What Did Body Snatchers Do?

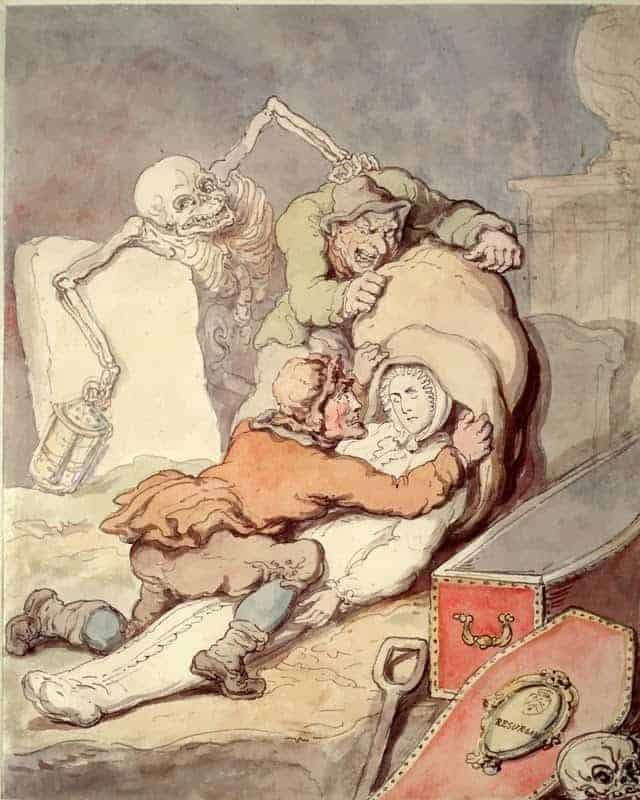

When we mention the words body snatching, most of us know that it involved men, and occasionally women, digging up dead bodies and selling them to anatomy schools for use in anatomy lectures.

But how and when did a body snatcher know that a cadaver for available for the taking?

A number of methods were used to help locate a suitable cadaver for the surgeons. Requests for specific cadavers were made but in general, body snatchers would have carried out reconnaissance trips, pretend to be relatives of those who died in the workhouse, and, as time went by, steal cadavers from houses.

Opening a grave and stealing the body within it was perhaps the most common form of acquiring a cadaver for the surgeons. But not all bodies arrived on the dissecting table from this route.

In this post, I want to cover some of the main procurement methods used by body snatchers during the 19th century.

Not everything is covered, but as a general rule, we can say that most body snatchers worked using the methods mentioned below.

Requesting Specific Cadavers

It was not unheard of for surgeons to set their hearts on a specific cadaver once it had been buried.

An anatomist’s hunger for discovery didn’t stop on the dissection table and surgeons often made specimens of unusual finds to keep in private collections or for use when teaching future students.

These specimens, wet or dry, were either obtained through discovery during dissection or via specific requests.

