Burke and Hare | The ‘Edinburgh Murderers’

This post may contain affiliate links. Please see my disclosure policy for details.

Burke and Hare — better known as the “Edinburgh Murderers” — are among Scotland’s most infamous historical figures. Yet their story is so tangled with myth that even basic facts are often blurred.

People still call them body snatchers, even though they never stole a corpse from a grave.

Then there’s William Hare’s fate — was he blinded with quicklime and left to beg in London, or did he die quietly in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania)? The records never agree.

With so many versions of events, this post pulls the key facts together to separate documented truth from long-standing myth.

If this sort of dark history interests you, then my newsletter might too. I share historical finds like this — plus historical true crime you won’t see in the history books. You can sign up here.

Table of Contents

- Who Were the Edinburgh Murderers — and What Made Them Famous?

- Is the Story of Burke and Hare True?

- Were Burke and Hare Really Body-Snatchers?

- The Birthplace of William Burke

- The Birthplace of William Hare

- What Jobs Did Burke and Hare Have Before the Murders?

- What They Did Before Arriving in Edinburgh

- The Wives of Burke and Hare

- What Happened To Their Wives?

- Did Burke or Hare Have Children?

- How Did They Meet?

- Burke And Hare’s Home in Edinburgh

- Why Did They Start Killing?

- Where Did Burke & Hare Kill Their Victims?

- What Is Burking & Where Did The Term Come From?

- How many bodies did Burke and Hare steal?

- Who Were Burke and Hare victims?

- Arthur’s Seat Coffins, Edinburgh’s Miniature Coffins

- Where Did Burke And Hare Sell The Bodies?

- Dr Robert Knox: The Anatomist Who Purchased The Bodies

- How Much Money Did Burke and Hare Make?

- Mary Docherty, Burke And Hare’s Last Victim

- How Was William Burke Caught?

- How was William Hare Caught?

- What Happened to Them When They Were Caught?

- Where is William Burke’s Body?

- What Happened To William Hare?

- The Burke And Hare Rhyme

- Burke & Hare Recommended Reads

Who Were the Edinburgh Murderers — and What Made Them Famous?

Burke and Hare were two Irish immigrants who became Edinburgh’s most notorious serial killers, murdering at least sixteen people between 1827 and 1828.

They are remembered for two things — their murders, and the persistent but false claim that they were body snatchers.

Their victims were the poor and vulnerable, whose bodies they sold to the anatomist Dr Robert Knox for dissection at his anatomy school in Surgeons’ Square, Edinburgh.

Today, Burke and Hare remain Scotland’s most infamous murderers. Their story still features on Edinburgh ghost walks, in films, and across countless books and articles.

Despite the fascination, surviving archival evidence about the pair is thin — meaning much of their real character remains uncertain even now.

Is the Story of Burke and Hare True?

Yes. Burke and Hare were real men who murdered at least sixteen people in Edinburgh between 1827 and 1828, until finally being caught on All Hallows Eve,1828.

They sold the bodies to Dr Robert Knox for about £10 each. Burke was hanged on 28 January 1829.

The case — known at the time as the West Port Murders — became one of Scotland’s most notorious serial-killing scandals.

Public outrage over the murders helped spark early debate that led to Britain’s Anatomy Act of 1832.

Burke and Hare didn’t directly cause the Act — that credit went to the London ‘Burkers’ (Bishop, Williams and May 1831) — but their crimes began the conversation that made reform inevitable.

Much about who they really were remains unclear, but what’s known — and the myths that followed — are gathered here.

Were Burke and Hare Really Body-Snatchers?

No — Burke and Hare were never body-snatchers.

They supplied corpses for dissection by murdering their victims, a method later called “Burking.” They gained the label only because they sold the bodies to anatomy schools, but there’s no evidence they ever dug up a grave.

In his Courant confession, Burke stated clearly that neither he nor Hare ever stole from graves.

He repeated this in his official confession on 22 January 1829, declaring that‘neither he nor Hare, … had supplied any subjects for dissection except those he mentioned, and had never done so by raising dead bodies from the grave’.

Like Bailey says in his book Burke and Hare: The Year Of the Ghouls, but grave-robbing wasn’t it.

Burke stayed firm on that point until the end, insisting they never touched a buried corpse.

With no physical or testimonial evidence to the contrary, historians agree that Burke and Hare were killers — not body snatchers.

The Birthplace of William Burke

William Burke was born in Ireland in 1792, often said to be in a place called “Orrey” in County Cork.

He came from a Catholic family and moved to Scotland in 1818 to work as a navvy on the Union Canal. That same year he met William Hare — the partnership that would make them Scotland’s most notorious killers.

The exact location of Burke’s birthplace is uncertain.

Owen Dudley Edwards, in ‘Burke and Hare’ argues that “Orrey” was a mishearing of Urney in Strabane, County Tyrone — the “n” lost through Burke’s accent and later repeated as fact.

Some sources place his birth in Poyntzpass, on the Armagh-Down border, and suggest he was born in 1804 rather than 1792 — which would make him only twenty-four during the murders.

In his first confession (3 November 1828), Burke gave his age as thirty-six — a detail Edwards and most historians accept as accurate.

The Birthplace of William Hare

William Hare was born in Newry, County Down, though his birth year is unknown.

He came to Scotland in 1818 to work as a navvy on the Union Canal — the same year as Burke — and later received immunity for his role in sixteen murders committed in Edinburgh between 1827 and 1828.

Hare’s early life remains elusive; most of what is known comes from trial evidence.

Contemporary accounts describe Hare as ‘uncouth, violent and quarrelsome’ — the opposite of Burke, who was considered ‘pleasant enough company and skilled with a spade’.

What Jobs Did Burke and Hare Have Before the Murders?

Before turning to murder in 1827, both Burke and Hare worked as navvies on the Union Canal, which linked Edinburgh to the Forth & Clyde Canal at Falkirk.

Burke had previously served in the Donegal Militia, while Hare’s earlier life is vague — possibly including time in the Irish militia.

The Union Canal took four years to complete, and both men are believed to have worked on it throughout.

After the canal work ended, Burke drifted between Leith and Peebles, hawking old clothes and taking occasional farm labouring jobs.

He also learned cobbling, a trade he used to earn money in his early days with Hare.

What They Did Before Arriving in Edinburgh

Before coming to Scotland, Hare may have been working seasonally in the hop fields of Kent, while Burke was still serving in the Donegal Militia.

Edwards suggests this could explain the gaps in Hare’s record before 1818.

Little else is known about Hare’s early years; some believe he also joined a militia, though no record survives.

