Famous Death Masks: The Haunting Faces of History’s Most Noted Figures

This site uses affiliate links to sites, including Amazon. If you decide to make a purchase through any links, I’ll earn a small commission from the sale at no extra cost to you. Please read my Disclosure Policy for further information.

There’s a row of death masks displayed way above head height on a wall in what is reputed to be one of the ‘Most Haunted Pubs in York’, The Golden Fleece.

I’m not sure who they are, I’m not sure if anyone knows. Are they even famous?

Half of me thinks they’re casts of staff members who’ve seen some of the ghosts here and swiftly left.

Who knows?

But one thing I do know for sure is that these masks, as well as the death masks in Scotland’s National Gallery, intrigue me. There’s something profound about these plaster faces that keeps me rooted to the spot, and I know I’m not the only one.

And so, from William Burke’s death mask – actually it’s a life mask but more on that later- in Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh to the story behind one of the world’s most recognisable faces – Resusci Anne – whose face has been kissed by millions, get ready, as we embark on a journey into the fascinating world of famous death masks.

And for fellow death mask enthusiasts, I’ll also share where you can view these macabre treasures in museums in the UK.

Table of Contents

If this sort of dark history interests you, then my newsletter might too. I share historical finds like this — plus historical true crime you won’t see in the history books. You can sign up here.

The Fascination with Death Masks

Death masks have captivated many of us for centuries, serving as a macabre bridge between the living and the dead, preserving the exact facial features of notable historical figures, criminals, and unknown individuals moments after death.

Today they serve as objects of fascination, perhaps a museum piece or a prized possession in a private collection, but that’s not always been the case.

The golden funerary masks of ancient Egypt, the solemn casts of kings, queens, artists, and even unknown victims – death masks were never really meant for museums or collectors.

But our fascination with these things stems back to the Egyptians, when Tutankhamun (or Tutankhamen depending on your spelling) ruled all he could survey and to a time when his legendary golden visage was sealed deep within his burial chamber in Egypt all those centuries ago.

And then something in us shifted and death masks began to have a different value and meaning, making them revered in their own right.

But what made us want to cover the faces of the deceased in cold plaster of Paris and capture their expressions forever in the first place?

What is a Death Mask?

A death mask is an impression of a dead person’s face which is captured either in wax ( a method favoured by the Romans) or liquid plaster soon after they have died.

Death masks capture a likeness, or ‘image’, of the deceased’s facial features before death (decomposition) has altered their appearance.

Serving multiple uses throughout history, death masks – the plaster cast style that we think of today – were widely studied by artists to help create posthumous portraits.

Loved ones kept them as remembrances, and scientists even used them to analyse supposed criminal tendencies through that new pseudoscience called phrenology.

How Do You Make A Death Mask

With the aim of a death mask being to capture the true likeness of the deceased before decomposition took hold, timing was crucial.

Originally performed by physicians, not the artist or sculptor as you might expect, casts were typically taken within an hour or two of death – provided the necessary materials were available.

When Napoleon died, for example, his physicians had a terrible scramble trying to gather materials together to make a mask fearing that his features would be lost before they could gather supplies.

The aim with a death mask is to get a cast taken before bloating distorts the features of the deceased.

Preparation Of The Face

Plaster casts were likely more common than wax molds – a material often used in Roman death masks.

To ensure the plaster could be safely removed, physicians applied a grease – in the 20th century, Vaseline was used, but earlier methods likely relied on animal fats – to the face and hairline, paying special attention to the eyebrows and any facial hair.

This grease not only helped the initial layer of plaster to peel from the face easier at the time of removal, but it also stopped it ripping out the eyebrows or tearing along the hairline when it was removed.

A nasty occurrence that would not only have damaged the face of the corpse but also rendered the cast unusable.

Also aiding removal is the placement of a silk thread along the center of the face, so that the cast, once dried, can be removed in two halves.

Application & Removal of a Death Mask

It wasn’t just a case of pouring liquid plaster over the deceased’s face and waiting till it set. This approach would have failed to capture the fine detail, instead leaving behind a chalky lump resembling run off from a slag heap.

The first layer was the most crucial, as this was the one that captured the features of the deceased.

After greasing the face, the initial layer of plaster was applied using one of two methods:

- Strips of bandages infused with plaster, which were wetted and then layered onto the face.

- Plaster brushed directly onto the skin, covering the hairline, ears, and facial features.

The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, shares a fascinating account written in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1892 about how to take a cast for a life mask.

Although they assure us that the process would have been very similar for a death mask, I have my reservations about the method used.

I can go along with the plaster being laid across the face in the initial phases but the rest, I’m not so sure about. Take a look below, what do you think?

“the plaster was laid carefully upon the nose, mouth, eyes, and forehead in such a way as to avoid disturbing the features; and this being set, the head was pressed into a flat dish containing plaster, where it continued to recline as on a pillow.”

Meanwhile, The Victorian Book of the Dead offers a fascinating 1912 account on making death masks, along with an intriguing detour into Halloween death masks – both well worth a read.

Perhaps death mask techniques had evolved by 1912, as this source makes no mention of dunking a person’s face into a dish of plaster.

The silk thread initially placed on the face is then pulled part way up through the layers of plaster as it sets, before being completely removed just before the plaster hardens.

