Famous Body Snatchers of London

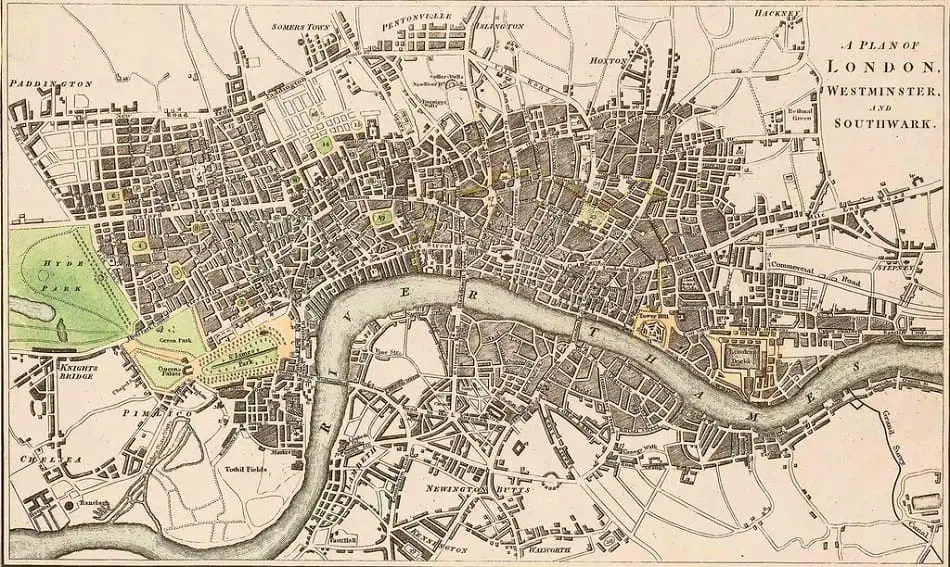

London before the 1832 Anatomy Act was a grim and desolate place. The macabre practice of body snatching thrived in its underworld and the characters involved in the art were often of the lowest type.

But who were these men who scurried about the city streets at night and in broad daylight? Someone is only famous if you know them, and in the world of body snatching, the men I’m about to introduce to you are perhaps the most notorious of them all.

London’s most famous body snatchers come from two distinct periods in the 19th century. In the 1810s the Borough Gang dominated the scene. As the gang disbanded and went their separate ways, they were replaced by the ‘London Burkers’ Bishop, Williams and May in 1831. These names dominate the world of body snatching history in London, with just a few individuals on the periphery occasionally making their appearance.

We know of their crimes, but who were the individuals behind these soiled knees and pungent smells of a cadaver? Who were the men that stole corpses in the dead of night and how did they get into the world of body snatching?

From leaders in their field the Borough Gang to the man who is still remembered in history as ‘The King of the Resurrectionists’, it’s time to take a look at the men behind the names.

The Borough Gang

Mention London and body snatching too many historians and you often get the same responses. The Borough Gang, so-called because of their location in Southwark which had been known as ‘The Borough’ since the 16th century, and the ‘London Burkers’, Bishop, Williams and May.

We’ll meet the London Burkers later on but for now, I want to concentrate on the first professional gang to work in London, the Borough Gang.

At the turn of the 19th century, this gang, at that time headed by Ben Crouch, dominated supplies in the City.

With a carefully crafted system and a network of informants ranging from gravediggers to policemen, the Borough Gang were very protective over their ‘patch’. Such was their influence over anatomists that the notion of obtaining supplies from a cheaper source would mean a complete freeze on all cadavers. Competition was dealt with swiftly.

When a rival did try to muscle in on the scene they thought nothing of putting them back in their place. Revenge was sweet and came in a number of guises. Either the authorities would be informed of their antics or more dramatically, the gang would ‘spoil’ the graveyard.

Putrid cadavers would be thrown over the grass, burial shrowds scattered around gravestones and even, on occasion, empty coffins hoisted onto the churchyard wall for a disbelieving public to see.

Such antics would immediately spark an investigation, leading to a domino effect. Men, supposedly in authority, would be ousted if they were discovered to be colluding with body snatchers or anatomists. Sextons, tempted away from their honest job by the money to be made from selling cadavers forfeited their position for the sake of greed.

It didn’t pay to get on the wrong side of the Borough Gang.

Ben Crouch: Leader of The Borough Gang

Ben Crouch was, by all accounts, a snazzy dressing boxer with a pox marked face and a love of gold jewellery.

He led his band of men through the first decade of the 19th century, when the demand for cadavers was reaching its first peak and when competition and detection were low.