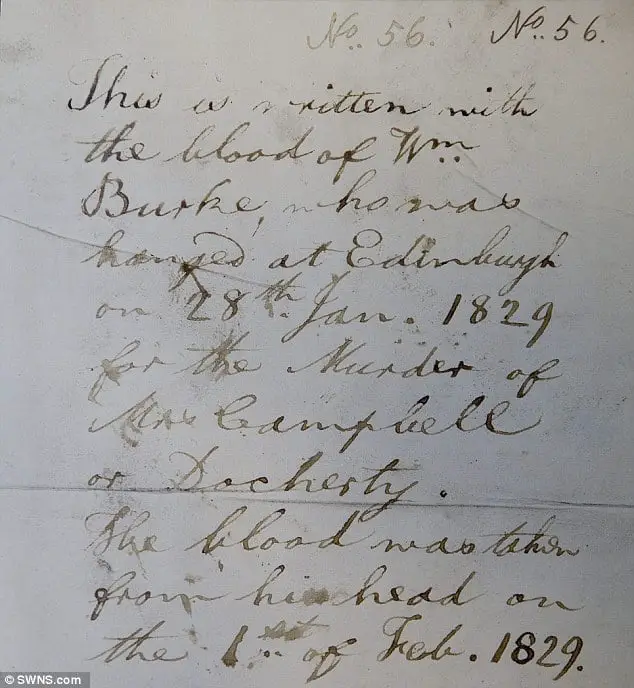

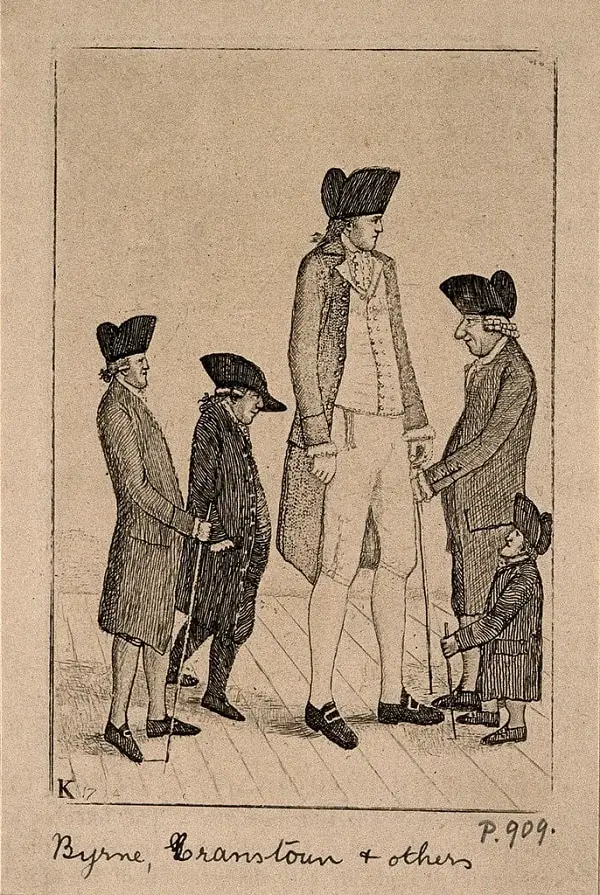

The ‘Irish Giant’: Charles Byrne

Perhaps the most famous of these requests was for the body of Charles Byrne, better known by his nickname ‘The Irish Giant’. In an era where the average man’s height was around 5ft 5in, Byrne was alleged to measure anything from 8ft 2in to 8ft 4in.

His skeleton, which, at present [1] is still in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons, London, however, tells the real story for Byrne actually measures a mere 7ft 7in.

Such an unusual cadaver would have been highly sought after and Byrne, who died in 1783, was eventually bought by the anatomist William Hunter for £500, the equivalent to over £30,000 today and added to his private collection.

Other requests came from surgeons who were curious as to the success of an operation.

In the 1820s, Sir Astley Cooper, eminent surgeon to King George IV tasked two of his regular body snatchers Vaughan and Hollis to travel from London to Norfolk to collect the body of a former patient.

His reason was purely for the fact that he’d carried out an operation (a ligatured aneurysm) on the man some twenty years previous and wanted to see the results. The sum of seven guineas was paid for the corpse alone.

Reconnaissance Trips

Although requests for specific cadavers did happen and were, in reality, quite common, one of the main ways a body snatcher knew that a cadaver was available was by attending a funeral themselves and going on reconnaissance trips.

Women, often spouses, would act as mourners at a funeral as they attracted less attention. They would stand looking forlorn at the churchyard wall in the hope that the sexton would come over to see that everything was ok.

This first encounter was engineered to secure an invite to the funeral, thus giving a prime opportunity to look in the grave and assess its depth, and most importantly, to engage in conversation with the sexton to find out how the deceased met their end.

