The Tedious Job Of Oakum Picking In A Victorian Prison

If you’re doing any research into criminal ancestors, or even Victorian prisoners in general and the time they spent in prison, chances are you’ll have heard about oakum picking, sometimes known as rope picking.

While I was researching the infamous body snatcher Joseph Naples – whose background could be a website all of its own- I came across a fantastic account in 1802 where he’d escaped after making a ladder from oakum and scaling the prison wall!

But although I already knew a little about oakum picking, I’d never really gone into any depth as to what it actually was and what happened to it once it was picked.

As a general rule, if your ancestor was sentenced to hard labour then they would have either picked oakum or spent time on the treadmill. Oakum picking was the teasing apart the fibres of old ship rigging, or ‘junk’, on average 2ft every day, which was then sold back to shipbuilders and used as wadding/caulking between the wooden planks, making it watertight.

In this post, I’ve taken a closer look at this notorious form of hard labour which would make your fingers bleed and your back break.

Table of Contents

- What Was Oakum Picking?

- How Did You Pick Oakum As A Victorian Prisoner?

- Where Did People Pick Oakum?

- The Method Of Picking Oakum

- How Much Oakum Did Victorian Prisoners Have To Pick Each Day?

- What Was Oakum Used For?

- Did Women And Children Pick Oakum In Victorian Prisons

- Oakum Picking In The Victorian Workhouse

What Was Oakum Picking?

Oakum picking, or rope picking, may be one of the most recognisable forms of hard labour found in Victorian prisons alongside the dreaded treadmill, but what exactly was it?

Oakum picking was a way of utilising old ship rigging or ‘junk’ and putting it back into good use. Lengths of rope, which were on average about 2ft in length, just over half a meter, were hand teased into their original fibres and sold back to the shipbuilding yards. Here the oakum would subsequently be mixed with tar and the fibres used to plug any gaps between the boards on the ship making them watertight.

Not only did this help to generate revenue for the prison, but it’s also where the phrase ‘money for old rope’ comes from.

It is a recognised form of hard labour for Victorian prisoners but inmates in Britain’s workhouses could also be found assigned the task as a way of paying for their keep as we’ll see below.

How Did You Pick Oakum As A Victorian Prisoner?

Before lengths of rope were dished out to the prisoners, they would have been cut up into sections and then beaten with a mallet or hammer in order to remove any encrusted tar from the outside.

Piles of ‘junk’ were then placed at the feet of each prisoner, be that in their cell under the ‘Separate System’ of the 1830s and 1840s or in an oakum picking room like that at Coldbath Fields House of Correction and carried out in complete silence.

Inmates were expected to pick apart the whole pile of rope before the day was through.

Where Did People Pick Oakum?

In Aylesbury prison for example[1] prisoners spent most of the day confined away in their cells, having been given the exact quantity of rope to be picked in the morning.

A similar situation was played out at Wandsworth prison. In Jill Evans book ‘A History of Gloucester Prison’ she notes that twenty-three men were set to picking oakum in their cells under the Separate System.