The Wives of Burke and Hare

William Burke was already married when he came to Scotland in 1818, but his wife, Margaret Coleman, stayed in Ireland with their children.

In Edinburgh, Burke began living with Helen (“Nelly”) McDougal. Hare, meanwhile, pursued Margaret Laird — wife of his landlord, James Logue — and married her after Logue’s death in 1826.

Burke’s first wife, Margaret Coleman, likely counted herself lucky to have stayed in Ireland; by 1829 she’d have seen what she escaped.

The domestic lives of both couples were violent and chaotic, with sources describing frequent drunken fights and signs of abuse.

Both women appear to have given as good as they got; drink and volatility ran through both households.

Despite their apparent devotion, violent quarrels were common.

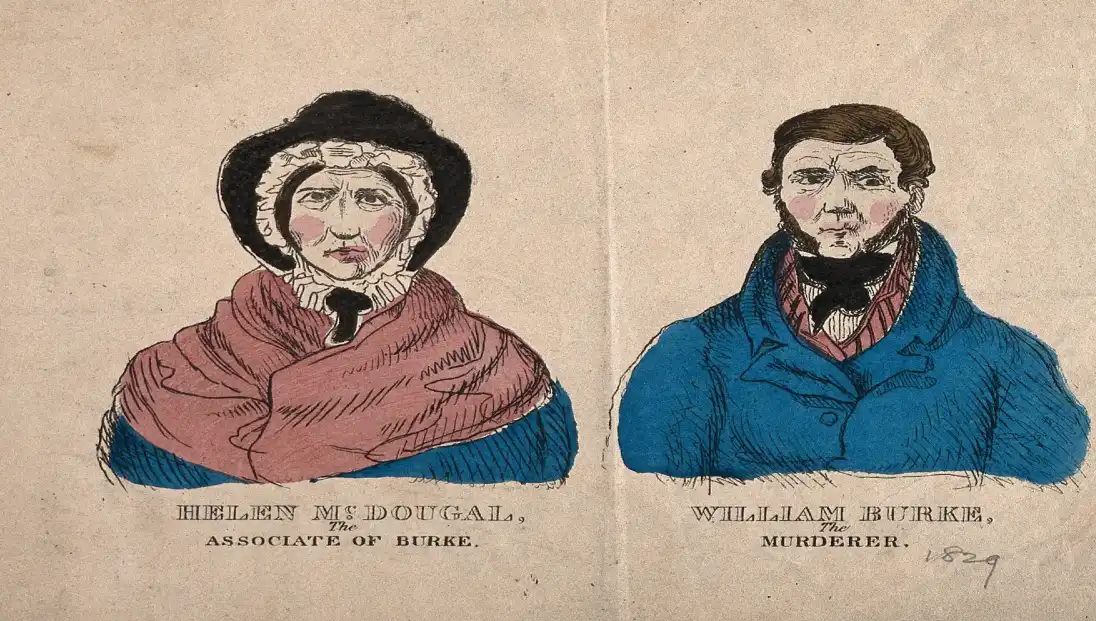

William Burke’s Wife,‘Nelly’ McDougal

William Burke deserted his first wife, Margaret Coleman, to pursue a better life in Scotland, and ultimately Edinburgh and it was while working on the Union Canal that Burke met Helen, also known as ‘Nelly’ McDougal.

Helen McDougal, an illiterate Scot from Redding near Falkirk, was already in a relationship with another by the time she met Burke. Authors have suggested that she may have been one of the many prostitutes following the navvies as they progressed with their work along the Union Canal.

Absconding with Burke to Edinburgh in 1827, Nelly took her two children with her.

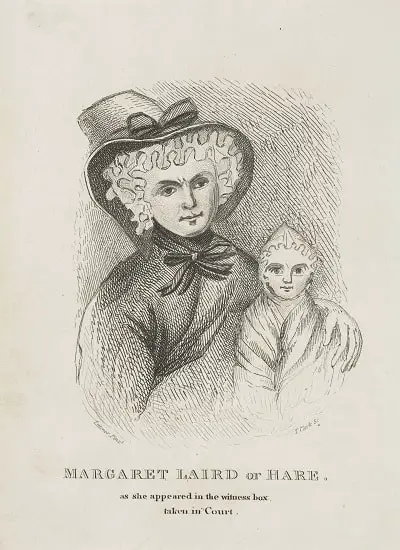

William Hare’s Wife, Margaret Laird

William Hare lost no time in pursuing the wife of his landlord, James Logue, after he took rooms in his lodging house in Tanner’s Close, Edinburgh.

Nicknamed ‘Lucky’, Margaret Laird had also worked as a navvy on the Union Canal, donning men’s attire to blend in with the other men.

Her character has been described as hard-featured and, according to Bailey a ‘debauched virago’, which, after a quick lookup, means she was showing ‘abundant masculine virtues’.

I imagine a woman who could certainly hold her own, taking no nonsense from anyone. It sounds like Laird and Hare were well matched and accounts state that she was ‘often brutally intoxicated and seldom without a pair of black eyes’.

Following Logue’s death in 1826, Hare quickly returned to the lodging house where his sweetheart lay and immediately started wooing the woman and moving in, acquiring ownership of the property in Tanner’s Close in the process.

What Happened To Their Wives?

The wives of both William Burke and William Hare were released following the trial in December 1828. Burke’s wife, Helen McDougal was recognised by a mob after returning back home and is rumoured to have been seen in the North East of England before dying in Australia in the 1860s. Hare’s wife, Margaret Laird is said to have secured a passage on board the Fingail, sailing to Belfast. She was possibly sighted in Paris in the 1850s working as a nursemaid.

William Burke insisted that his wife Helen McDougal was innocent throughout the ten-month killing spree, insisting on her innocence all the way to the scaffold. However, there is evidence to suggest that she was more involved in events than perhaps Burke let on.

Described as having a ‘dull morose disposition’, it is believed that the pair had a genuine affection for each other despite the battles between them that ensued on Edinburgh’s streets.

One fellow Irishman, James Maclean, goes so far as saying that ‘the pair led a most unhappy life, everlasting quarrelling’.

But this most unhappy life was filled with a darker side, one which by the time McDougal stood trial in court, was being venomously denied.