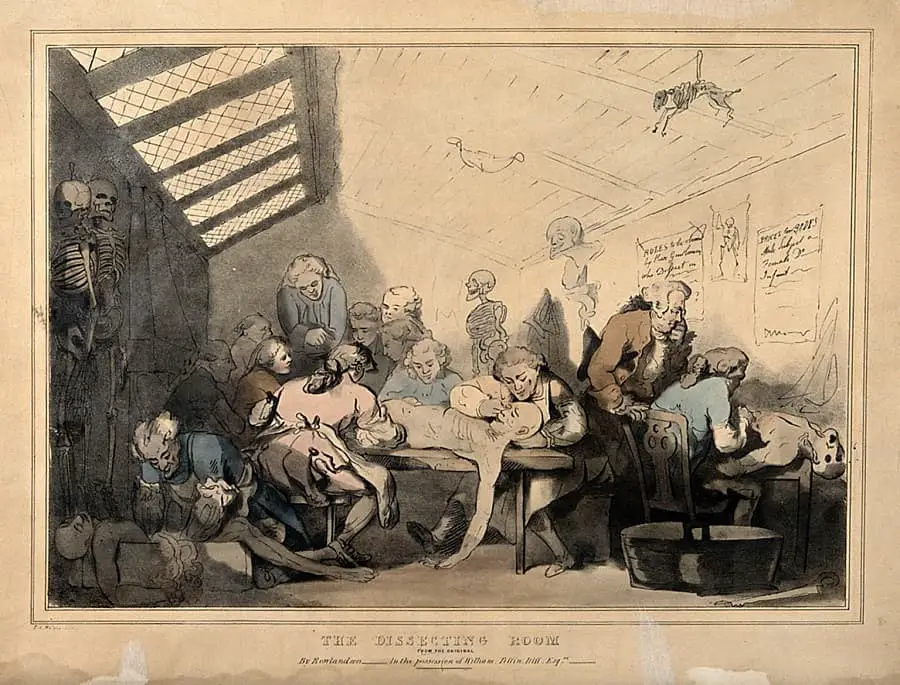

Determining the condition of a cadaver before snatching it was crucial. Cadavers that died a natural death were favoured against those that had died through accidental means.

In a natural death, anatomists could see the full muscle groups and put theory into practice. If a body had been mangled from an accident, then internal structures could be damaged and be of limited use.

That said, if a slightly decomposed cadaver was dug up in error, as was the case in Peterborough in 1830 when William Whayley and William Patrick misunderstood instructions, the extremities could always be taken off [2][3]

A member of the Borough Gang working in London, Joseph Naples specialized in cutting off extremities and is recorded selling extremities to Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1812, receiving one pound for them.

Body snatchers themselves also scouted out fresh graves in which to target.

Leeds body snatcher John Craig Hodgson, arrested in 1831, gave his gang members a list of the graveyards he wished to visit, whereas body snatcher William Hodges had been seen for several weeks about the burial ground at Poplar Chapel in London after service on Sundays.

During a scout, it would be noted if there were any measures placed on the grave to try to deter the body snatches. These could range from piles of sticks or stones that the poorer members of the parish would use, to noting the placement of wires from a cemetery gun.

Nothing would have been left unrecorded so that their presence in the graveyard would remain unnoticed.