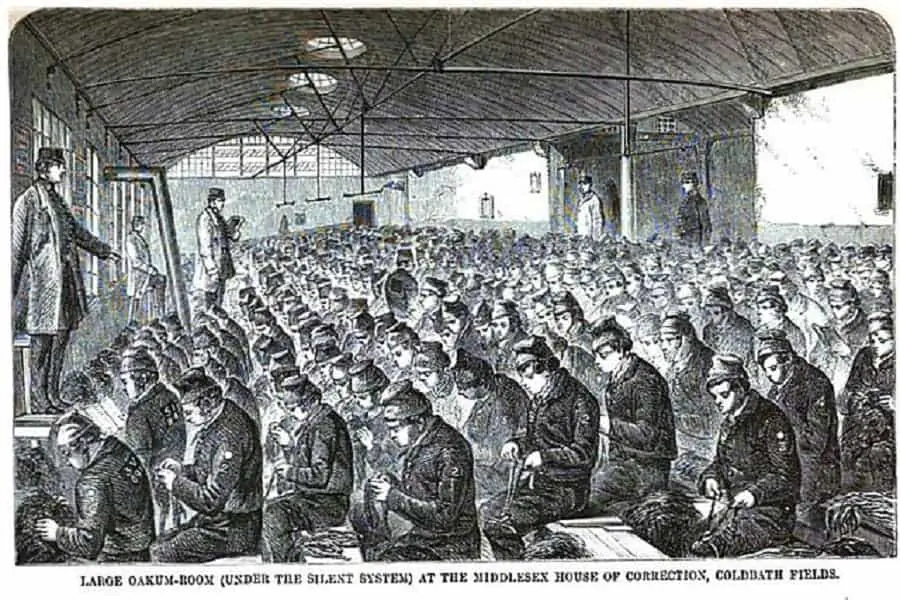

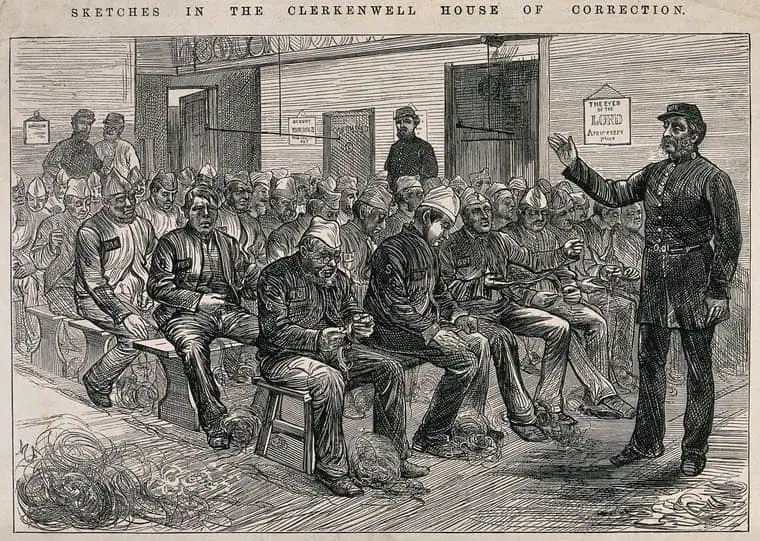

In contrast, prisoners at Coldbath Fields were in the enviable position of being seated in a large building dedicated to the task. The prison boasted three separate rooms for picking oakum, one in the misdemeanour prison, Henry Mayhew, the social reformer notes, and two in the felons’ prison.

During Mayhew’s visit to the prison in 1862[2] he spent some time in one of the rooms in the felons’ prison which held up to 500 men, all squashed into eleven rows.

By all accounts, the rooms for oakum picking at Coldbath Fields, which Mayhew describes as being nearly as long as ‘sheds seen at a railway terminus’, were unique in that their walls were decorated with scripture.

The Method Of Picking Oakum

But just how did you pick apart this material that turned your fingers black and left them bleeding after only a few hours work?

First, the thicker strands of rope would have been untwisted by hand to separate the individual sections and make them more pliable. These strands would then have been rolled back and forth over the knee, using the palm of the hand until the strands were separated.

To help get a better understanding, if you whizz past the stone pickers, rat catchers and child chimney sweep in this Youtube video below called The Worst Jobs in History you can see some oakum picking in action at about 36:12.

The clip relates to picking oakum in the workhouse, but the principles are the same.

For the rope to be able to be reused, each strand had to be completely separated, and so it is at this stage that the ends of these larger strands would be placed in the bend of an iron hook, as Mayhew describes:

Then the strand is further unravelled by placing it in the bend of a hook fastened to the knees, and sawing it smartly to and fro, which soon removes the tar and grates the fibres apart. In this condition, all that remains to be done is to loosen the hemp by pulling it out like cotton wool, when the process is completed’

How Much Oakum Did Victorian Prisoners Have To Pick Each Day?

Men, women and children would employ nimble fingers to pick apart blackened rope for periods of up to 12 hours a day.