The Trial of Burke’s Wife, Helen McDougal

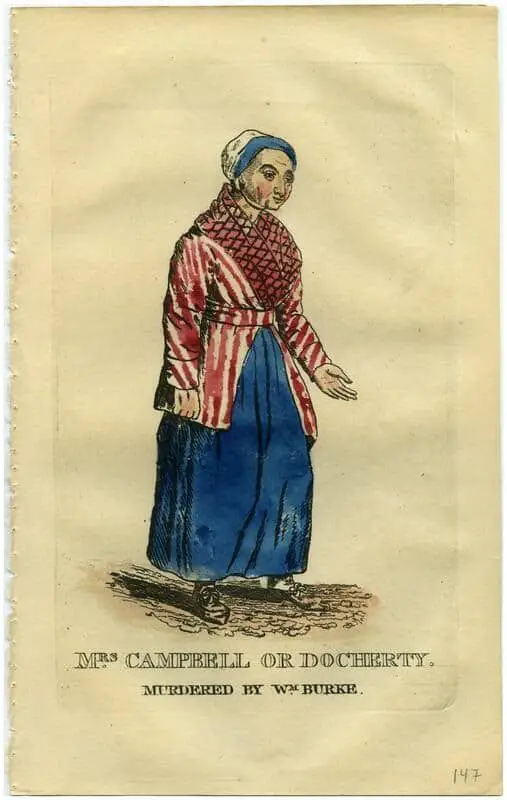

William Burke’s wife, Nelly McDougal, appeared in the dock on Christmas Eve/Day 1828 to hear if she was to be found guilty of being an accomplice in the murder of Margaret/ Mary (also known as Madge) Docherty, Burke and Hare’s last victim.

The jury heard how McDougal, had tried to bribe Mrs Gray, their lodger, who had unfortunately discovered the naked body of murdered Mary Docherty under a pile of straw at the foot of Burke’s bed.

Meeting on the stairs in the narrow passageways surrounding Burke’s lodging house, Nelly pleaded with Mrs Gray to ‘hold her tongue’ at what she had just discovered.

It could be worth up to £10 per week to her she said, if she would say no more about the body. But alas, the Gray’s could not be bought.

It took just 50 minutes for the jury to reach their verdict of ‘Not Proven’, to which Burke turned to his wife saying ‘Nelly, you’re out of the scrape’.

From here, both Burke and Nelly were taken to Parliament House where they remained for the rest of the day. Early Boxing Day morning, the pair journeyed to Calton Jail where Burke was escorted immediately into the condemned cell.

Nelly McDougal Leaves Edinburgh

Nelly McDougal was sent to Falkirk the day after being recognised on the streets of Edinburgh, but little good it did her.

She immediately returned to Edinburgh to try to see Burke in his cell at Calton Jail but was denied a visit.

From here, her journey gets sketchy.

Seen in Newcastle, she was then sent further south to the Durham border as neither parish wanted anything to do with the woman who was so obviously implicated in the Burke and Hare murders.

Just like Hare, McDougal disappears from history with unrefuted claims that she died some forty years later in Australia.

William Hare’s Wife, Margaret Laird, Appears In Court

When it came to Margaret Laird’s turn in the witness stand she arrived clutching her child tight to her breast.

Whether a decoy or from real maternal instinct, the child that Laird had with her that day was suffering from whooping cough and she used the numerous coughing attacks as thinking time before answering any of the judge’s questions.

Laird admitted to leaving the house with McDougal as Burke was killing Docherty. For a full 15 minutes, she claimed to be away and upon her return, the ‘old woman’ (as Hare recalled her) Mary Docherty, was gone.

And as simple as that, Margaret Laird, wife of serial killer Wiliam Hare, went to bed.

Most commentators of Burke and Hare agree that Margaret Laird knew about the murders but chose to keep quiet. How could she not, many were committed under her roof, in fact, that was where it all started.

Although she may not have taken part in the actual act, she still benefitted from the murders for she always took £1 from the proceeds received by Knox to cover ‘the use of her house’.

The Immunity Of William Hare’s Wife, Margaret Laird

The minute William Hare agreed to turn King’s evidence, any possible prosecution against his wife had to be dropped for Hare could not testify against his own wife.

After being examined a total of three times on the stand, as well as being questioned about her part in the murder of Jamie Wilson, known forever in history as ‘Daft Jamie’, Margaret Laird was eventually released on 19th January 1829.

Perhaps not knowing what to do or where to go, she headed home. She was immediately recognised in the Old Town and set upon with mud and stones until the police came and took her in for her own protection.

Two weeks later, Laird resurfaced in Glasgow, where she was again recognised. Help eventually came on 12th February when authorities managed to secure her a passage on board the Fingail, a ship sailing from Greenock to Belfast.

Another elusive character, Laird then disappears. But Bailey, in his book ‘The Year of the Ghouls’ mentions a curious sighting of her some thirty years later when she turns up as a nursemaid in Paris.

I agree with Bailey that this is probably highly unlikely and goes completely against her supposed wish of living out her days in the remote Irish countryside.

Did Burke or Hare Have Children?

Both Wiliam Burke and William Hare had children. William Burke’s natural children remained in Ireland with his first wife when he came to Scotland in 1818. Hare’s only child with Margaret Laird is surrounded by uncertainty. Available sources cannot confirm whether the child was Hare’s, or a young child of James Logue, Laird’s first husband.

William Burke’s two children with his first wife Margaret Coleman, remained in Ireland with their mother when Burke decided to try his luck on the Canal and hopped over to Scotland in 1818.

Nothing further is known about either of them.

Helen McDougal, Burke’s common-law wife, already had two children with the man she was with before Burke but again, nothing more is known about them apart from this.

William Hare on the other hand may or may not have been the natural father of Laird’s sickly child that she carried into court. Although modern authors suggest that the child is Hare’s, conceived relatively quickly after Logue’s death.

How Did They Meet?

Despite both men being employed as navvies on the Union Canal, Burke and Hare didn’t actually meet until Burke and his common-law wife, Helen, ‘Nelly’, McDougal rented a room in Hare’s lodging house on Tanner’s Close, Edinburgh in November 1827.

It was quite by chance that Burke stumbled upon Hare for he was about to leave Edinburgh with ‘Nelly’ and try his luck as a cobbler elsewhere, out of the city.

As luck would have it, fortune was smiling on the two this day for they bumped into Hare’s common-law wife, Margaret Laird.

In an act that seems all too familiar in the story of Burke and Hare, the meeting happened by accident in the street.

Telling their story of woe to Laird, she immediately invited them to become her lodger, as quite by chance, a room had become vacant at the lodging house her husband Hare owned in Tanner’s Close.

I have also read that the pair met in Penicuik, just under 10 miles (16km) miles outside of Edinburgh while working as general farm labourers and that they travelled to Edinburgh together.

The consensus, however, is that they met in Edinburgh when Burke and Nelly bumped into Laird. In reality, we may never know in truth how the pair came to meet.