This technique allows the mask to be removed in two parts, which can then be molded back together after removal.

Removing A Death Mask

The plaster cast, once removed, actually created a mold or negative impression of the face, not the actual death mask itself. It’s probably easiest to think of it like a chocolate mold for an Easter egg.

This mold would then be used to create the death mask.

Grease was applied inside the mold, and liquid plaster of Paris was poured in to form the first layer. Then, burlap or sacking was added to the inside, and more plaster was poured in to fill the mold completely.

Once the plaster dried, the cast was removed, revealing the death mask.

Other materials could be poured into the mold to make the death mask.

Bronze was perhaps the next most popular, with an example being the bronze mask of Bonnie Prince Charlie, displayed in his former bedroom at Castle Menzies.

Why Were Death Masks Used

Death masks were used because they provided the most accurate way to preserve a person’s likeness before photography.

Artists relied on them for posthumous portraits, scientists studied them for facial structure, and even law enforcement found them useful in forensic investigations.

Death masks weren’t just keepsakes of the dead – they had a purpose.

Artists Reference Material

Capturing the true likeness of someone was invaluable to an artist or sculptor. The cast served as a guide for measuring the distance between facial features, studying subtle details, and analyzing nuances like a sunken eye or a prominent, pointy nose.

Portraits or busts would then be crafted from studying the death mask, and examples of these can still be seen today.

Both Edward III, who ruled England in the 14th century and Henry VII of England (1457 – 1509) have a ‘posthumous portrait bust’ or effigies made of them from their death masks.

Funerary Mask

Although not a cast of the deceased’s face in the same way as ‘traditional’ death masks are, the funerary mask, of which Tutenkhamun’s gold stylised mask is perhaps the most famous, was instead a representation of the deceased.

Funerary masks served multiple purposes, primarily preserving the deceased’s features as a tribute and a link to the spirit world. They were believed to help guide the spirit to the afterlife while also offering protection from evil spirits.

It wasn’t only the Egyptians who used such coverings. A collection of beaten or hammered gold masks discovered in the Lambayeque region in northern Peru are thought to be the largest examples of this style of mask yet found – and complete with danglers yes I wondered what these were too at first!)

Fascinating stuff.

But, that’s not where my interest lies and so I’m not going to bumble my way through writing a post about funerary masks – there’s plenty of people who can do it far more justice than I ever could and the links included above should send you down any suitable rabbit holes.

Death Masks & Science

By the 18th century, death masks began to take on a different value and meaning.

Physiognomy, the study of a person’s character and personality using their facial features alone, was on the rise, and along with it, the new pseudoscience, phrenology.

Alongside being cherished as mementos of the dead, death masks were now taken to study facial features in an attempt to uncover the physical traits linked to society’s most notorious criminals, as well as the more rich and influential among us.

Weaved among the death masks of royalty and notable individuals, as we shall see, lie the faces of some of the world’s notorious murderers and criminals.

It’s also during this period that life masks begin to gain popularity, where the ‘artist’s subject’ would endure a few hours trying not to suffocate while they waited for the plaster to harden.