Crouch was the son of the carpenter at Guy’s Hospital and was introduced to body snatching by Sir Astley Paston Cooper, who by 1813, right in the middle of this first wave of body snatching, was appointed professor of comparative anatomy to the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

He had a character that became abusive when mixed with alcohol and Crouch tended to remain sober for the most part, especially when dividing up takings. It was easier to swindle your comrades if they were drunk and you were not.

By 1817, Crouch’s involvement in body snatching grew less and after a volatile period of working with horses, he would accept an offer to head to Edinburgh to continue his body snatching ways.

He would eventually invest his money in a hotel in Margate but unfortunately, locals discovered his background and learnt where the capital had come from with which to purchase the hotel and the venture failed.

Returning to the lucrative trade in human teeth, Crouch became desperate and embezzled money from his former gang member Jack Harnett. He was imprisoned, after being pursued by Harnett and upon his release was never the same again.

Accounts say that he lived in poverty, dying suddenly where he sat; upright in a tap room near Tower Hill.

Joseph Naples: Author of a ‘Diary of a Resurrectionist’

Joshua or Joseph Naples, for his name appears as both, was once a respectable member of the community.

Having served in the navy on board HMS Excellent and fighting under Nelson and Admiral Sir John Jervis at the Battle of St Vincent in 1797, Naples became a gravedigger at St James’s church in Clerkenwell in 1800.

He soon discovered the slippery slope of corruption however and only two years later is known to be providing students from St Bartholomew’s Hospital with cadavers after arrangements were made to leave empty hampers out for him to later fill with bodies.

His role as gravedigger put him in easy access to fresh supplies something that he appears to have taken full advantage of. His demise came when he was imprisoned for two years in the House of Correction after a corpse being discovered during delivery was traced back to St James’s churchyard.

On his release, he had little option but to join the Borough gang, all ideas of working in an independent capacity blocked by Crouch himself.

Naples’s specialism was in extremities. He favoured removing the head, arms and legs of cadavers that would then have been sold separately for demonstration purposes. He also traded in teeth, as all good resurrection men knew how.

‘Diary of A Resurrectionist’

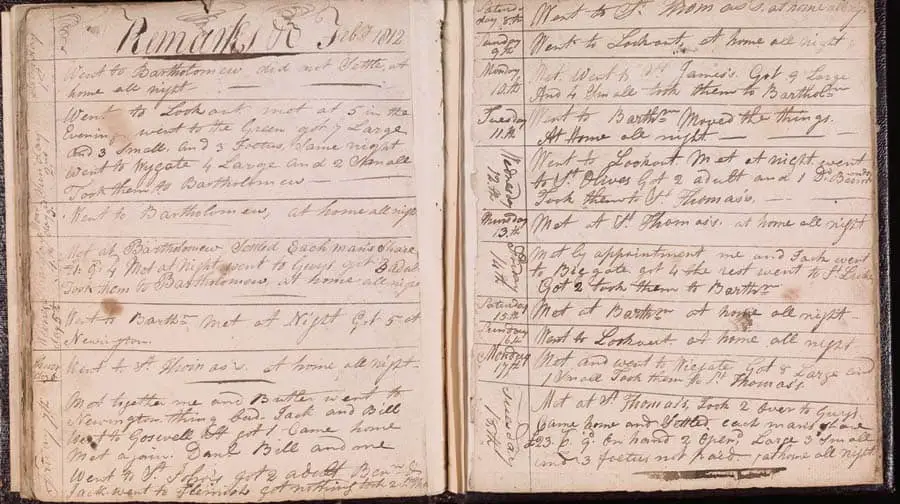

He is perhaps most famous for having kept a diary of the gang’s dealings with the London anatomists between November 1811 and December 1812.

The ‘Diary’ gives an insight into this rarely recorded period in history, detailing the money exchanged, graveyards targeted and even the names of the anatomists who were ordering and buying the corpses. You can even discover when the gang were drunk, stayed home or when the horse refused to get out of the stable.

Naples did, however, turn his life back around once the Anatomy Act of 1832 was passed and the frenzy that was once linked to body snatching had abated. He became a porter in the dissecting rooms of the very hospital to which he had been supplying cadavers, St Thomas’s.

Daniel Butler: An Original Borough Gang Member

Daniel Butler was a former superintendent of the dissecting rooms at St Thomas’s Hospital. Before he became a full-time resurrectionist, he’d helped famed anatomist Sir Astley Paston Cooper articulate the skeleton of an elephant that he had acquired from the Tower of London menagerie.