Burke And Hare’s Home in Edinburgh

Burke and Hare lived in two places in Edinburgh. Initially, they both lived in Tanner’s Close where Burke was Hare’s lodger. By the summer of 1828, after a disagreement over Hare selling a body while Burke was away in Falkirk, the pair had split and Burke moved in with his cousin, John Broggan, just two streets away.

Where Was Tanner’s Close in Edinburgh?

Tanner’s Close was situated in the West Port, a slum of a place in a city that was vastly overcrowded. Hare’s lodging house was at the bottom of Tanner’s Close. Demolished in 1903, the site is now occupied by Argyle House.

You may also have heard Hare’s lodging house in Tanner’s Close being referred to as Logue’s House. But who was Logue and how did Hare come to be in possession of his property?

Before Hare got his hands on the property, James Logue ran the lodging house in Tanner’s Close with his wife, Margaret Laird.

When Hare became a lodger, it wasn’t long before he turned his attention to Logue’s wife, an act that resulted in Logue kicking him out of his lodgings.

Logue died in 1826 and Hare wasted no time in pursuing Margaret. In doing so, he worked his way not only into Maggie’s heart, and bed but also into ownership of the lodging house.

I doubt any official paperwork was settled and Hare, being Hare, just presumed he could assume the status of the landlord.

Why Did They Start Killing?

Burke and Hare started murdering people after they sold the body of, Donald, ‘The Old Soldier’ to Dr Knox when he died owing them £4 rent money. Realising that good money could be made from selling corpses, the pair embarked on a ten-month murder spree making over £120 before they were caught on All Hallows Eve, 1828.

It’s still open to debate as to whether Burke and Hare murdered Donald ‘The Old Solider’, or whether he did actually die of natural causes.

Cutting out the middleman, Burke and Hare realised that they could be onto a scheme that couldn’t possibly go wrong.

If they had not been so bold as to murder Mary Paterson or kill ‘Daft’ Jamie Wilson, people may not have started to become suspicious of their actions.

The fact that people were asking questions as to the origin of some of the corpses surely indicates that their killing venture could not have gone on for much longer.

Had Mary Docherty not bellowed at the top of her lungs ‘For God’s sage get the police, there’s murder here’, would neighbours have turned a blind eye?

Would their lodgers, Ann and James Gray have been curious as to the whereabouts of the ‘old woman’ if she had had a less notable stay at Burke’s house, instead of slipping quietly away?

Where Did Burke & Hare Kill Their Victims?

All bar one of Burke and Hare’s victims were murdered either in Hare’s lodging house in Tanner’s Close, Edinburgh or at Burke’s House a few streets away. Mary Paterson/ Mitchell was murdered at Burke’s brother’s house in Gibb’s Close, Edinburgh. All the victims were suffocated, a murder method later known as ‘Burking’.

The killings started in Hare’s lodging house on Tanner’s Close, a place also referred to as Logue’s house as he was the original landlord before Hare took over following his death in 1826.

It wasn’t until Burke and his common-law wife Helen McDougal returned home from visiting her family in Falkirk in the summer of 1828 that the killings were carried out in two places.

Having his nose pushed out of joint while they were away after discovering Hare had killed without him, Burke left the lodging house on Tanner’s Close and instead took up lodgings with his cousin John Broggan a few streets away.

Only one victim was killed away from the usual place of murder and that was Mary Paterson, also known as Mary Mitchell.

Mary and her friend Janet Brown were lured to the home of Constantine Burke, William’s brother, in Gibb’s Close, off the Canongate in Edinburgh after they’d met Burke in Swanston’s shop.

Once in Gibb’s Close, they were plied with drink in preparation for being killed.

Mary’s friend Janet proved especially hard to intoxicate and left, unknowingly leaving her friend to face her fate.

What Is Burking & Where Did The Term Come From?

Burking today means ‘murder by suffocation’ so that if detected, it leaves no marks. It is the term used to describe the killing method of William Burke, the Edinburgh murderer. Burking started to appear in newspapers following his execution in 1829 and the hype became known as ‘Burkophobia’ or ‘Burking Mania’.

Following William Burke’s execution, the newspapers began to be filled with stories of people being ‘Burked’. Any attempted assault or even robbery would be reported as an attempted burking.

There are lots of reports where the intended victim has been approached from behind and a pitch plaster attempted to be slapped over their face. As Richardson has pointed out in ‘Death Dissection for the Destitute’ the period between Burke’s hanging and the publication of his confession, rumours began to spread like wildfire about the murder method.

One of these rumours was that Burke and Hare would use a medical pitch plaster to clap over the mouths of their victims, which of course we now know is not true.

For a more in-depth look at this phenomenon, take a read of my post ‘The Simple Art of Burking’

How many bodies did Burke and Hare steal?

Burke and Hare didn’t steal any bodies and are often misquoted as being body snatchers. They got bodies for sale by murdering victims they found on Edinburgh’s streets. They would then sell them to the anatomist Dr Rober Knox in Surgeons’ Square for use in his dissection classes. In total, they killed 16 people, none of which were stolen from the grave.

Sorry to disappoint you, but despite what you read on parts of the internet, these two men just weren’t body snatchers, and they couldn’t see the point of getting their hands dirty by exhuming a corpse from a grave.

To them, a quicker and more lucrative way of making a profit was by simply acquiring cadavers through murder.

Who Were Burke and Hare victims?

Burke and Hare murdered at least 16 people, taking destitute individuals from the streets of Edinburgh. Their first cadaver was ‘Old Donald’, an army pensioner who’d died owing the pair £4 in rent. Their other victims included ‘Daft Jamie’ and ‘the old woman’, Mary or Margaret Docherty, the pair’s last victim.

The first cadaver Burke and Hare sold to Dr Robert Knox in Surgeons’ Square, Edinburgh wasn’t actually murdered by them. Instead, ‘Old Donald’ died naturally while still owing rent money and his body was sold to try to recoup their losses.

Of all the people murdered, Burke was always a little unclear as to who was murdered, something which is apparent when reading both his official confession and that for the Courant.

In my larger post where I looked at the murder victims in some detail, I reproduced a table from Brian Bailey’s A Year of The Ghouls’ where he lists all the victims in order as they were recalled by Burke, or recounted by historians.

You’ll see that it differs quite a bit, depending on what account you read.