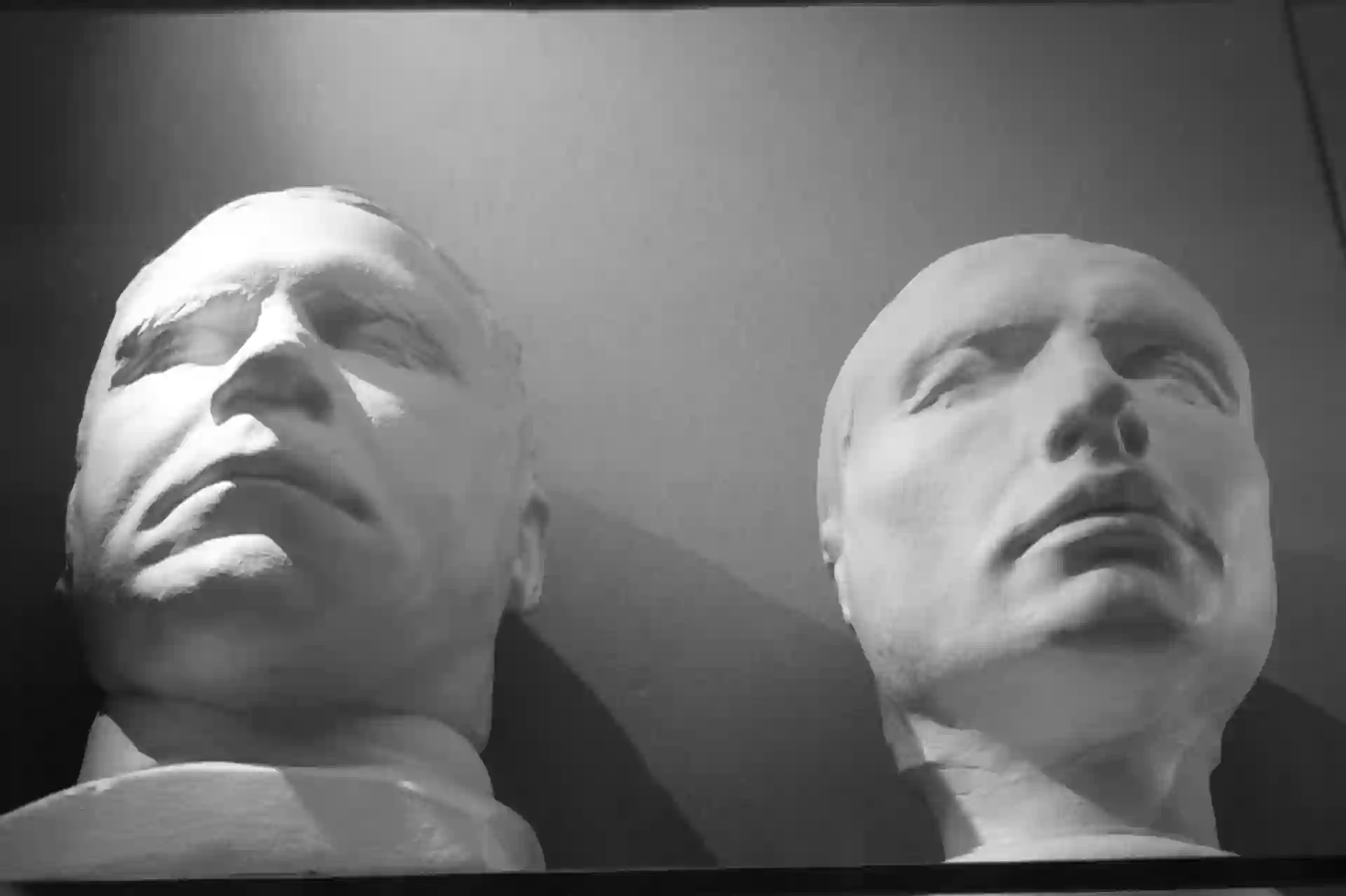

For me, the most notable of these are the life masks of Edinburgh murderers, Burke and Hare.

There’s no doubt that the cast of William Hare is a life mask – for he turned King’s evidence and got away with his life, although no one really knows what happened to William Hare for sure.

But there’s controversy surrounding the ‘death’ mask of William Burke.

Do you agree with the Human Remains conservator at Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh, and friend, Cat Irving that the mask in their collection is a life mask as I do?

Or do you stick with consensus and are adamant that it’s his death mask?

Identification of Unknown corpses

Before the introduction and development of photography, death masks proved vital in the identification of unknown corpses.

Eventually this would be replaced by post-mortem photography, but until then, liquid plaster would be poured over the victims face in an attempt to identify them .

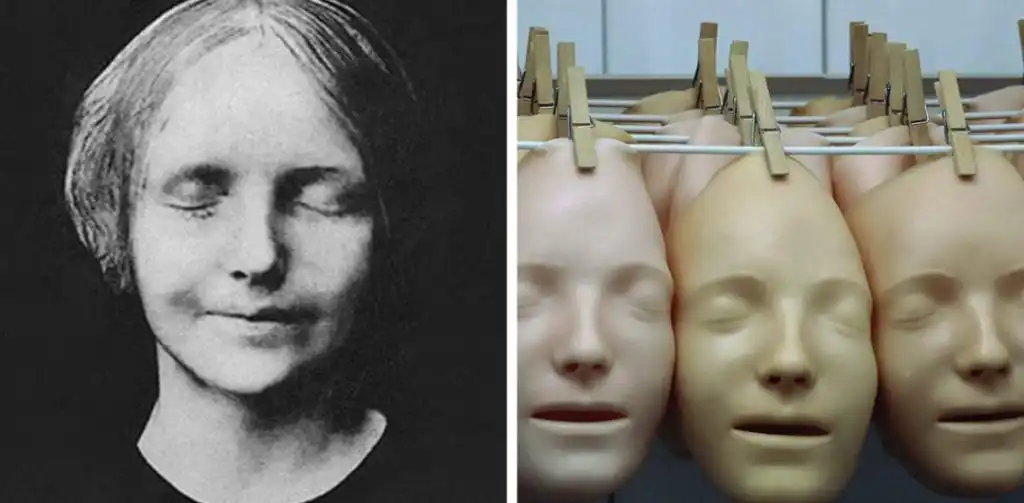

The most famous cast to be made of an unidentified corpse was that of Resusci Anne – L’Inconnue de la Seine, the Unknown Woman of the Seine. You can skip to read her story below here.

(Some) Of The Most Famous Death Masks in History

It would be remiss of me to write a post on death masks without including at least a brief list of the more famous death masks that have survived.

Of course, as with any list, what’s included is a matter of personal preference, so your personal favorite death mask may not be listed below.

So, without further ado, here are some of the most famous death masks in history—perhaps worth ticking off your own bucket list!

The Death Mask Of Tutankhamun

The Egyptian death mask of Tutankamun is arguably one of the most recognisable objects in antiquity.

Perhaps better described as a funerary mask rather than a death mask, this iconic relic lay undisturbed for over 3000 years in Theban Necropolis, Valley of The Kings in Egypt, until Howard Carter discovered it in 1922.

It wouldn’t be until October 1925 – three years later – that Carter and his team opened the innermost of three nested coffins, and disturbed the remains of Tutankhamun – affectionately known to many as ‘King Tut’ – discovering this now infamous Egyptian death mask.