By the time Mayew was making his observations in 1862, defined daily quantities of oakum that had to be picked by each individual were being set out.

If these weren’t met then further punishments could be received. At Tothill Fields House Of Correction, which opened its gates in 1834 and which was being used solely for female prisoners and juvenile male prisoners by 1850, the following quantities of oakum had to be produced:

In 1861, a year before Mayhew made his study of London’s prisons, Tothill Fields closed its doors to young male prisoners and they instead were sent to Coldbath Fields House of Correction, also known as the Middlesex House of Correction or Clerkenwell Gaol.

The quantity of oakum that had to be picked here was the same as it had been for a boy over 16 years old at Tothill Fields – that is 2lb (910g) per day, unless you’d been sentenced to imprisonment which included hard labour and then the quantity shot up to between 3lb – 6lb (1.4-2.7kg) per day.

The rope was then sold back to the dockyards for £4 10s per hundredweight. Prisoners who were undergoing naval punishment were also subjected to the mind-numbing, finger-splitting task of picking oakum.

For these Victorian prisoners, their daily quota was much smaller than that of someone in a brick-and-mortar establishment. An expectation of 1lb (450g) was expected from these prisoners.

What Was Oakum Used For?

Oakum’s main use was for repurposing in shipbuilding, being utilised in making waterproof caulking/wadding when mixed with tar, but it also had other uses, some perhaps which may not immediately spring to mind.

Other basics for this recycled resource included making matting and bandaging, but in 1885 W.T.Stead – editor of the Pall Mall Gazette and one of the most controversial editors of his day – used oakum in a far more ingenious manner.

Alternative Uses For Oakum

As Stead was picking up his prison uniform on his arrival at Coldbath Fields, he, along with all the other new inmates were having a few issues when sifting through the assortment of garments on offer. Nothing seemed to fit – it was either too big or too small.

When the time came for Stead to choose his shoes, he settled on a mismatched pair that after two day of excruciating pinching because they were too small, he was forced to swap for a larger size. So big was this second pair that he was forced to stuff oakum into them whenever he went to exercise.

Presumably, removing the oakum and adding this back into his daily production quota at the end of each day.

Another use for oakum, and one which was not only frowned upon by prison wardens but one which seemed remarkably difficult to pull off was to use it as a pillow.

During Stead’s confinement in Coldbath Fields, he spent two days in a cell which to his account he ‘enjoyed … very much’. Immensely pleased with the additional warmth that this temporary cell provided, the editor was somewhat disappointed to hear that he was to spend the next few nights without a mattress, to which he suggests oakum as a pillow.

You can read a full account of Stead and his time in Coldbath Fields prison on attackingthedevil.co.uk[3]