Arthur’s Seat Coffins, Edinburgh’s Miniature Coffins

In June 1836, a set of seventeen miniature coffins, complete with carved wooden figures were discovered on the northeast side of Arthur’s Seat, Edinburgh. Although only eight survive today, the origin and purpose of the Arthur’s Seat Coffins are still completely unknown but they have been linked to the victims that Burke and Hare murdered between 1827 and 1828.

These unusual artefacts, now kept at National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh, measure between 3.7 – 4.7 “ in length, with a tiny 0.8- 1.0” in depth.

After their discovery by a group of schoolboys during the summer of 1836, like all things relating to Burke and Hare, speculation as to the origin of these intriguing coffins holds no bounds.

A few of the other thoughts as to their purpose include:

Again, I’ve written a larger post specifically on the Arthur’s Seat Coffins where I’ve collected all the different theories surrounding the coffins, referencing work carried out and detailed in the Smithsonian Magazine.

Can you believe that we nearly lost all of the coffins had it not been for the quick thinking of the boy’s schoolmaster Mr Ferguson, also a member of the local Archaeological Society, who realised that there could be some significance as to what they’d found.

Before this, the boys were actually throwing them around and ‘pelted them at each other as unmeaning and contemptible trifles’.

Where Did Burke And Hare Sell The Bodies?

Burke and Hare sold the bodies of their victims to Dr Robert Knox at 10 Surgeons’ Square, Edinburgh after they were directed there by a medical student they’d met in College Yard.

Their original intention, when getting rid of the body of ‘Old Donald’, their first cadaver, was to sell it to anatomists at Edinburgh University. However, being new to the trade, they didn’t know where to go or how to find Professor Monro, their intended client.

As they were passing through College Yard, they met a medical student and nervously asked for directions. The student quite clearly knew that they had a body to sell and instead of directing them to Monro’s rooms, they instead set the wheels in motion for Edinburgh’s most prolific murderers and directed them to the dissecting rooms of Dr Robert Knox.

Although Professor Monro may have missed out on fresh cadavers, he instead not only avoided being implicated in a murder investigation but also had the honour of dissecting Burke after he’d been hanged.

Dr Robert Knox: The Anatomist Who Purchased The Bodies

Dr Robert Knox purchased all of the sixteen bodies that Burke and Hare killed, handing over a total sum of £102.10s. Dr Knox ran a private anatomy school at No.10, Surgeons’ Square which proved very popular with the medical students of Edinburgh.

What was Dr Knox Famous For?

Dr Robert Knox (1791-1862) is famous not only for being the Scottish anatomist who bought the bodies from murderers Burke and Hare, but also for being an excellent surgeon and lecturer. He studied medicine at the University in Edinburgh in 1810, becoming principal of Barclay’s extra-mural anatomy school at 10 Surgeons’ Square, Edinburgh in 1826.

Knox’s career was, and is, overshadowed by his involvement with Burke and Hare. Surprisingly, despite his obvious guilt, Knox was never prosecuted for his role in the crime, although his career would never fully recover from his involvement in the scandal.

What happened to Dr Knox?

Following the trial of Burke and Hare in 1828, Dr Knox remained in Edinburgh with a tarnished character.

To say Knox was hated by the Edinburgh mob would perhaps be an understatement. On the night of 12th February 1829, a large crowd made their way to Knox’s house from Calton Hill carrying a life-size effigy of Knox. Attached to the waistcoat was a label with the writing ‘Knox, The Infamous Associate of the Infamous Hare’.

In Rae’s book ‘Knox The Anatomist’, she states that Knox refused to be intimidated by the mob, continuing to lecture as before to an ever-adoring student crowd.

He would finally leave Edinburgh in 1842 following his wife’s death and try for a new life in London. It would be fourteen years before Knox gained another position in the dissecting rooms. He was appointed pathological anatomist of the Cancer Hospital in London, on 23rd September 1856.

Knox died following an apoplectic seizure on 20th December 1862.

How Much Money Did Burke and Hare Make?

Burke and Hare made £102.10s between December 1827 – October 1828. The average price they received for each of their victims was £10. The least amount was £5 for Mary or Margaret Docherty, their final victim. They squandered all the money they made on drink and fine living.

The pair were making good money, and they knew it. It’s the thing that drove them to kill, together with the fact that they may have started enjoying it.

How Much Money Did they Make For Each Body?

Burke and Hare made an average of £10 per cadaver sold to Dr Knox. Knox had both a summer and winter rate at which he bought cadavers and most of Burke and Hare’s victims were murdered during the winter months. Cadavers sold to Knox during the summer months would make an average of £8 each.

It was a well-known fact in 19th century Scotland, and elsewhere, that a cadaver didn’t last very long during the warmer summer months.

What is known as the ‘dissecting season’, that is the period between October to May when the majority of students were studying anatomy, cadavers would have been in high demand. Dr Knox would have wanted to maintain both his reputation as an excellent teacher and as an anatomy school that provided an ample supply of teaching material for his students.

During the quieter summer months, dissections still took place, although not in the quantity that they would do during the colder winter months. The price naturally fell as demand fell, and unless the specimen had particularly unusual features or ailments, then it would have been hard to negotiate steeper terms.

Knox paid a good price for a cadaver, especially fresh ones like those delivered by Burke and Hare. If you want to explore further, then have a look at my larger post on how much money Burke and Hare make.

Mary Docherty, Burke And Hare’s Last Victim

Burke and Hare’s last victim was Mary or Margaret Docherty, also known as ‘the old woman’. She was killed on All Hallow’s Eve, 31 October 1828 and her body hidden under a pile of straw at Burke’s house. After getting Docherty drunk, she was suffocated by a method now referred to as ‘Burking’, that is by placing a hand over the nose and mouth of the victim.

Burke and Hare’s final victim, known by a variation of her Christian name Margaret, (Mary/Madge being the most common) is often referred to as ‘the old woman’. This name appeared after Hare sought clarification on the witness stand as to which victim he was being questioned about.

Lured back to Burke’s lodging house on the promise of food and drink, the unfortunate Docherty fell for the rouse that Burke was in fact a kinsman and that would you believe it, his mother also came from the small town of Inishowen.

Quite forgetting that she’d come to Edinburgh from Glasgow to look for her son, Mary Docherty wandered quite freely into one of Burke and Hare’s lairs.

How Was Burke & Hare’s Last Victim Murdered?

Mary Docherty was murdered after being plied with whisky at the home of William Burke, a few streets away from Hare’s lodging house in Tanner’s Close.

It was during this drunken stupor, as she lay unconscious on the floor that the ‘old woman’ was murdered by a murder method known as ‘Burking’

.A hand was clasped over her mouth and nose and she was held down by her chest.