That day Carter noted his discovery:

‘… a very neatly wrapped mummy of the young king, with golden mask of sad but tranquill expression, symbolising Odiris… the mask bears that god’s attributes, the likeness is that of Tut.Ankh.Amen – placid and beautiful, with the same features as we find upon his statues and coffins.’

Symbolising Odiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, Tutenkamum’s mask is also inscribed with a protective spell taken from Chapter 151 the Book of the Dead, engraved in hieroglyphs across its shoulder and back.

The Egyptian Death Mask Of Tutankhamun

The Egyptian death mask of Tutankhamun is one of the most famous death masks in history. Discovered by Howard Carter in 192 in the Valley of the Kings, this gold funerary mask remained hidden for over 3,000 years. Symbolising Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead, it bears an engraved spell from the Book of the Dead across its shoulders. In 2014, a failed restoration made headlines around the world when workers misaligned the mask’s beard.

Image: Creative Commons

The Egyptian death mask made headlines again in August 2014, when a botched restoration hit newstories around the world.

When museum workers accidently knocked off the mask’s beard during cleaning, they stupidly attempted to reattach it using epoxy resin glue.

Their efforts may have gone unnoticed if the beard had been reattached straight, but after six months in place, the disaster was discovered and has since been professionally repaired using beeswax.

Today you can find Tutenkamun’s death mask, along with his straightened beard, in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo

The Slightly Water Damaged Death Mask of Edward III, King of England

Despite suffering significant water damage while firefighters battled The Blitz in 1941, Edward III’s wooden effigy still retains its original plaster mask, cast from his death mask mold.

Carved from a single piece of walnut, the 5ft 10.5in effigy once depicted the king with a beard

Today, it is still the oldest-known death mask in Europe.

You can see Edward III’s death mask for yourself in the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries at Westminster Abbey

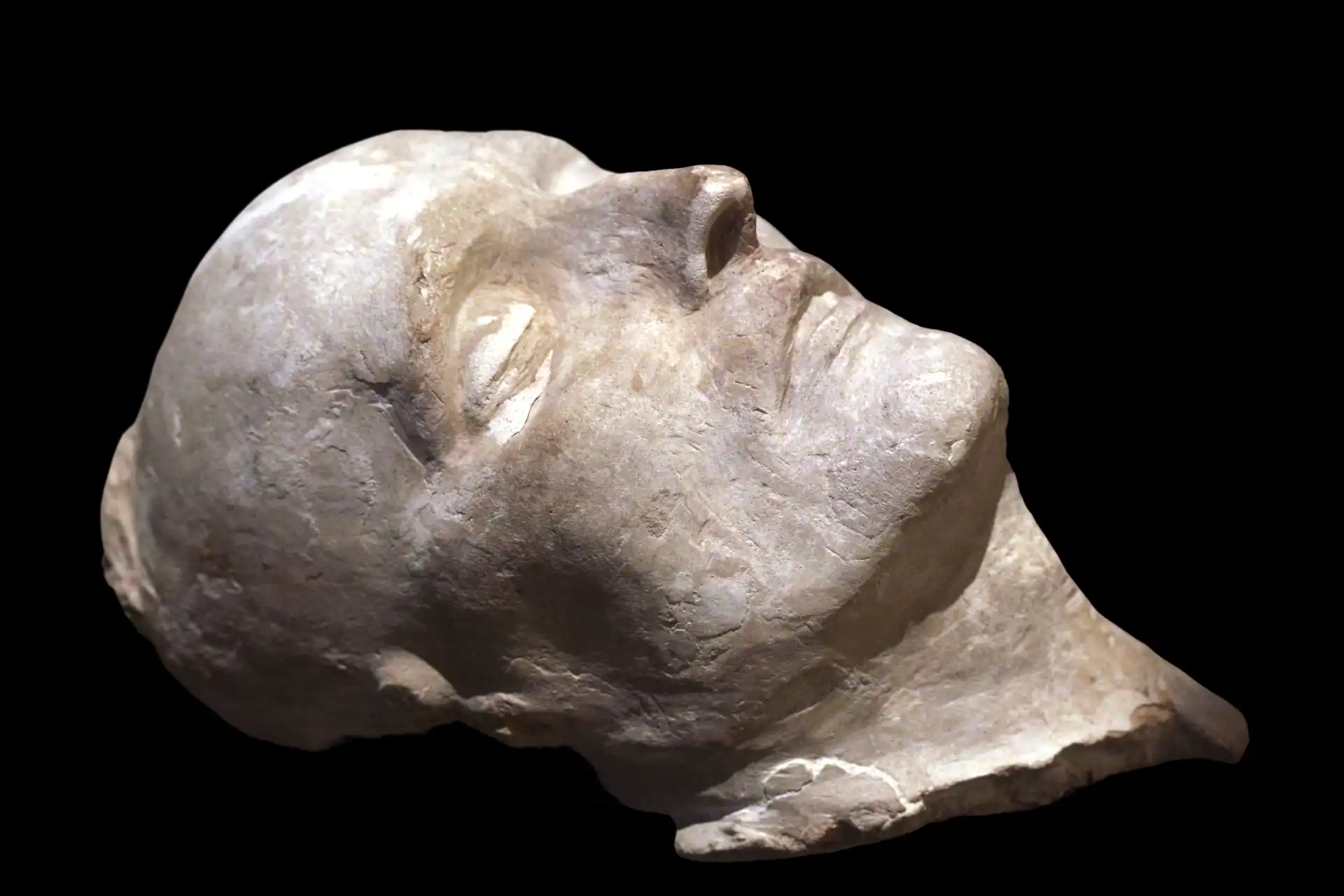

Napoleon’s Death Mask – Or is it

After a brief illness, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte died on May 5, 1821, at the age of 51.