The Unclaimed Dead

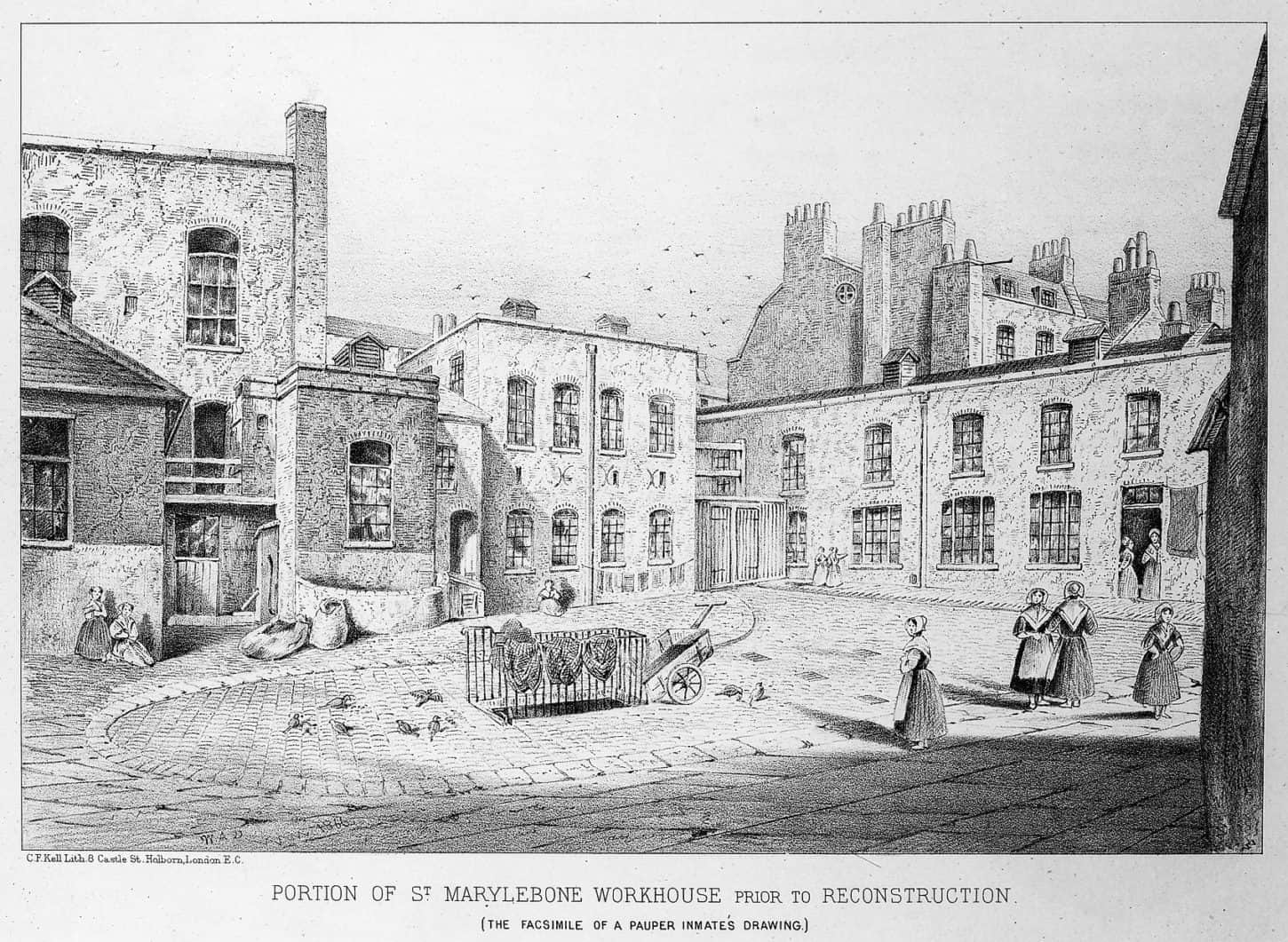

A parish was only too happy for someone, anyone, to claim ownership of an individual who died a lonely death in the workhouse.

Women again were employed by body snatchers and were experts at pretending to be a long lost relative of the deceased, having had ‘no idea’ that they had even ended up in the workhouse.

If, however, no one had come forward for the body, it would then be subject to a pauper’s burial. A burial that everyone feared and one which drove up the popularity of Burial Clubs.

A pauper’s burial meant an undignified burial in a common grave; buried in a cheap coffin without a gravestone. Pauper graves were an easy target for body snatchers.

Not only were there multiple bodies to target in one ‘hit’ as it were but the bodies would have been buried relatively shallow, both factors leading to an easy target for the resurrection men.

Stealing From Houses

As the era moved on and body snatchers got a little bolder, greater risks were taken in procuring cadavers.

Bodies would be stolen from coffins as they were lying at home waiting to be buried and we know of at least one body snatcher, William Jones, who was apprehended in 1831 as he exited a house with a cadaver in a basket.

Many body snatchers had alternative employment as burglars during the summer months when cadavers weren’t required in such great quantities by the anatomists, so breaking into a house for a corpse was seemed to be an obvious next step for many.