Her body was then stripped naked, folded into half or threes and stuffed under a pile of straw at the edge of the bed. Docherty would later be found by Burke’s lodger, Ann Gray, when she returned home for breakfast.

A sad story indeed for Mary was only seeking comfort from a fellow countryman. You can read more about Burke and Hare’s last victim, Mary Docherty in the link to my larger post.

How Was William Burke Caught?

William Burke was caught for the murders he committed when his lodger, James Gray informed the police that he had found the dead body of Mary Docherty hidden under straw at Burke’s property on Tanner’s Close.

If it hadn’t been for Burke’s strange behaviour – he started splashing whisky around the room to mask any odours – or the fact that Burke and Hare’s wives had tried to buy the silence of lodgers Mr and Mrs Gray, then they may have been able to get away with murder for a little while longer.

William Burke would eventually be arrested and taken into custody when Sergent Fisher, having turned up at Burke’s house with James Gray, became suspicious of the discrepancies in the stories given to him by Burke and his wife Nelly McDougal.

Neither could account for the whereabouts of the ‘old woman’ Mary Docherty, which, together with bloodstains being found on the bedclothes at Burke’s house, was enough to raise suspicions. Both Burke and McDougal were taken into custody.

How was William Hare Caught?

William Hare was caught for his part in the Edinburgh murders after Sergeant Fisher called at Surgeons’ Square and saw the body of Mary Docherty bound up in a tea chest.

The body was identified by James Gray as that he’d seen hidden under the straw at Burke’s house.

Burke and his wife Nelly denied all knowledge of the corpse, presumably laying events onto Hare at this point. The police made their way to Tanner’s Close where Hare and his wife Margaret Laird were arrested and taken into custody.

What Happened to Them When They Were Caught?

Burke and Hare, together with their wives Helen McDougal and Margaret Laird were all in custody by 2nd November 1828. They were charged with murder later that day and brought before the Sheriff-substitute Mr George Tait to make a statement. They were held in Calton Jail before their trial which was heard on Christmas Eve, 1828.

Not one of the four statements matched, Burke conjuring up a story that he’d been asked to look after the tea chest by a gentleman whose shoes he was repairing.

It was only when he looked in the chest, he claimed, that he saw the body which bore no resemblance to the body that he was shown at the police station.

Further statements were made a week later by both Burke and his wife, where Burke changed the details of what had happened that night saying that he and Hare had found Docherty lying dead under the straw, presumably suffocating herself where she fell asleep intoxicated, head down in the straw.

Burke and Hare’s case was held at 10 o’clock on Christmas Eve 1828 in Parliament Square, Edinburgh before the High Court of Justiciary.

Did they hang?

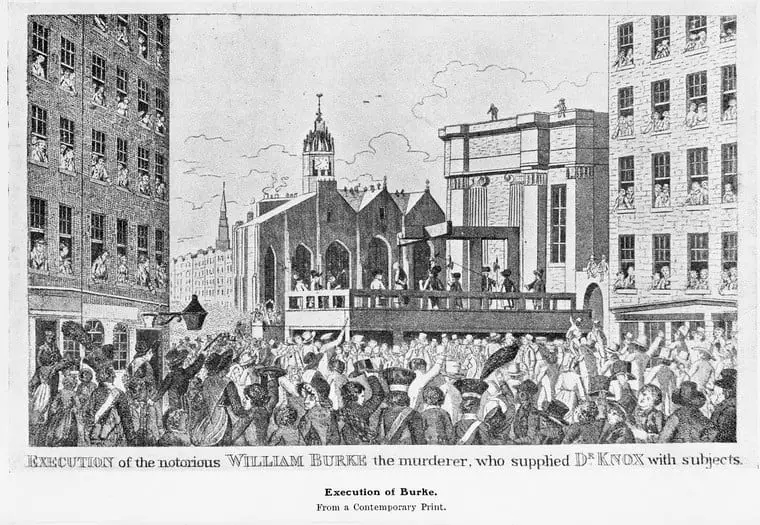

Only William Burke was hanged for the murders that he committed with William Hare between 1827 and 1828. William Burke was hanged in Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket on 28th January 1829 in front of a crowd of over 25,000 people. William Hare was given immunity after turning King’s Evidence. His whereabouts after the trial remain unknown.

Much to the crowd’s disgust, only William Burke was hanged for the awful murders that took place in ten months that he and Hare roamed the streets of Edinburgh.

How was William Burke executed?

William Burke was executed by hanging and then sentenced to be anatomised in accordance with the 1752 Murder Act; An Act For Preventing The Horrid Crime of Murder. His body was publicly dissected by Professor Monro at Edinburgh University Medical School.

Burke’s hanging took place at 8.00 am on the morning of 28th January 1829 in front of the biggest crowds that Edinburgh had ever seen.

The Lawnmarket, where Burke’s scaffold had been erected was bursting with people trying to catch a glimpse of this murderer and when the crowd saw him, they immediately started to call for Hare and Knox to be hanged as well.

We all know that this didn’t happen and the unjust feeling that must have run through Edinburgh at this time must have been extraordinary.

Accounts say that Burke walked quickly up the scaffold steps and struggled little when the steps were pushed away and he was launched into eternity. His body was then coffined and conveyed to an awaiting Professor Monro.

Where is William Burke Buried?

William Burke doesn’t have a burial place. Following his execution by hanging at Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket on 28th January 1829, he was sent to be anatomised by the surgeons at Edinburgh University, and dissected by Professor Monro. His skeleton now hangs in the Anatomical Museum, Teviot Place, Edinburgh.

On 26th March 1752 the Act, ‘for better preventing the horrid crime of murder’, better known as ‘The Murder Act’ came into force.

Included in the text were the words ‘that some further terror or peculiar mark of infamy be added to the punishment’ … ’and that in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried.

This allowed Lord Justice-Clerk to stipulate that the murderer either be placed in a gibbet or be subjected to a public dissection following execution. In Burke’s case, it was the latter, and he was sent to the dissecting rooms at Edinburgh University where Professor Monro was waiting.

Where is William Burke’s Body?