Just one and a half days later, on May 7, 1821, under the sweltering heat of Saint Helena, his death mask was cast.

Due to the number of physicians present at Napoleon’s deathbed, the identity of the person who created the original mask remains uncertain.

Some attribute it to Francis Burton, a British Army surgeon from the 66th Regiment, while others credit François Carlo Antommarchi, Napoleon’s personal physician since 1819.

Antommarchi, who was present at Napoleon’s death, is said to have made several death masks, including some in bronze, from Burton’s original.

Following the theft of parts of Napoleon’s original mask – allegedly by his attendant, Madame Bertrand – only the ears and back of the head remained intact. This led to further copies being made, which soon infiltrated the market.

Of the many replicas that emerged – at least seven are known of – some ended up in private collections, others were rescued from being dumped on waste tips, and a few even found their way into museum exhibits.

Napoleon’s Death Mask ~ Known Examples

- The Antommarchi Mask – The most widely recognised and replicated mask.

- The Arnott Mask – Allegedly made by Dr. Archibald Arnott, thought to have been taken from a wax print.

- The Bertrand Mask – Also known as the Bertrand Malmaison Mask, it bears the inscription August 27, 1821 and is thought to be one of the first copies taken.

- The Guerin Mask – Named after Dr. Francis Burton Guerin, another medical officer present at the time of Napoleon’s death

- The British Museum Mask – Housed in the British Museum, it differs slightly from the others.

- The Malmaison Mask – Kept at Château de Malmaison, the former home of Napoleon and Josephine.

- The Bonaparte Family Mask – Claimed to have remained in the possession of the Bonaparte family

On 19 June 2013, a copy of Napoleon’s death mask, one of the many that are thought to be out there, sold at Bonhams’ Auction House in London for £169,250 – a little over $218,000.

Today, copies of Napoleon’s death mask can be found around the world, although not all are on display to the public.

From bronze death masks in the Auckland Art Gallery, New Zealand and the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art in Clinton, New York to plaster casts in the North Carolina Museum, The British Museum and National Museums, Liverpool, it seems like you can get a bit of Napoleon wherever you are.

Marie Antoinette’s Death Mask

Of all the people to have had their head sliced off by the barbarous guillotine, perhaps the most infamous is Marie Antoinette – the Queen of that immortal phrase ‘let them eat cake’.

Executed for treason on 16 October, 1793, Marie Antoinette’s head was quickly removed by executioner Chalres Henri Sanson, before her body and head were buried in an unmarked grave in Madeline Cemetery, in Paris.

One year later the cemetery was rumored to be full, and its gates were closed on 25 March 1794.

When Madame Tussaud opened her waxwork museum in 1835, she chose Marie Antoinette and her husband, King Louis XVI, as ‘exhibits’ – recreating their features from the death masks she herself had taken of the pair after their execution.

Others death masks that haven’t made it to my list include literary legend Shakespeare, the controversial Oliver Cromwell and the infamous composers Chopin and Beethoven – the list could go on and on.

But perhaps the most macabre and famous death mask of them all is that of the unknown woman who drowned in the Seine, known to the world as Resusci Annie.

Resusci Anne – L’Inconnue de la Seine

In the late 1880s, the body of a woman was found floating in the Seine, the river that runs through the heart of Paris.

Pulled out and laid on a slab in the Paris morgue, the young girl, known the world over today as Resuscitation Annie, was about to make history.

L’Inconnue de la Seine, which translates to ‘the unknown woman of the Seine’ was rumoured to have features so serene that the pathologists working at the Paris morgue that day, felt inspired to create a death mask, capturing her features forever.

Copies of the mask graced the walls of many artists in the 1900, but the unknown girl wouldn’t have become as famous as she has done today without being noticed and used as the inspiration for a first aid training device by Peter Safar and Asmund Laerdal in 1958.

CPR Annie, known here in the UK as Resuscitation Annie has since been used to train countless of medics, first raiders, flight attendants and school children in CPR techniques that has saved millions of lives – something that has resulted in Annie receiving the accolade of ‘the most kissed face in the world’

Questions have since arisen as to the authenticity of the provenance of the unknown woman of the Seine’, with many questioning the mask’s firm features not corresponding with those of a bloated corpse pulled from a river.

Death Masks of Murderers

Although I find death masks interesting, my main interest lies with those cast of murderers and notorious criminals.

While this list could be exhaustive, here are some of the more notable examples that survive, starting with my favourite, that of William Burke.

