there are some real treasures out there let me tell you.

I recently shared my top seven alternative body snatching sites outside of Edinburgh in another post here which I really enjoyed writing and which made me want to discover these places for the first time again.

There’s everything from mortsafes to watch houses in this post so I hope you’ll enjoy it too.

My absolute favourite has to be the four mortsafes at Cluny in Aberdeenshire, three of which are shown in the picture above.

I’ve never seen anything like these before and to say I’ve been researching body snatching for nearly 20 years now, apart from visiting my first site at Oxnam in the Scottish Borders all those years ago, the mortsafes here are just out of this world.

If you want to go exploring for yourself, then one great guide for keeping in your glovebox and one which I recommend time and time again is Geoff Holder’s Scottish Bodysnatchers: A Gazetteer.

I’ve had my copy for over 7 years now and am in desperate need of a new one, it’s got so many notes over it, that it’s not funny anymore. I use it as the basis when planning most of my road trips.