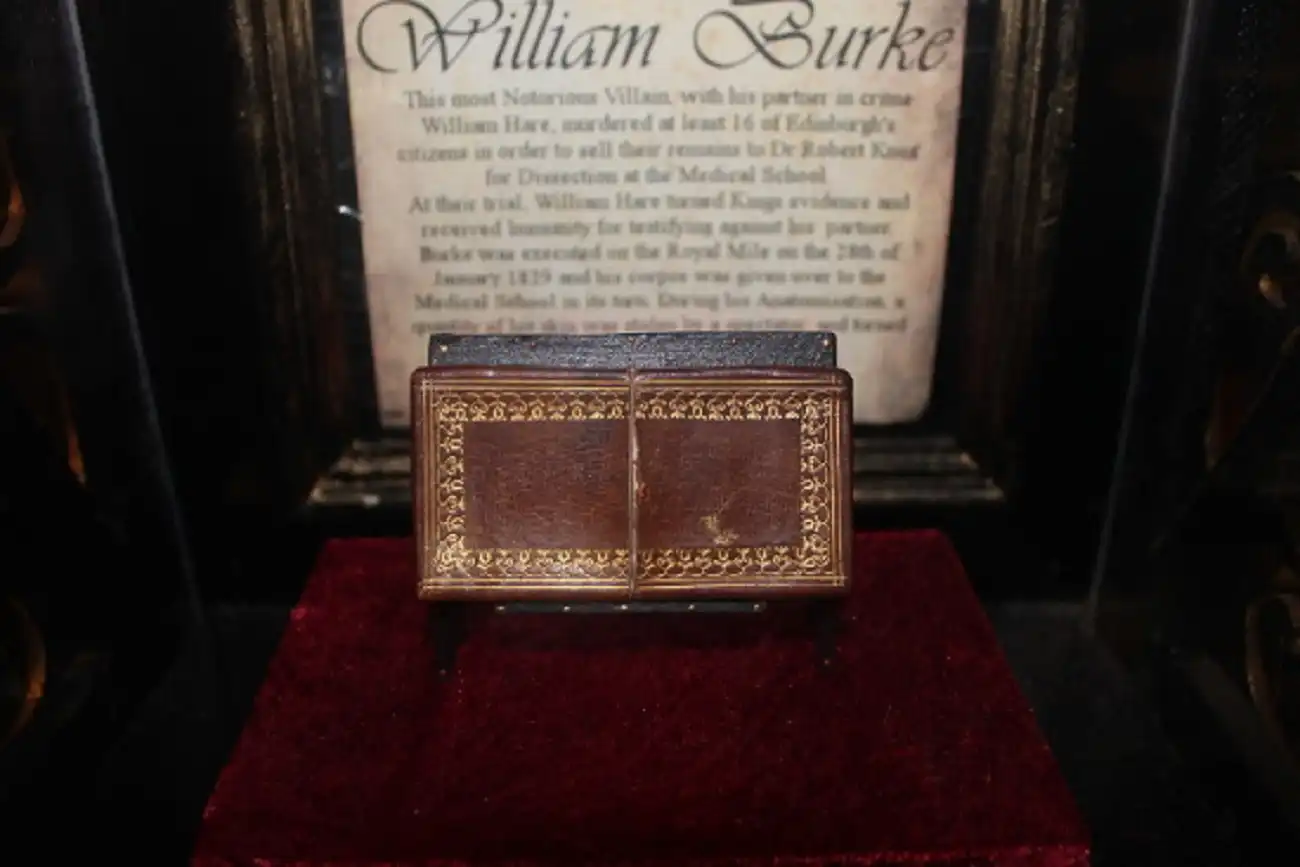

As part of his death sentence, William Burke was anatomised and his skeleton is now on display at the Anatomical Museum, Teviot Place, Edinburgh. Parts of William Burke’s body can also be found at Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh, where a pocketbook was made from his tanned skin and a calling card case, also covered in his skin can be found at The Cadies & Witchery Tour Shop. A piece of his brain is in a jar at The Science Museum, London.

This man is certainly dotted around the county and since writing my post Finding William Burke: The Relics of A Murderer, I’m quite surprised at how far and wide this guy has actually gone.

The most famous of all the William Burke relics are perhaps his skeleton and the pocketbook made from his tanned skin.

They’re kept in two very different places. William Burke’s skeleton now hangs in a display case in the Anatomical Museum at Teviot Place, Edinburgh and the pocketbook at Surgeons’ Hall.

But don’t go racing off too soon, Burke’s skeleton could once only be viewed on selected days. Full details about openings etc. can be found on their website

William Burke at Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh

Hot footing it off to look at the pocketbook made from Burke’s skin is a different matter entirely and the book is currently on permanent display at Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh.

Alongside the pocketbook is a ‘death’ mask, hotly disputed to be such by the human remains conservator at Surgeons’ Hall, Cat Irving. Even with my rudimentary anatomical knowledge, I can understand why.

Cat has suggested that there is muscle tension showing in the facial muscles on Burke’s face and that this wouldn’t be present if he were dead. Also, and I think this is an equally viable reason, if there is a life mask of Hare, then why wouldn’t they have taken an impression of Burke at the same time?

I love that nearly 200 years later, we’re still talking avidly about this pair and questions such as this are being raised.

The World’s Smallest Museum

Walk up to the Royal Mile from the Grassmarket and you’d be forgiven for not realising that you’ve just walked past two unique things in Edinburgh.

First off, the World’s Smallest Museum, which is actually the shop and booking office for the Cadies & Witchery Tour.

Second, is the fact that you’ll have just walked past one of the smallest relics relating to William Burke and that a calling card case made from his skin.

Yep, another macabre artefact for you to admire and I can’t tell you how fabulous it is.

Burke’s Skin Calling Card Case

Souvenirs from the scene of execution on the Lawnmarket and from the dissection itself certainly occurred as far as William Burke was concerned.

Not only was rope sold by the hangman, but as we’ve seen, books bound in his skin, a practice called anthropodermic bibliopegy were made, as well as smaller ‘offshoots’ of the practice.

I travelled to Edinburgh once to specifically see the calling card case and I’m delighted that I made the effort as I got talking to one of the guides here, Robin, and I couldn’t believe it when he took the case out of the cabinet for me and that I got to touch it!

Trust me when I say it was tiny and in every way perfect. It was almost as if it was covering a smaller template made of stiff card inside and it fit snug into Robin’s palm.

Even if you don’t book a tour, you’re still welcome to visit and see the World’s Smallest Museum with one of the most macabre relics in it to date.

Burke’s Brain In a Jar

A teeny tiny portion of Burke’s brain survives in an anatomical specimen jar at The Science Museum in London.

The note accompanying the specimen reads:

presented by the doctor who used Burke’s body for anatomical purposes, in a sealed glass tube 3” long

I understand that this particular exhibit is not currently on display so if you are hoping to head to The Science Museum to see it, please do get in touch with them beforehand to check if you can.