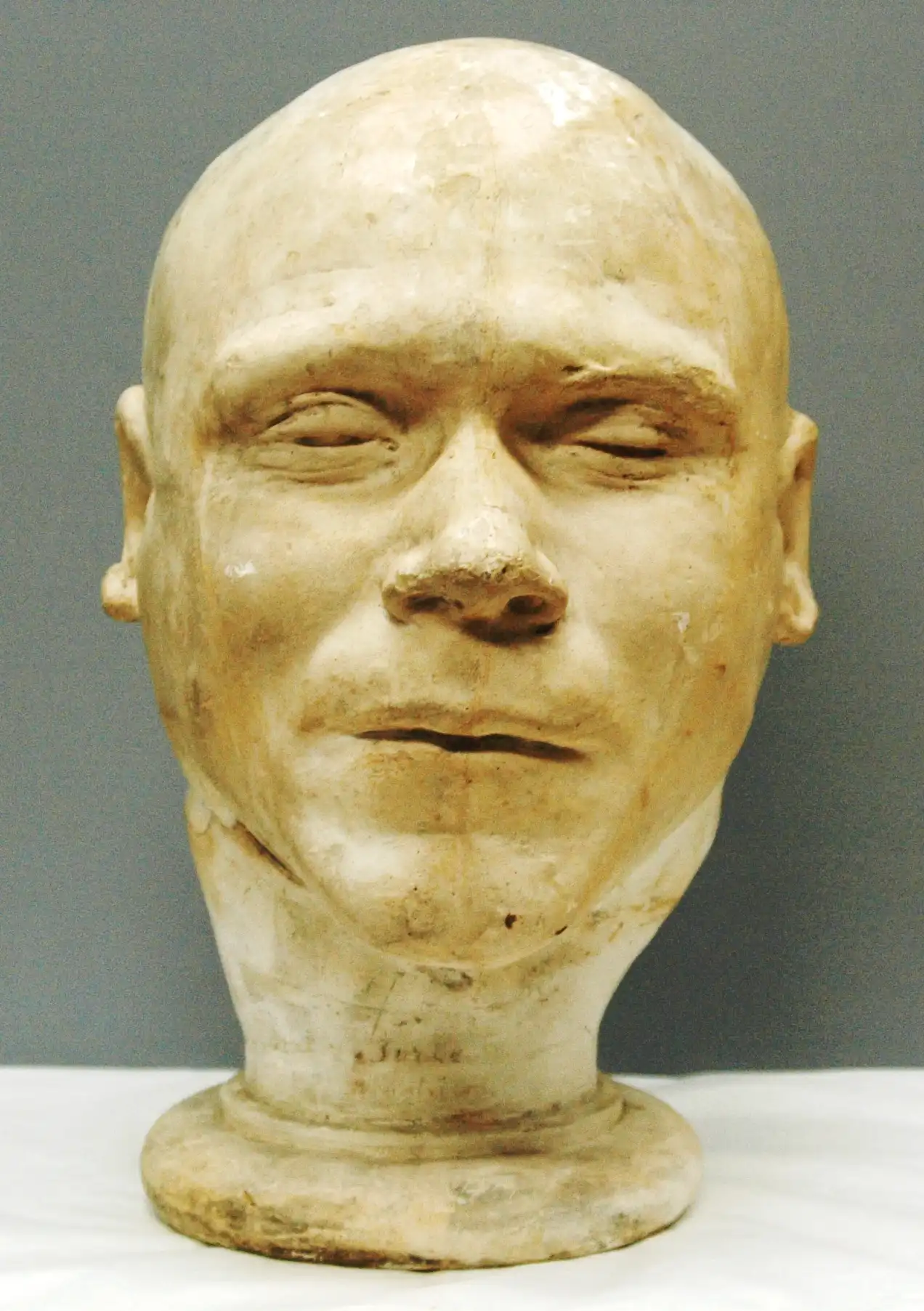

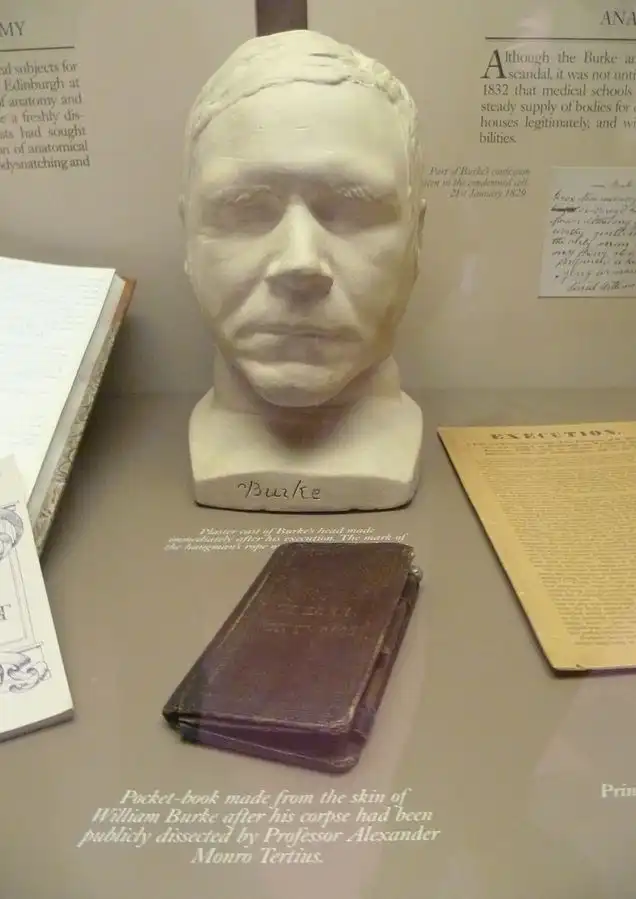

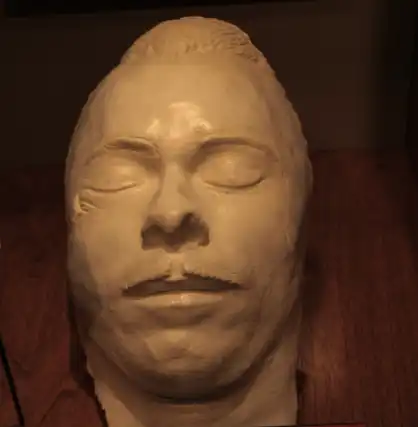

William Burke – Edinburgh Murderer

Ah, the infamous story of Burke and Hare, the Edinburgh serial killers who were finally stopped in their tracks with the killing of Margaret Docherty on All Hallow’s Eve, 1828.

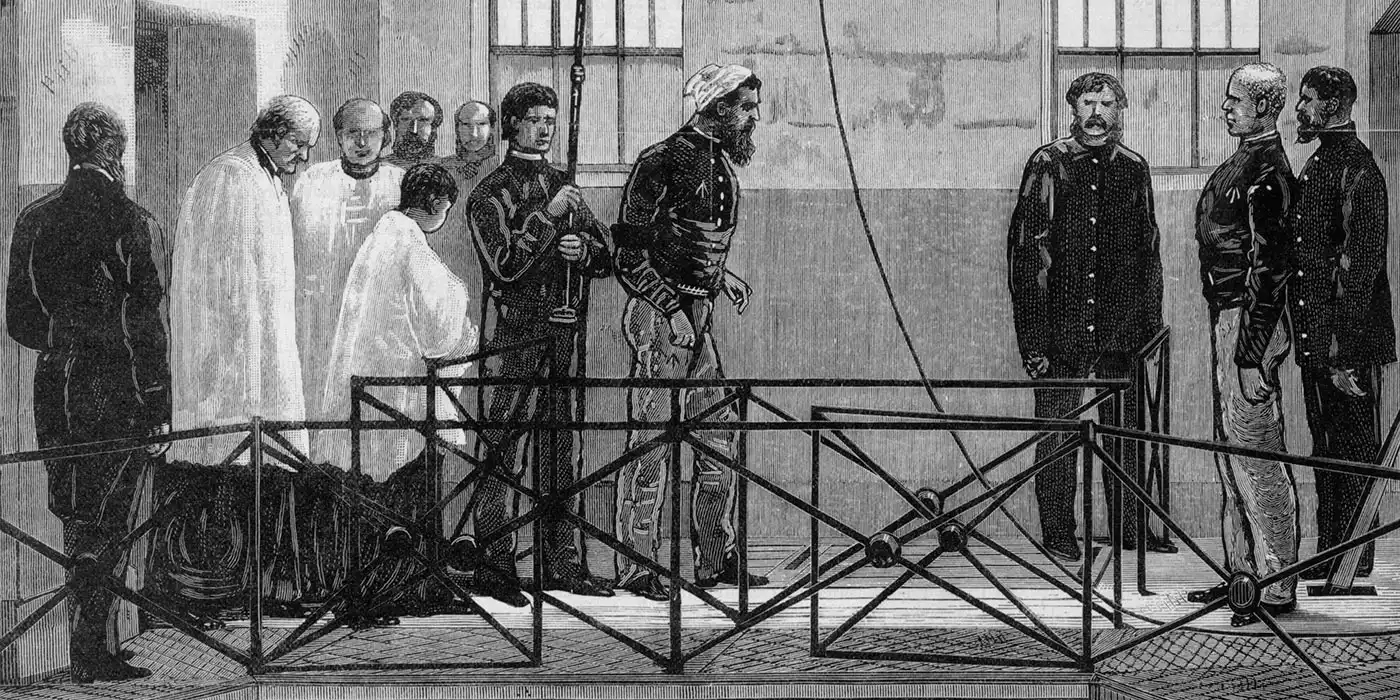

Although Hare turned King’s evidence and was set free, his partner in crime – or one of them anyway for we cannot surely think Knox was innocent – William Burke, was sent to the gallows on 28th January 1829, in front of a crowd of thousands.

Burke was then dissected by Professor Monro at Edinburgh University, a mask taken of his face before distortion could set in and his skeleton set to hang per perpetuity.

The so-called “death mask” of Burke, displayed alongside the infamous pocketbook made from his skin at Surgeons’ Hall in Edinburgh, remains a topic of debate.

Human remains conservator at Surgeons’ Hall, Cat Irving, challenges the notion that it is truly a death mask, pointing out signs of muscle tension in Burke’s face – something that wouldn’t be present post-mortem.