Unfortunately, lured by promises of the criminal underworld, Butler was prone to theft and was apprehended in 1803 with over £200 worth of silk on his person. Not being able to bluff his way out of his predicament, he was disgraced and losing his character was dismissed from his work.

He joined Crouch in further petty thefts before eventually entering the resurrectionist business full time.

As the dynamics of the gang changed, Butler left London and by all accounts took up the tooth trade in Liverpool. He was however never far from the restraints of the law and was apprehended when trying to use a stolen banknote that had recently been reported stolen from the Edinburgh Mail coach. This implicated him in the crime and he was sentenced to death.

While awaiting his execution he was given a horse’s skeleton to articulate after complaining of boredom in his cell. So impressed were two visiting Archdukes of Austria with his skills that they appealed for his pardon to the Prince Regent.

Breathing a huge sigh of relief, Butler was indeed pardoned on the proviso that he left the country.

He was apparently however still in London in 1825, specialising in importing the corpses of children from Dublin and selling them to a private dissecting academy in Southwark.

Patrick Murphy: ‘King of the Resurrectionists’

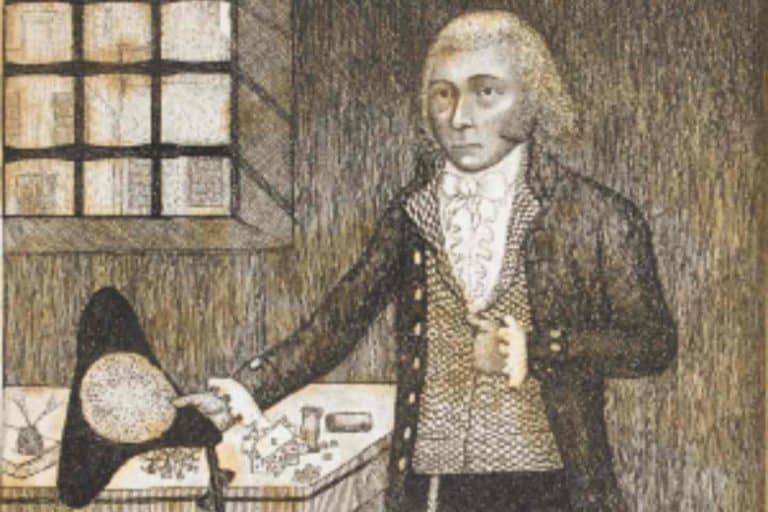

Patrick Murphy, if that was indeed his name for there is some doubt over its validity, was perhaps more ruthless than Ben Crouch. Despite this, the man who is said to have had a flat face and a good sense of humour possessed manners, something which Crouch appears to have lacked.

Murphy is first mentioned as being part of the gang at the time of the Great Cutting Scandle in 1816 and from this period grows in confidence as a key gang member.

Taking over as head of the gang, Murphy would introduce ‘finishing money’ and would almost double the price received for a cadaver. Sir Astley Cooper would later record:

On one occasion he was paid at one school £72 for six subjects and then the same evening at another school received £72 for another six subjects. Out of this Murphy would have had to pay four or five underlings in his employ but not at a higher rate than £5 each, leaving Murphy with splendid profit

You can read all about ‘finishing money’ here as well as the price of a cadaver in a post I wrote all about the dissecting season and when body snatchers plied their trade.

As Murphy’s time at the head of the gang continued, the Borough gang itself would split into two. The new leaders would be Murphy himself and Bill Hollis mentioned later in this post.

The make up of the gang now looked like this:

The Holywell Mount Affair

In the world of body snatching, Murphy is perhaps best remembered for his scourge on the burial ground at Holywell Mount, Shoreditch.

Murphy’s involvement with Mr Whacket, sexton at the private graveyard, was lucrative, to say the least with a steady source of cadavers having trickled into the anatomy schools for at least ten years.

So easy were the pickings here that rival gang members, Thomas Vaughan and Bill Hollis wanted in on the deal. Rightly or wrongly they visited Whacket to try to convince him that they should be involved in the scheme.

So persistent were they that the sexton fled to a local pub to escape and raise the alarm. Body snatchers were in Shoreditch!

The mob raised by Whacket made their way to the burial ground, right about the same time Vaughan and Hollis were running to the nearest Magistrates court to raise their own alarm.

The true extent of the deprivations was realised when coffin after coffin was unearthed and found to be empty. Whacket was arrested and Murphy’s lucrative sideline was over.