The Displaying of Burke’s Skeleton

The Skeleton of William Burke is on display as it was part of the sentence passed down to him for murder. The 1752 Murder Act stated that the body of a murderer, once executed should ‘in no case suffer to be buried’. Additional punishment of the corpse could also result in either gibbeting or dissection.

As I mentioned above, the additional punishment of the corpse was left to the Lord Justice-Clerk’s discretion and on summing up Burke’s sentence, in addition to being anatomised, he also uttered these famous words:

‘….if it is ever customary to preserve skeletons, yours will be preserved, in order that prosperity may keep in remembrance your atrocious crimes.

And so it was that Burke was hanged, dissected and to this day hangs in a glass display case in the Anatomical Museum, Teviot Place, Edinburgh. His crimes are certainly remembered.

What Happened To William Hare?

William Hare turned King’s Evidence and escaped the hangman’s noose. He was given immunity on 1st December 1828 after agreeing to give details about the murder of their last victim, Mary Docherty. Hare was allowed to go free and the last confirmed sighting of him was on a coach bound for Dumfries.

The evidence that surrounds the last whereabouts of one of Scotland’s most prolific murderers is pretty much nonexistent, hence all the rumours that are flying about on the internet and in books today.

The most common belief is that Hare was a blind beggar on the streets of London. Such a well-known figure was Hare that mothers are said to have threatened their naughty children if they didn’t behave. Hare will come and get you they said. Eek they said…

I’ve written a more in-depth blog post about What Happened to William Hare if you’re interested in reading all the theories out there, but if you prefer to just get the gist, then please read on.

William Hare is Recognised In Dumfries

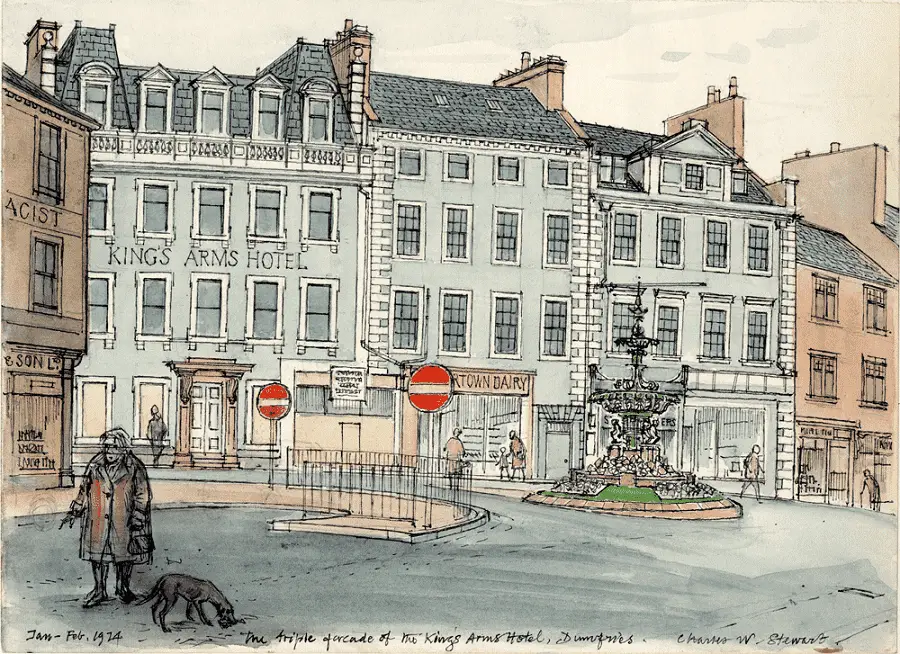

Things started to unravel after William Hare, going under the disguise of a ‘Mr Black’ was recognized by Erskine Douglas Sandford, a junior counsel representing the family of Jamie Wilson, better known as ‘Daft Jamie’.

By the time Hare had arrived at his destination of Dumfries, a mob was already waiting for him and he was quickly escorted through to the back of the Kings Arms pub in the High Street.

After an undercover escape in the early hours of the morning, the last confirmed sighting of Hare was when he was seen on the Annan Road on his way out of town. From here, folklore and speculation take over.

The most popular story is the one mentioned above about Hare being a blind beggar on the streets of London, but other stories are starting to take hold and generate their own interest.

I doubt we’ll never know for certain as to what actually happened to William Hare.

The Burke And Hare Rhyme

Many people know the famous rhyme associated with Burke and Hare. Here it is in its entirety.

Up the close and doon the stair;

But and ben wi’ Burke and Hare.

Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief,

Knox the boy who buys the beef.

A short six-line rhyme, no doubt chanted by children and adults alike on the streets of Edinburgh sums up their crimes perfectly.

Although this may be the most famous of the Burke and Hare rhymes, there were many more printed and sung both during and after the trial.

Finally, this YouTube clip doesn’t cover the rhyme itself, but instead covers the crimes of the two men and is quite a catchy little thing. It’s a little over 2.30 mins long if you fancy tapping your feet for a little bit.

My favourite song about Burke and Hare is actually the title song from the 1972 film by Kenneth Shipman. Now this really will stay in your head all day, so fair warning dear reader. You can find it here, sung by The Scaffold.

I doubt we’ll ever get to the end of asking questions about Burke and Hare, but I hope I’ve been able to answer a few of yours here.

Burke & Hare Recommended Reads

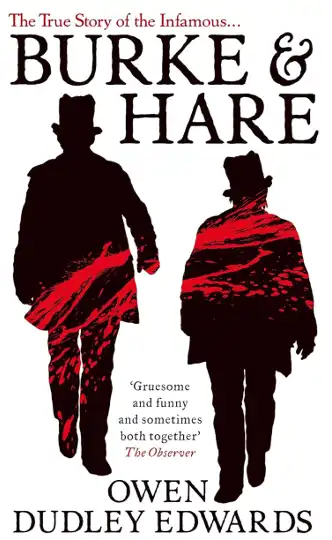

There’s a whole raft of books written about Burke and Hare, but the one I recommend reading is actually a book that I hated when I first picked it up.

That book is by the renowned Burke and Hare historian, Owen Dudley Edwards and it’s the one in the link at the end of this post.

It took me a while to get into Edwards’ style, I found him a bit off the wall at first, but now I have to say, I quite enjoy the read.

Edwards includes things in this book that others don’t which is why I think I enjoy reading it. That said don’t be put off by the other books I’ve mentioned above, my second favourite, and equally as thorough is Brian Bailey’s ‘Burke and Hare: The Year of the Ghouls’.

Burke & Hare

If you pick just one book on Burke & Hare, let it be this one! After originally hating it, I now love it.

Edwards shares bits about the murders that other authors seem to gloss over. Just fabulous!