Another compelling argument is the existence of a life mask of Hare. If an impression was taken of him while alive, why wouldn’t the same have been done for Burke?

Ned Kelly – Australian Outlaw

At the age of 25, Ned Kelly, convicted police-murderer, bank robber and outlaw, became the first person born in Victoria, Australia to be hanged.

Gaining notoriety for killing police constables Lonigan and Scanlan, Kelly is said to have worn a suit of bullet proof armour in what was to be his last shootout with police.

After suspending on the end of the hangman’s rope for a full 30 minutes to ensure his extinction, Kelly was cut down and taken to the dead-house across the road from the gallows at Old Melbourne Gaol.

Here, Maximillian Kreitmayer, a waxwork proprietor just like Madame Tussaud, prepared Kelly’s head and created a death mask out of plaster.

Ned Kelly was originally buried in the “old men’s yard” within Old Melbourne Gaol, and a copy of his death mask is now on display at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra.

By 1881, rumors swirled that Kelly’s body had been illegally dissected by medical students. When Old Melbourne Gaol closed in 1929, further speculation arose that workers had stolen bones from a grave marked “E.K.” before the remains of convicted felons were reinterred in a mass grave at Pentridge Prison.

The skull, once believed to be Kelly’s, passed through police departments and anatomy institutes before disappearing in 1978, stolen after an exhibition at Old Melbourne Gaol.

When it resurfaced in 2009, forensic analysis confirmed it was not his. In 2013, Kelly’s actual remains were finally returned to his family and laid to rest in Greta Cemetery – this time encased in concrete to prevent any further theft.

John Dillinger – American Bank Robber

After Anna Sage, a Chicago brothel madam, tipped off the FBI about the whereabouts of America’s “Most Wanted,” John Dillinger was finally tracked down.

On July 22, 1934, outside Chicago’s Biograph Theatre, Dillinger chose to run rather than surrender, pulling out a gun and aiming it at the pursuing officers.

The fatal shot tore through his neck, exiting just beneath his right eye.

Dillinger’s body was put on display at the Cook County Morgue, where hundreds, if not thousands, of people filed past for a glimpse of the infamous gangster – though not all were convinced the police had gotten the right man.

Twelve hours later, dentist Harold May was pouring liquid plaster over Dillinger’s still features.

May’s cast of Dillinger’s features was certainly put to good use. The FBI for one granted the request from individual police officers to take copies of Dillinger’s death mask which was used as a study aid in forensic modeling studies to those attending the FBI Academy.

Even the FBI’s own website acknowledges that this has led to numerous reproductions of Dillinger’s original death mask – many of which are now sold online as supposed authentic pieces.

Where to See Death Masks in the UK

Nothing screams ‘macabre road trip’ like adding a tour of the finest death masks to your bucket list so whether you’re in the UK on holiday or just exploring during a day off or ‘staycation’ then I hope this post has piqued your interest to find out more.

Here’s a few of my favourite museums that have death masks that I’ve visited personally, or are still on my own bucket list to visit in the future.

National Galleries Scotland, Edinburgh

If you’ve not been to the National Gallery in Edinburgh then you are in for a treat. You could easily spend a few hours here, if not more and if you want to head straight to the death masks, then head to the Library & Print Room on Level 1.

It’s here that you’ll find the collection of death masks used by the Edinburgh Phrenology Society.

The masks here are on loan from the Anatomical Museum at the University of Edinburgh after the masks were donated to the University when the Phrenology Museum closed in 1886.

Surgeons’ Hall Museum, Edinburgh

Burke and Hare fans will simply fall over themselves to check out the death (or is it life) mask of William Burke on permanent display at Surgeons’ Hall Museum.

Further treats are in store when you visit, alongside Burke’s life mask (sorry traditionalists, but I’m with the human remains conservator on this one) for there’s a notebook bound in the Skin from Burke’s back too!

If you want more Burke and Hare while in Edinburgh, then you need to visit Teviot Place (only open certain days) and also The World’s Smallest Museum, both of which I discuss in my post The Murderer William Burke: Finding His Skeleton

The British Museum, London

You can’t go wrong at The British Museum if Egyptians are ‘your thing’.

I have spent hours wandering around this fabulous museum, not only in Rooms 62-63, where Egyptian death and the afterlife is displayed in all its glory, but elsewhere too looking at the Living and Dying Gallery in Room 24, Medieval Europe in Room 40 and Room 47, where you can lose yourself in the wonders of Europe between 1800- 1900.

Just be prepared to spend a fortune here, for although the museum is free to get in (one of the reasons it gets so overwhelmingly crowded on rainy days) the shop is phenomenal and you WILL end up buying something for sure.

Westminster Abbey, London

A mix of twenty wooden and wax figures can be seen in glass cases in the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries at Westminster Abbey, London.

It’s here that you’ll see the earliest known surviving examples of death masks of English monarchs, Edward III and Henry VII mentioned earlier .

The George Marshall Medical Museum, Worcester, UK

Discovered quite by chance in the much anticipated but disappointing book 111 Dark Places in England That You Shouldn’t Miss, the George Marshall Medical Museum looks to be a hidden gem in the world of museums.

Free to get in, the website, like the book entry is a little underwhelming but it promises great things I think.