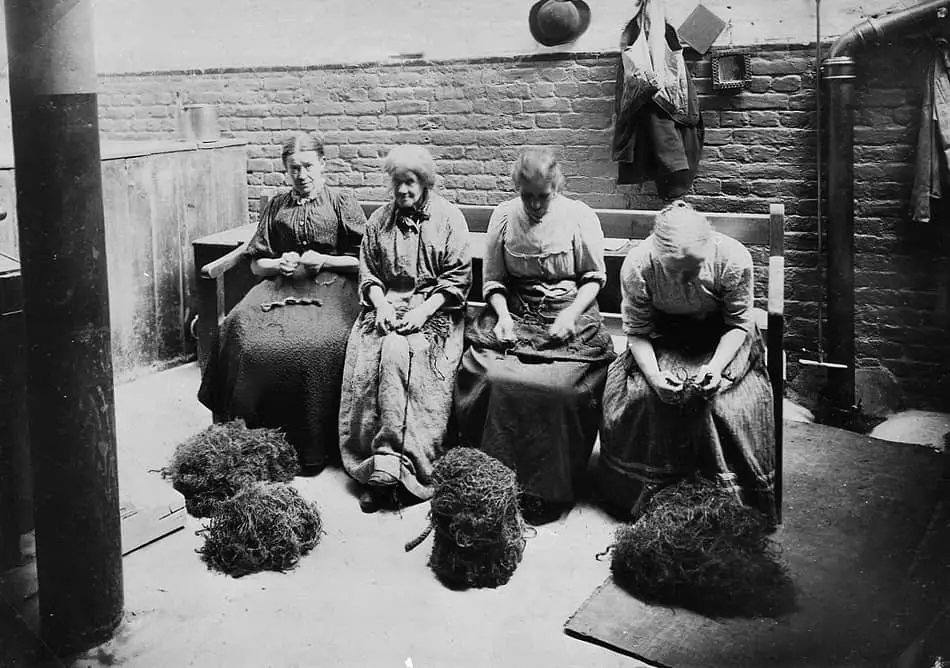

Did Women And Children Pick Oakum In Victorian Prisons

As a general rule, women in Victorian prisons were either employed in the laundry or used to clean the prison itself. Those that were unable to carry out any physical work would often be sent to picking oakum.

In Gloucester prison, Evans notes that women were employed in ‘washing, needlework and cleaning the prison’ while during Mayhew’s visit to the female prison at Brixton in 1862, he notes that work was predominantly in the laundry, for it is here that the washing of Victorian prison uniforms is carried out for the 1858 prisoners across Pentonville, Millbank and Brixton itself.

I doubt the ladies would have had any time or energy to do anything else if I’m honest!

We’ve already seen the quantities of oakum that the children at Tothill Fields House of Correction had to unpick on a daily basis – between 1lb and 2lb depending on their age and sex – but was Tothill a typical example?

I’ve been unable to find anything concrete during my searching on the internet for this post, so if you do happen to know, I’d love to hear from you. Children would be put to picking oakum for up to five hours a day in some instances, their small fingers bleeding and sore by the end of it.

Oakum Picking In The Victorian Workhouse

Life in the workhouse was tough, most people know this if they’ve ever watched a documentary or read a book on the subject, but as I was bringing my research to an end for this post, I was quite surprised at just how tough the conditions were.

Those inmates capable of carrying out work were required to do so after the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. This meant that they were now contributing to their board and lodge.

Just as it was for prisons, the oakum would be sold back to the shipbuilders once it had been picked apart, the money generated going back into the individual workhouse.

Although the majority of work for the women still included time in the laundry, those that were unable to work were set to the task of picking oakum to help pay their way.

On the website for the Powys Digital History Project[4] which covers the history of eighteen communities in the Powys region in Wales, rules regarding the quantities of oakum to be picked in all workhouses after 1882 are given in much more detail:

As regards males, for each entire day of detention The breaking of seven cwt of scones, or the picking of 4lb of unbeaten or 8lb of beaten oakum or nine hours work of digging or pumping or cutting of wood or grinding corn. As regards females, for each entire day of detention The picking of 2lb of unbeaten oakum or 4lb of beaten oakum, or nine hours work in washing, scrubbing and cleaning, or needlework.

It’s a small wonder that people feared the workhouse, with regimes much harder than those found in the country’s prisons.

Taking Things Further

[1] The information for Aylesbury prison was obtained from the Center for Buckinghamshire Studies website.

[2] If you are researching your criminal ancestors and you discovered that they were in prison in London, then the best FREE resource available to you has to be ‘The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of Prison Life’ by Henry Mayhew & John Binny, 1862. The report gives perhaps the most detailed description of life inside not only the criminal prisons of London but also the prison hulks at that time.

[3] I highly recommend wasting a few hours on the fabulous website attackingthedevil.co.uk which covers everything you need to know about W. T. Stead, editor of The Pall Mall Gazette. I can guarantee that you’ll get lost for hours on this fabulous resource.

[4] The Powys Digital History Project is a resource for primary school teachers which I thought may be of interest to you. It was the only place online that I could find any indication as to the quantities of oakum picked with the workhouse.

My area of interest or knowledge isn’t in the workhouse poor and so I have just looked at this topic in regards to oakum picking, if you’re interested in looking further into the lives of your ancestors who spent time in the workhouse then Peter Higginbotham’s site workhouses.org.uk is a great starting point for the subject.