Murphy was one of the more conscientious body snatchers in that he saved the money he’d got from corpse selling and invested it in property. It is said that when he died, he left his wife and child ‘well provided for’.

But before this, Murphy would also help to ruin another body snatcher’s career, that of the other ‘King of the Resurrectionists’ William Millard.

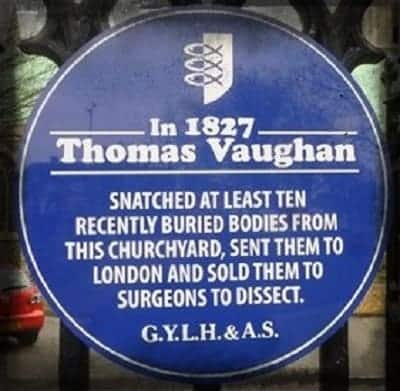

Thomas Vaughan alias Goslin

Thomas Vaughan should have known better. He was perhaps the only body snatcher to break the most fundamental rule of body snatching which resulted in him being transported along with three others to Van Dieman’s Land.

Although these rules were never written down, they were however still well known and all body snatchers, or nearly all, would have followed them. You can read more about the top five rules of body snatching in an earlier blog post of mine here.

Originally a stone mason’s labourer Thomas Vaughan joined the Borough Gang at the time of its split and ended up on the opposite side to Murphy. The pair were to have a fractious friendship ever since.

Following Vaughan’s run-in with Murphy over the Hollywell Mount Affair, he would realise Murphy’s wrath a year later he exacted his revenge and turned him over to authorities knowing that he was wanted for crimes elsewhere.

Vaughan spent the next two years in prison and upon his release in 1827 headed for Great Yarmouth. Here he remained until he was sentenced again for grave robbing, this time for stealing over twenty corpses from St Nicholas Church.

Upon his release and after a flurry of unsuccessful body snatching attempts where he was arrested and imprisoned too many times to mention, Vaughan turned his back on city life and in August 1830 moved to Plymouth, going by the name of Goslin.

For a body snatcher who had been heavily involved in the trade for over fifteen years, it is rather surprising that his ultimate downfall would be the theft of grave clothes.

When his movements were tracked by the master of a servant girl he’d tried to seduce, he was unaware that the police officer assigned to his case had recently relocated to Plymouth from London and recognised him.

A search of his home turned up stockings and a shift proven to belong to one of the cadavers recently lifted from the local churchyard.

This escalated the severity of Vaughan’s crimes and together with his wife Louisa, and two other associates, John Jones and Richard Thompson, were convicted of larceny and transported to Van Dieman’s Land for a term of seven years.

According to Brandsby Cooper’s account of Vaughan when writing his Uncle’s biography, ‘Vaughan and his wife have never returned … although the period of their banishment has long expired’.

Other Gang Members

There were other members of the gang who although active, are not as well documented in the history of the gang as the others.

Often these men, either through greed or lack of opportunity came to be members of the Borough Gang out of necessity. Their stories, however brief, are still just as interesting.

William Millard ‘King of the Resurrectionists’

William Millard started working at St Thomas’s Hospital in 1809 and in 1814 became superintendent of the anatomy theatre.

Things went smoothly for Millard but his greed and surety of himself were to be his downfall. He tried to double-cross the system, buying cadavers from Murphy and reselling them to anatomists in Edinburgh for a profit.

After refusing to accept a damaged cadaver that Murphy was selling as part of a job lot, tension between the two increased and Murphy was again determined to exact his revenge.

Millard was, of course, found out, mainly due to Murphy’s doing and with his name tarnished had to leave his position at the hospital. After a failed attempt at running a chop-house, he was forced into full-time body snatching for the same reasons as his predecessors before him; the public found out where the money to start his business had come from and refused to support his enterprise.

His attempt to break in and snatch cadavers from the London Hospital Burial Ground was to be the beginning of his ultimate demise.

Being caught by the watch rifling graves with Wildes (see above), the pair were arrested and sentenced to a three-month stint in Cold Bath Fields Prison.

His employer, Edward Grainger of Webb Street Anatomy School in Southwark, bailed him out of prison which gave him the confidence in thinking that he could accuse the constables of falsely arresting him.

This was not the case and Millard was sent back to Cold Bath Prison where he would subsequently die.

Millard’s wife Ann, did not take to her new situation favourably. Fractions between surgeons meant that any association with the school on Webb Street led to little, if any, support for the body snatcher and despite having played a part in providing subjects for the surgeons, no support was given to Millard and Ann was left to her own devices.