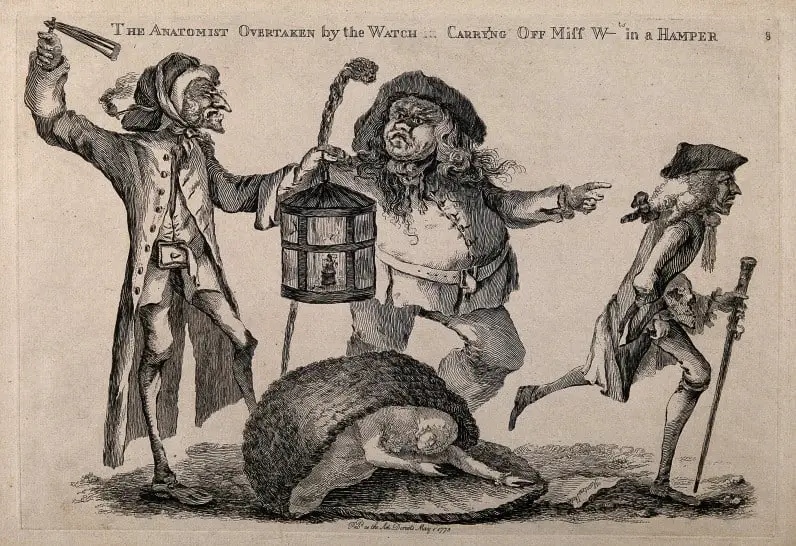

As Members Of The Watch

One way of safeguarding your loved ones from the body snatchers was to employ a watch.

A watching committee would be raised through subscription, with local members of the parish acting as the watchmen.

But members of the watch could either be paid off, or in some instances, dealt with in an entirely different manner.

We know of two body snatchers who took things to the extreme after they were employed to watch over the graveyard in 1817.

Thomas/William Duffin and William/John Marshall were employed to watch over the graves at St Mary’s Church in Lambeth, but the repeated snatchings made their employers suspicious and a watch was set up to watch the watchmen.

It was discovered that they were regularly removing corpses from their graves and selling them to the local surgeons.

A Side-Line In Teeth

It was an unwritten rule that before delivering a cadaver to the surgeons, body snatchers would remove the teeth.

The reason for this was twofold. If you had to abandon your cadaver half way through a snatching, you’d still have the teeth, as these could be kept in your pocket. There was also a healthy profit to be made from selling the teeth separately.

Whacked out with the handle of a bradawl or twisted out with a pair of pincers, the teeth would then be sold separately to dentists for artificial dentures.

Members of the Borough Gang made their way to the battlefields of the Peninsular War to steal teeth, returning home to sell them for £300 profit after just one trip.

Gravedigger turned body snatcher, James Foxley, targeted the grave of nineteen-year-old Jonathan Bedford in order to get at his teeth and in 1830 when Thomas Goslin, alias Vaughan, a former member of the Borough Gang was apprehended in a parish in Devon, the teeth from around fifteen cadavers were found at his lodgings.

But why this craze for human teeth?

The upper class in Georgian Britain wished to rectify their depleting smiles by wearing false teeth. Artificial teeth made of ivory or porcelain tended to discolour quickly, and so human teeth were sought after, providing a more natural appearance.

Not all procurement methods have been covered here, but we can safely presume that the methods that have been included were in regular use by the body snatchers.

If the opportunity arose to take a cadaver, then the body snatcher would have acted upon it. The punishment was such that if they stole the corpse and nothing else, a few weeks of imprisonment was worth the risk of getting caught.

Taking It Further

[1] There is talk of the Hunterian Museum respecting Charles Bryne’s final wishes and burying him at sea following a refurbishment of the museum, set to reopen in 2021. You can read about the proposal via their website here

[2] You can read more about the cases mentioned in this post, plus others, in my book Bodysnatchers: Digging Up The Untold Stories of Britain’s Resurrection Men’ available to buy via abebooks.co.uk or Amazon.co.uk and all good retailers.

[3] For a full comprehensive study of body snatching, Ruth Richardson’s ‘Death, Dissection and the Destitute’ is an excellent publication. You can buy it via Abebooks.co.uk or Amazon.co.uk