Ann protested in the form of a pamphlet entitled ‘An Account of the Circumstances Attending the Imprisonment and Death of the late William Millard’ exposing the full underworld of the body snatching trade.

The account also gave a few suggestions on how to fill the gap in the legal supply of cadavers; that all surgeons should agree to leave their bodies for dissection before they received their licence to practice.

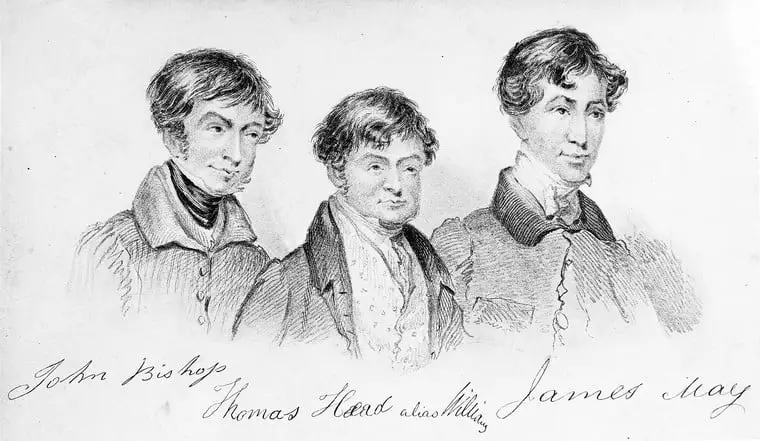

The London Burkers: Bishop, Williams & May

The last group in this short introduction to London’s most famous body snatchers perhaps need little or no introduction.

Known as the London Burkers or the Italian Boy murderers, this trio met their downfall in 1831 and was probably the driving force for getting the Anatomy Act pushed through Parliament the following August.

Often compared to the Edinburgh murders Burke and Hare, the London Burkers did something that their Edinburgh counterparts didn’t; they actually did rob a few graves.

Their downfall came with the subjects that they murdered. Drugged with laudanum and hung upside down in the well at the bottom of the garden, the victims died a horrible death.

We know of three individuals who met their end this way:

They are perhaps best known for their murder of Carlo Ferrari or as court records state ‘alternatively murdering a boy unknown’.

It was only supposition that their last victim was Ferrari, and this caveat would ensure that the murderers could still be sentenced should it be found that the body belonged to someone else.

Their base, 3, Nova Scotia Gardens where the murders took place was to become known as ‘Bishop’s House of Murder’ and it was to be the scene of intense fascination to hundreds of visitors hoping to catch a glimpse of the site where the body snatchers lived.

Not surprising really as when the house was searched, there were plenty of items found to catch the public’s imagination:

The trio was bought to trial at the beginning of December 1831 and on the 3rd December, the summing up of the trial began.

John Bishop and Thomas Williams were sentenced to death, their bodies to be publically dissected.

Bishop’s corpse was dissected at the very anatomy school that had raised suspicions as to the freshness of the cadaver. King’s College Dissecting Rooms were delighted with the condition of Bishop’s body once the dissection was underway stating that

‘A more healthy or muscular Subject has not been seen in any of the schools of anatomy for a long time’

Thomas Williams’s dissection at Great Windmill Street was a much less organised affair the Bishop’s. Students were reported to have cut off locks of his hair, keeping them as souvenirs and two students were actually seen fighting next to the corpse.

May, although receiving a last-minute reprieve, has a pretty dismal end to his life suffering in the prison hulks and dying within a year of the trial.

Researching Famous London Body Snatchers

*There are three claims to the title of ‘King of the Resurrection Men’. In his book, ‘ The Resurrection Men’ Brian Bailey say that it was Sir Astley Cooper who was known by this name due to his dealings with the body snatchers.

‘The Diary of a Resurrectionist’ is worth its weight in gold if you’re interested in reading further. The ‘Diary’ became part of a larger book written by James Blake Bailey in 1896. You can access a free online copy here via the Project Gutenberg website.

I cannot stress enough the work of Sarah Wise and her research into her book ‘The Italian Boy’ and I have relied on it for writing this section in my post. It is a superbly written account of the events at Nova Scotia Gardens, and I urge you to read it if you have not done so already. It is widely available both at Abebooks.co.uk and at Amazon.co.uk

If you’re interested in chasing the trial of the London Burkers, then the British Newspaper Archives is an excellent starting point. You can access the site here although a subscription to view the newspapers themselves is required.

Accounts of the Borough Gang and its members can also be found within the British newspapers.